Cooperação entre os democratas-cristãos alemães e os conservadores espanhóis

Distanciando-se da antiga elite franquista, a União Democrata-Cristã alemã (CDU) propôs-se construir uma autêntica democracia cristã na Espanha da transição. Nos anos 90, o partido aproximou-se dos conservadores do Partido Popular (PP).

Pouco parecia unir Adolfo Suárez e Helmut Kohl quando ambos receberam o Prémio Príncipe das Astúrias em Oviedo, em 8 de novembro de 1996. Enquanto o antigo primeiro-ministro espanhol falou das conquistas da democratização no seu discurso de agradecimento, o discurso de Kohl centrou-se inteiramente na integração europeia. Ambos se referiram um ao outro com poucas palavras, embora se considerassem membros da mesma família partidária: a democracia cristã europeia. Ao contrário dos sociais-democratas, a CDU alemã há muito que se distanciava dos seus parceiros espanhóis. Nos anos 60, os governos de Adenauer, Erhard e Kiesinger tinham adoptado uma atitude normalizadora em relação à Espanha de Franco e estavam receptivos ao pedido de adesão do ditador à CEE. No Centro Europeu de Documentação e Informação (CEDI), coordenado por Otto von Habsburg, a CDU mantinha contactos com os políticos do partido do estado. Só a perda do poder em 1969 obrigou os conservadores alemães a recorrer ao trabalho partidário com os democratas-cristãos da oposição para estabelecer contactos internacionais.

No período de transição democrática, a CDU sofreu um duplo naufrágio. Em primeiro lugar, apoiou a Equipa Democrata-Cristã do Estado Espanhol (EDCEE), um conglomerado de cinco partidos democratas-cristãos caracterizado por divergências quanto à direcção geral. Embora o anti-franquismo das figuras centrais da EDCEE, José María Gil-Robles e Joaquín Ruiz-Giménez, fosse apreciado na sede da CDU em Bona, a tendência cada vez mais esquerdista da aliança causava preocupação. Na primavera de 1977, a CDU inclinou-se então para o apoio ao Partido Democrata Cristão (PDC), que tinha sido absorvido pela vitoriosa União do Centro Democrático (UCD) do primeiro-ministro Adolfo Suárez antes das eleições de meados de 1977. Apesar das reservas quanto à presença de antigos franquistas nas fileiras da UCD – a começar pelo próprio primeiro-ministro – os democratas-cristãos alemães cerraram fileiras com o partido, que apoiaram principalmente através de programas educativos da Fundação para o Humanismo e a Democracia (FHD), criada em 1977. Após a derrota eleitoral de 1982, a CDU foi dissolvida devido a disputas internas nas suas alas. A CDU viu-se assim novamente sem parceiro em Espanha.

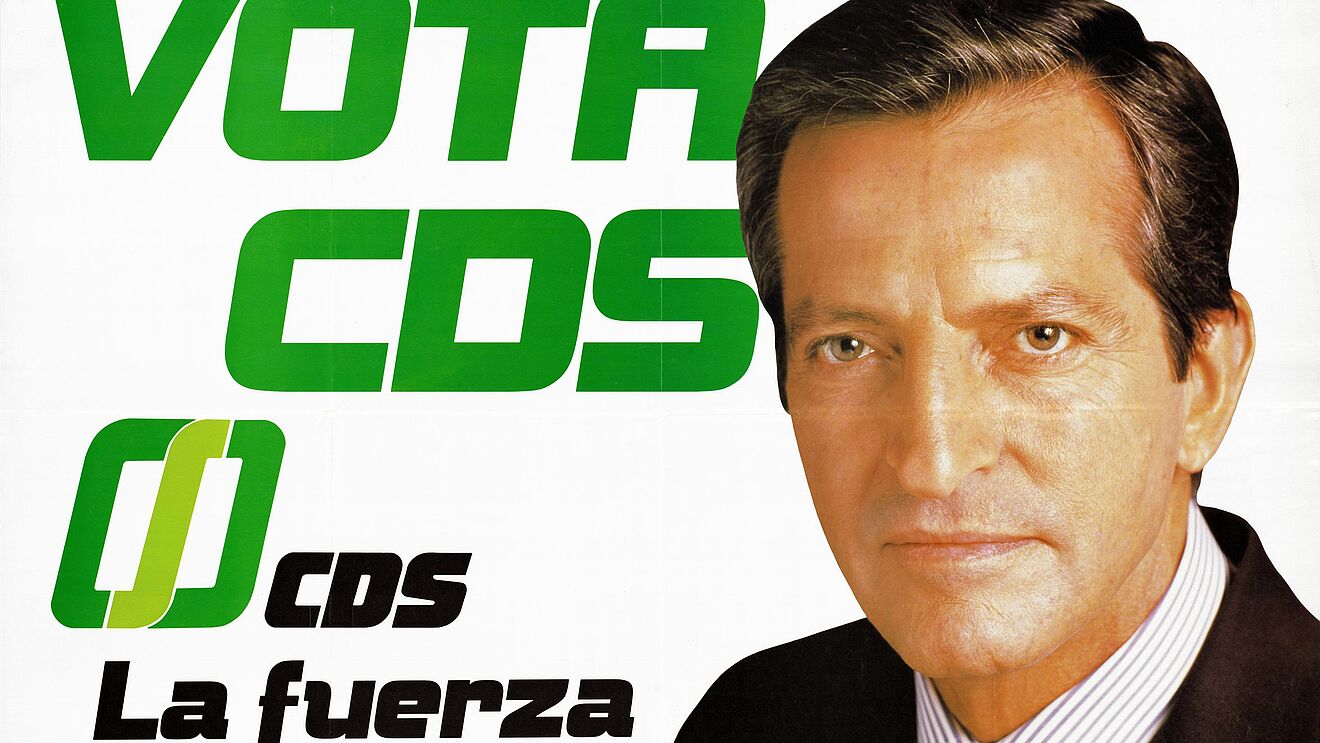

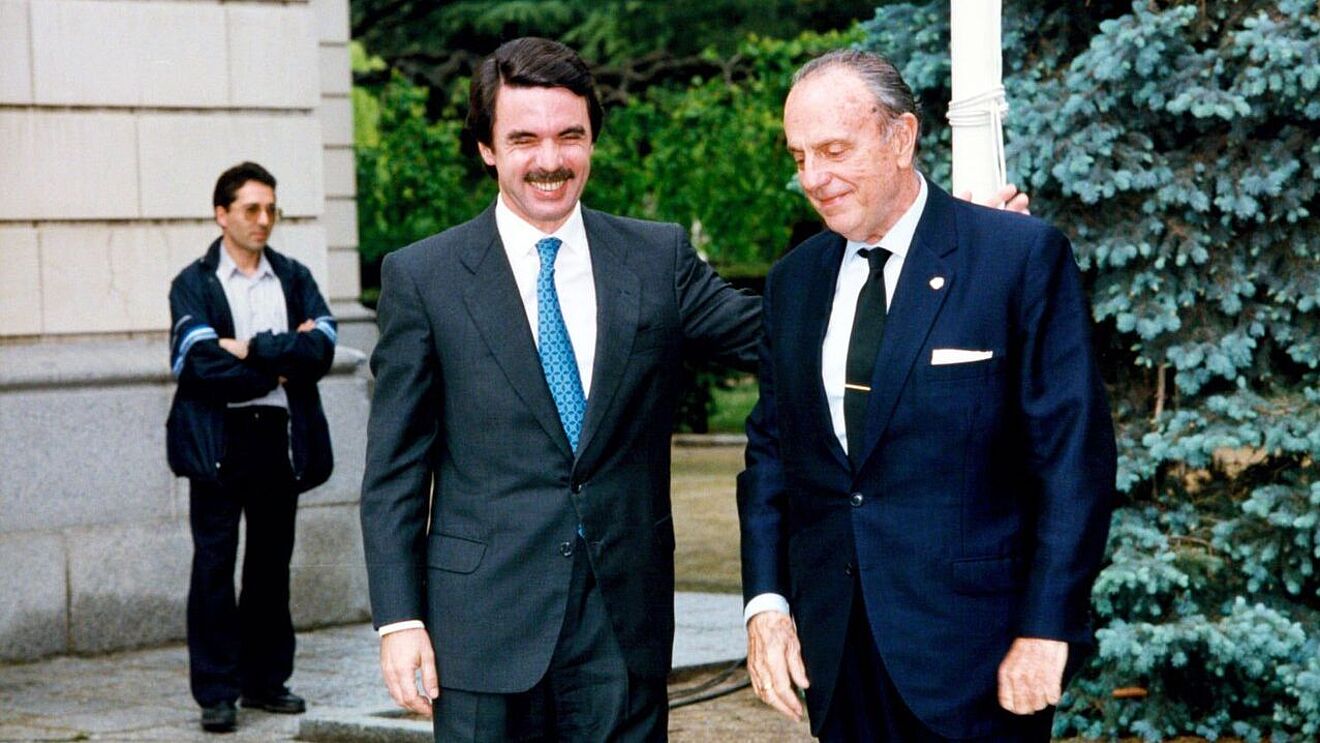

Na década de 1980, porém, o principal problema dos conservadores alemães estava resolvido. Após o colapso da coligação social-liberal, em 1982, a CDU estava de novo à frente do governo. As boas relações entre o chanceler da CDU, Helmut Kohl, e o seu homólogo socialista espanhol, Felipe González, não justificavam um grande investimento na construção da democracia cristã em Espanha. Além disso, o novo Centro Democrático e Social (CDS) do antigo primeiro-ministro Adolfo Suárez falhou redondamente nas eleições parlamentares de 1986 e 1989. O espectro de partidos à direita do centro político aglutinou-se em torno da conservadora Aliança Popular (AP), fundada pelo antigo ministro franquista Manuel Fraga. A inclusão de numerosos antigos membros da UCD, a orientação para o liberalismo económico e a mudança geracional de Fraga para José María Aznar no congresso de 1989 aproximaram a Aliança, agora denominada Partido Popular (PP), da CDU. A colaboração entre a CDU e o PP nos anos 90 foi precedida por um longo período de cooperação entre a AP e o partido irmão bávaro da CDU, a União Social Cristã (CSU). Já em 1976, Franz Josef Strauß tinha visto Fraga como aliado natural dos conservadores alemães.

Kooperation der CDU mit portugiesischen

Christdemokraten und Konservativen

Die Kooperation der CDU mit der portugiesischen Christdemokratie entfaltete trotz einiger Startschwierigkeiten große Wirkung. Zunächst galt es den portugiesischen Partner in die europäische Christdemokratie zu integrieren, woraufhin zahlreiche Projekte in Portugal selbst unterstützt wurden.

Anders als bei der SPD gestaltete sich die Suche der CDU und ihrer parteinahen Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) nach einem geeigneten Kooperationspartner in Portugal deutlich schwieriger. Standen doch gerade konservative Kreise im revolutionären Portugal als „neue Generation“ des alten Regimes unter Generalverdacht. Nach ersten Sondierungsreisen Anfang Mai 1974 schien mit der Demokratischen Volkspartei (PPD) ein geeigneter Partner gefunden zu sein. Diese kultivierte während der Revolution jedoch noch das Selbstverständnis einer sozialdemokratischen Partei, ehe sie sich im postrevolutionären Portugal zu einer klassischen Mitte-Rechts-Partei entwickelte. Folglich lehnte sie die Avancen der CDU und der KAS ab. Nach diesen anfänglichen Misserfolgen rückten zwei neugegründete Parteien in das Zentrum des Interesses: Zum einen die im Mai 1974 gegründete katholische-konservative Partei der Christdemokratie (PDC) und zum anderen das im Juli 1974 gegründete Demokratische und Soziale Zentrum (CDS). Der PDC wurde bis 1976 nicht zu den Wahlen zugelassen und fristete auch danach eine Randexistenz, weshalb schließlich die Wahl auf das CDS fiel. Dieses wies vor allem in den höheren Etagen eine personelle Kontinuität zum Estado Novo auf, wodurch diese Wahl nicht unumstritten war.

„CDS gleich Faschisten, die faschistische Kanaille lebt weiter, Feuer auf das CDS“. Diesen Anfeindungen sah sich das CDS während des ersten Parteikongresses im Januar 1975 ausgesetzt. Lediglich die Anwesenheit zahlreicher Mitglieder der Europäischen Union Christlicher Demokraten (EUCD) – darunter der wichtigste Akteur und gleichzeitig Präsident der EUCD, Kai-Uwe von Hassel – konnten eine weitere Eskalation der Situation vor dem Kristallpalast in Porto verhindern. Die Integration der portugiesischen Christdemokratie in die europäische blieb einstweilen auch das höchste Ziel von Hassels im Verbund mit dem Büro der Auswärtigen Beziehungen der CDU und der KAS. Mit der Aufnahme des CDS als Vollmitglied in die EUCD am 5. Mai 1975 konnte dieses Nahziel auch erreicht werden. Das Durchhaltevermögen des Zentrums und seiner deutschen Unterstützer zahlte sich bereits bei den Wahlen im April 1975 aus, als das CDS 7,6 Prozent der Wählerstimmen auf sich vereinen konnte. Im Folgejahr konnten die Stimmen sogar mehr als verdoppelt werden (15,9 %) und so wurde das CDS noch vor der PCP zur drittstärksten Partei in Portugal. Zahlreiche im Wahlkampf beteiligte CDS-Politiker hatten im Vorfeld an KAS-Seminaren in Sankt Augustin teilgenommen.

„Wir tun mehr als die SPD!“ – dies zumindest behauptete Helmut Kohl 1979. Tatsächlich kam ab 1975 zur anfänglich politisch-moralischen Unterstützung auch eine handfeste finanzielle und politisch-fachliche hinzu. Der Grundstein für das finanziell umfangreichste Projekt der KAS in Portugal, das Institut für Demokratie und Freiheit (IDL), wurde am 6. Oktober 1975 gelegt. Das Institut sammelte in seinem Umfeld die Parteiprominenz des CDS und sorgte für die Ausbildung des politischen Nachwuchses. So entsprach das IDL 1979 auch dem Wunsch, die Föderation der christdemokratischen Arbeiter (FTDC) im Verbund mit der KAS zu gründen, um einen christdemokratischen Beitrag zur Gewerkschaftsbewegung zu leisten. Noch im selben Jahr wurde ein weiteres kommunalpolitisches Institut, das Institut Fontes Pereira de Melo (IFPM), für bildungspolitische Zwecke gegründet. Insgesamt sollte die Zusammenarbeit der KAS mit dem IDL und dem IPFM über 18 Jahre andauern.