A Guerra Civil de Espanha (1936-1939)

Nenhum acontecimento marcou tanto a história de Espanha como os três anos de guerra civil. Os efeitos tardios deste conflito, que dividiu a sociedade em dois campos - nacional e republicano e, mais tarde, vencedores e vencidos - ainda hoje se fazem sentir.

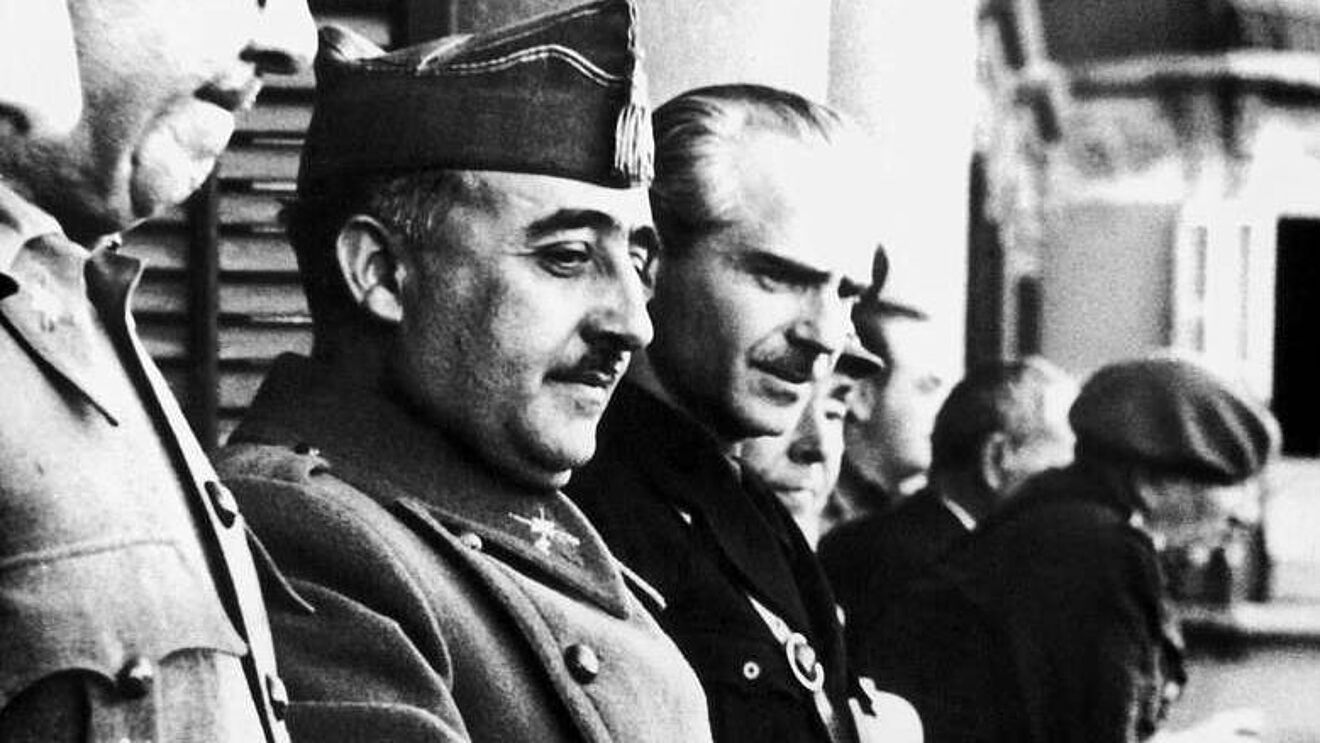

"Espanhóis! [...] A Nação chama-vos para a sua defesa." Com estas palavras, o general Francisco Franco Bahamonde apelou a um golpe de Estado contra a República Espanhola em 18 de julho de 1936. Franco, um militar condecorado e influente, que fez o seu nome na guerra hispano-marroquina (1921-1926), foi um dos últimos a aderir ao golpe contra o governo democraticamente eleito. Dez anos antes, a Espanha já tinha estado sob o domínio de um ditador militar, o General Primo de Rivera. Após o derrube de Primo em 1931, o rei espanhol Afonso XIII foi também obrigado a fugir, pois tinha-o apoiado politicamente. Na Segunda República, proclamada em 14 de Abril de 1931, as forças socialistas e reformistas tomaram rapidamente o poder, esforçando-se por ultrapassar o atraso da Espanha em relação à Europa Central moderna. Os quatro projectos centrais dos governos republicanos - reforma agrária, separação do Estado e da Igreja, redução do corpo de oficiais, autonomia da Catalunha e do País Basco - provocaram o desprezo das elites tradicionais.

Neste clima de polarização social, o exército voltou a tomar o poder. O que foi planeado como um golpe rápido transformou-se numa longa e exaustiva guerra civil em que a Espanha sangrou literalmente até à morte. Enquanto as cidades centrais e os centros industriais como Madrid, Barcelona e Bilbau, bem como grande parte do sul e do leste, permaneceram inicialmente sob o controlo da República, os golpistas venceram na Galiza, no norte de Castela, nas Ilhas Baleares e nas Ilhas Canárias. Unidades irregulares de socialistas, comunistas, anarquistas e progressistas burgueses lutaram frequentemente ao lado da República. Os conservadores, os nacionalistas, os católicos devotos, os monárquicos e o partido fascista Falange juntaram-se ao golpe militar. Assim, um conflito de interesses entre a direcção política civil e os militares transformou-se numa "guerra fratricida", em que as ideias de uma Espanha progressista, igualitária, secularizada e autonomista se confrontaram com a concepção da "Espanha eterna" da fé católica, da unidade territorial e da hegemonia da monarquia, da Igreja e do exército.

A Guerra Civil de Espanha tornou-se um campo de batalha para as ideologias de uma Europa de extremos. Os golpistas foram apoiados desde o início pela Itália fascista e pela Alemanha nazi. Os aviões alemães JU 52, por exemplo, ajudaram a transportar as tropas do exército africano golpista de Marrocos através do Estreito de Gibraltar. As esquadrilhas da Legion Condor alemã e da Aviazione Legionaria italiana bombardearam Gernika, a cidade sagrada do País Basco, destruindo-a quase por completo. A República Espanhola, por seu lado, recebeu ajuda da União Soviética e pagou as armas, as munições e os tanques T-26 com ouro do Banco de Espanha. A Internacional Comunista mobilizou cerca de 50.000 combatentes convictos de toda a Europa para as Brigadas Internacionais. As democracias liberais do Ocidente (França, Grã-Bretanha e Estados Unidos), por seu lado, optaram por uma política de não-intervenção, contribuindo assim indirectamente para a vitória dos militares nacionalistas do general Franco. Após três anos, que causaram cerca de 300.000 mortos e 500.000 refugiados políticos, a guerra terminou a 1 de Abril de 1939.

Militärputsch und Werden des Estado Novo (1926-1933)

Nach sechzehn Jahren scheiterte der erste Versuch in Portugal, das Land auf einen demokratischen Weg zu führen. Die Instabilität der Ersten Republik (1910-1926) rief bald verhängnisvolle Rufe nach einer „Regierung der harten Hand“ auf die Tagesordnung und bescherte Portugal die längste Phase rechtsautoritärer Herrschaft (1926-1974) im modernen Europa.

Vom konservativen Norden Portugals aus überrollte das Militär unter General Gomes da Costa am 28. Mai 1926 in der „Nationalen Revolution“ innerhalb weniger Tage den letzten Widerstand der Ersten Republik. Der erste Versuch einer Demokratisierung Portugals stand unter keinem guten Stern: Insgesamt verschliss die Republik über 40 Regierungen, erlitt Schiffbruch im Ersten Weltkrieg, wurde von zahlreichen Putschversuchen erschüttert und konnte auch sonst die widerstreitenden Parteien nicht in das republikanische System integrieren. Ideologisch verbunden waren die Generale der daraufhin installierten Militärdiktatur - die auch ganz offiziell so hieß - nur durch ihre antirepublikanische Haltung. Infolgedessen entbrannte zwischen den Militärs ein Machtkampf um die Zukunft Portugals, in welchem sich schließlich António Óscar de Fragoso Carmona 1928 als Präsident durchsetzen konnte.

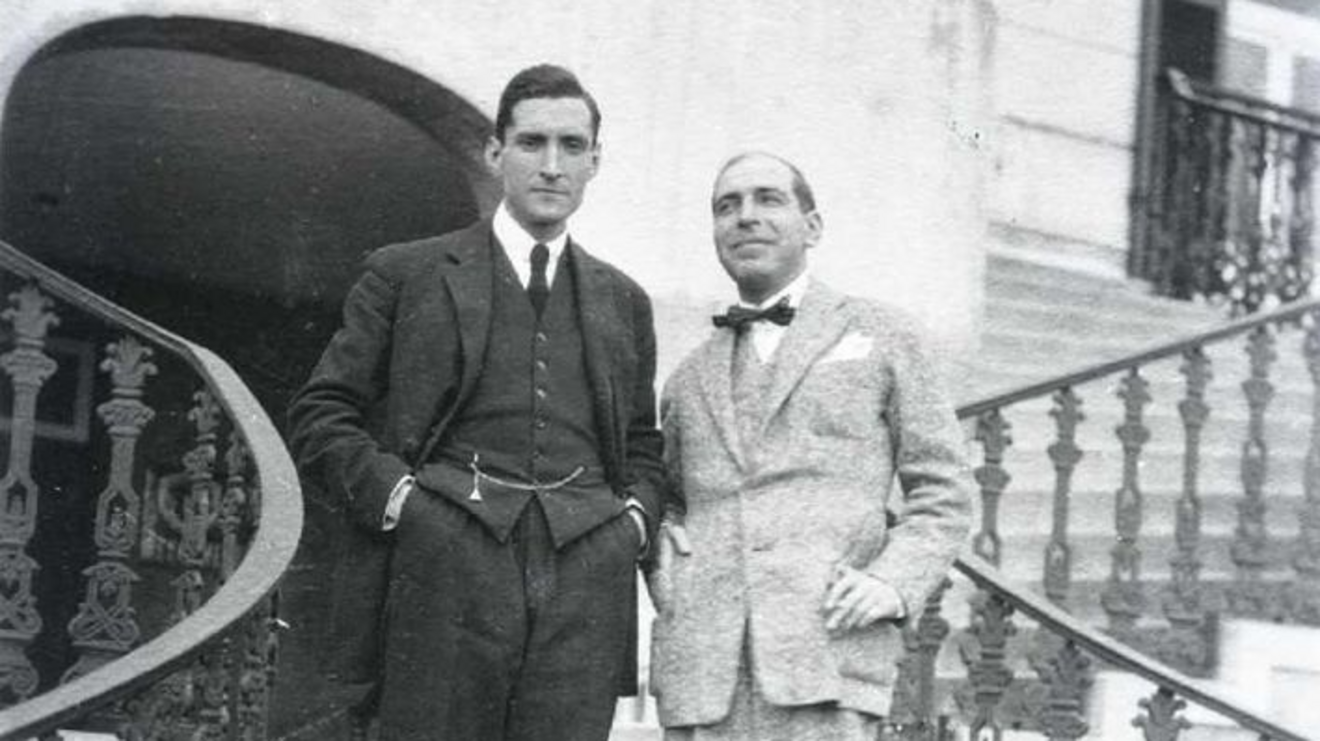

Ein tiefgreifendes Problem des neuen Regimes waren die zerrütteten Staatsfinanzen. Diesem konnten die Militärs aufgrund ihrer mangelnden Wirtschaftsexpertise nicht Herr werden. Abhilfe schaffte ein bis dahin unbekannter Ökonomieprofessor, der 1928 zum Chef des Finanzministeriums bestellt wurde. António de Oliveira Salazar gelang die Sanierung des Staatshaushaltes bereits im ersten Amtsjahr. Mit diesem Erfolg öffnete sich dem Aufsteiger aus der portugiesischen Provinz der Weg zur Macht. Als Protegé des Präsidenten Óscar Carmona überstand Salazar seine mit Kalkül gewählten ersten Machtkämpfe. Die Ernennung Salazars zum Premierminister am 5. Juli 1932 markierte sodann den entscheidenden Schritt zum Estado Novo, zum „Neuen Staat“, der durch die im Folgejahr verabschiedete Verfassung konsolidiert wurde. Die ideologische Ausrichtung des neugeschaffenen katholisch geprägten Ständestaates richtete sich vornehmlich an den Überzeugungen des allmächtigen Premierministers der de facto über den Präsidenten, und die Legislative hinwegregieren konnte.

Eine erste Bewährungsprobe des jungen Regimes stellte der Bürgerkrieg (1936-1939) im benachbarten Spanien dar, da die Durchsetzung der nationalistischen Truppen unter Francisco Franco auch für den Estado Novo überlebenswichtig war. Der in seinen außenpolitischen Ambitionen eher zurückhaltende Salazar kam also nicht umhin, die franquistische Seite mit der Entsendung eines Freiwilligenkorps – der Legion Viriato – zu unterstützen. Ebenso ließ Salazar eine zeitlich beschränkte Massenmobilisierung durch die Schaffung von paramilitärischen Verbänden wie der Portugiesischen Legion und der Portugiesischen Jugend zu. Durch die Übernahme des Saluto romano wiesen die Massenorganisationen augenfällige Annäherungen zu den faschistischen Regimen der Zwischenkriegszeit auf. Deshalb spricht man in diesem Zeitraum auch von einer zeitweisen „Faschisierung“ des Estado Novo.