Museus e instituições em Espanha

O panorama museológico espanhol sobre o tema da guerra civil e da ditadura de Franco é limitado. É sobretudo no País Basco que o passado problemático é exposto. As instituições do Estado e da sociedade civil estão a trabalhar em conjunto para esclarecer a dimensão da repressão.

Numa sala escura do Museu da Paz de Guernica, o passado volta a ganhar vida. Um calendário mostra o dia 26 de abril de 1937. É segunda-feira, dia de mercado, às 16h30m. Um relógio de parede marca a hora. Começam os bombardeamentos, soam as sirenes. O ataque aéreo da Legion Condor alemã, que destruiu quase completamente a pequena cidade basca durante a guerra civil, é recriado de forma impressionante. O museu, fundado em 1998, foi o primeiro em Espanha a abordar o tema da guerra civil. O mais recente museu a abordar o passado turbulento de Espanha, o Centro de Memória das Vítimas do Terrorismo, inaugurado em 2021, situa-se também no País Basco. Localizado na capital regional, Vitoria-Gasteiz, centra-se no terror da ETA que assolou a Espanha desde o final da era franquista até à primeira década do século XXI.

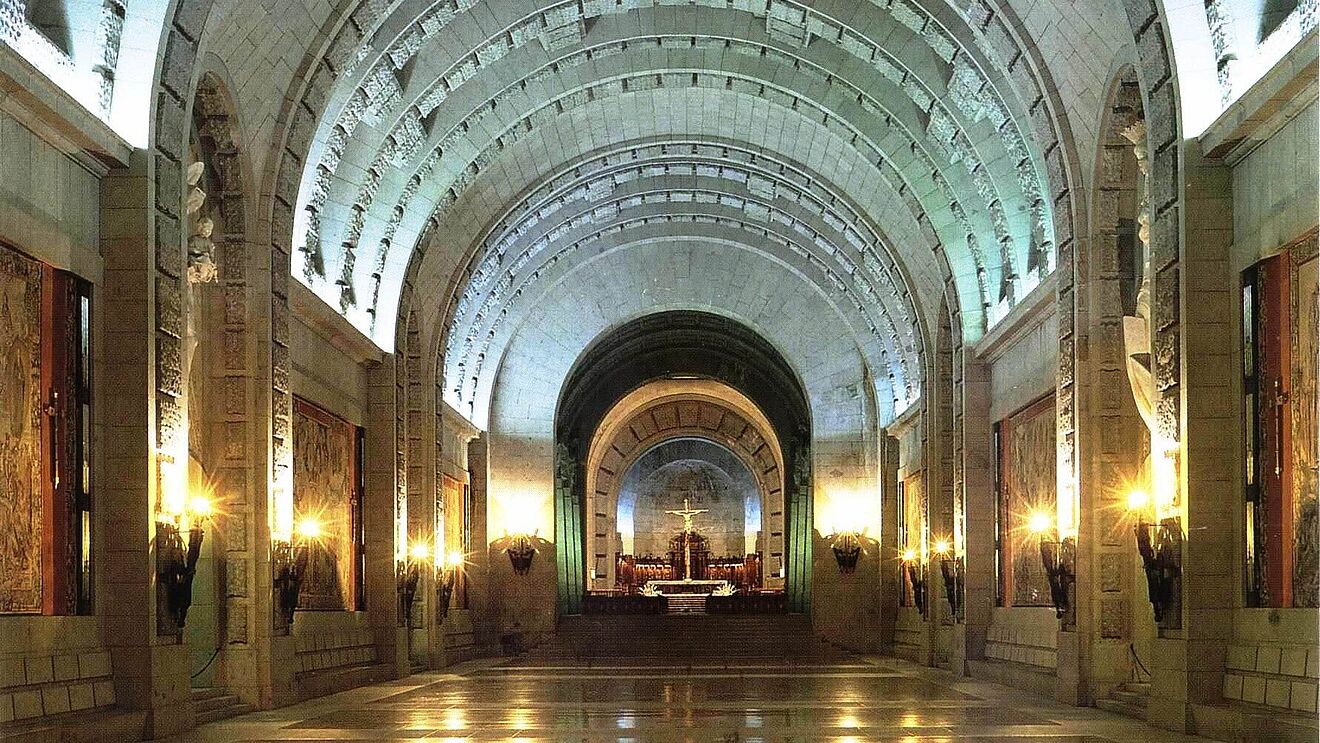

Em nítido contraste com estes museus estão os locais de peregrinação dos nostálgicos da ditadura e os santuários da guerra civil do regime de Franco, sobretudo o "Vale dos Caídos," na Serra de Guadarrama, perto de Madrid. Aqui, 150 metros acima do nível do mar, uma cruz de pedra estende-se sobre uma abóbada de berço escavada na rocha – a basílica onde o ditador foi enterrado, a seu pedido, após a sua morte. Em 2019, por ordem do governo do PSOE do primeiro-ministro Pedro Sánchez, foi exumado e enterrado num panteão familiar. O Alcázar de Toledo recebeu uma remodelação igualmente cautelosa. Neste complexo fortificado, a guarnição nacionalista resistiu a dois meses de ataques e bombardeamentos por parte dos militares republicanos até ser libertada por um exército de socorro sob o comando do general Franco. Enquanto a Biblioteca de Castilla-La Mancha foi transferida para o piso superior em 1998, a exposição nostálgica da ditadura no piso térreo foi integrada no Museu do Exército, inaugurado em 2010, após uma cuidadosa reinterpretação.

Um terceiro pilar da cultura institucional da memória em Espanha é formado por instituições que promovam uma cultura da memória, como o Centro Documental da Memória Histórica (CDMH), em Salamanca, e a Associação para a Recuperação da Memória Histórica (ARMH), em Ponferrada. O CDMH foi criado a partir do antigo centro de recolha de dados do regime franquista, que já durante a guerra civil recolhia informações sobre os republicanos e outros inimigos do futuro regime, a fim de os julgar em tribunais militares após o fim da guerra. Em 1979, a agência, agora desactivada, passou a fazer parte do Ministério da Cultura espanhol, que iniciou uma transformação a longo prazo numa instituição de investigação e revalorização. A ARMH foi fundada em 2000 por iniciativa de Emilio Silva e trabalha para exumar e identificar as vítimas anónimas da guerra civil nas inúmeras valas comuns do país.

Ligações

Sítio web do Museu da Paz de Gernika (espanhol)

Visita virtual ao Centro de Memória das Vítimas do Terrorismo em Vitoria-Gasteiz (espanhol)

O historiador Tyler J. Goldberger sobre a rededicação do "Vale dos Caídos" (inglês, acesso restrito)

Sítio web do Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica (CDMH) de Salamanca (espanhol)

Sítio web da Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (ARMH) (espanhol)

Museen und Institutionen in Portugal

Die Museumslandschaft in Portugal ist noch immer stark von den historischen Anfängen und Sternstunden der eigenen Geschichte geprägt. Erst jüngst ist durch das Engagement der Zivilgesellschaft auch die problematische Zeitgeschichte in das Zentrum der Aufmerksamkeit gerückt worden.

Große krakeelende Menschenmengen, die noch immer ostentativ die Hände zum „römischen Gruß“ erheben – wie dies zuweilen in Spanien und Italien zu beobachten ist –, ist in Portugal die Ausnahme. Dennoch können derartige Entgleisungen in kleinerem Rahmen im Provinzstädtchen Vimieiro nahe Coimbra, der Geburts- und Begräbnisort des ehemaligen Diktators António de Oliveira Salazar, beobachtet werden. Sowohl am Geburtstag als auch am Todestag des Diktators pilgern vereinzelte Saudosistas (Nostalgiker) zum Friedhof des Diktators und verwandeln das beschauliche Dorf in ein kleines Predappio. In dieses Bild passt auch das an Salazars Grab angebrachte Epitaph, das vielmehr eine hagiographische Darstellung als eine kritische Reflexion der historischen Person darstellt. Zu einem Zankapfel wurde das ebenso in Vimieiro befindliche Geburtshaus Salazars. Es sollte in ein Museum umgebaut werden. Das Vorhaben rief jedoch schon seit den ersten Planungen im Jahre 1989 massive Proteste vor allem der linken politischen Kräfte in Portugal hervor. Auch Konzessionen wie die Umwandlung des Geburtshauses in ein „Dokumentationszentrum des Neuen Staats“, in welchem vor allem auch die diktatorische Natur des Regimes betont werden sollte, erzielten bis dato keinen Konsens.

Im diametralen Gegensatz zur inoffiziellen und in ihrem Personenkreis eher begrenzten Salazar-Verehrung steht die offiziell eingetragene zivile Bewegung „Löscht die Erinnerung nicht!“ (NAM). Die NAM formierte sich am 5. Oktober 2005 als Reaktion auf den Verkauf des ehemaligen Hauptquartiers der politischen Polizei der Salazar-Diktatur in Lissabon. Das Versäumnis des portugiesischen Staates, den Ort der diktatorischen Verbrechen als Mahnmal zu nutzen, mobilisierte insbesondere den politischen Willen der ehemaligen Opfer und Oppositionelle der Diktatur. Aus dem zunächst spontanen Zusammenschluss erwuchs eine Organisation mit festen Strukturen, die zu einer wichtigen Konstante der institutionellen Erinnerungsarbeit in Portugal geworden ist. Seit ihrer Gründung hat die NAM zahlreiche Projekte zur Aufarbeitung der Diktatur und zur Würdigung des 25. Aprils angestoßen: Hierzu zählen Museumsprojekte, Monumente und Plaketten zur historischen Kontextualisierung wichtiger Erinnerungsorte im Kontext der Diktaturaufarbeitung.

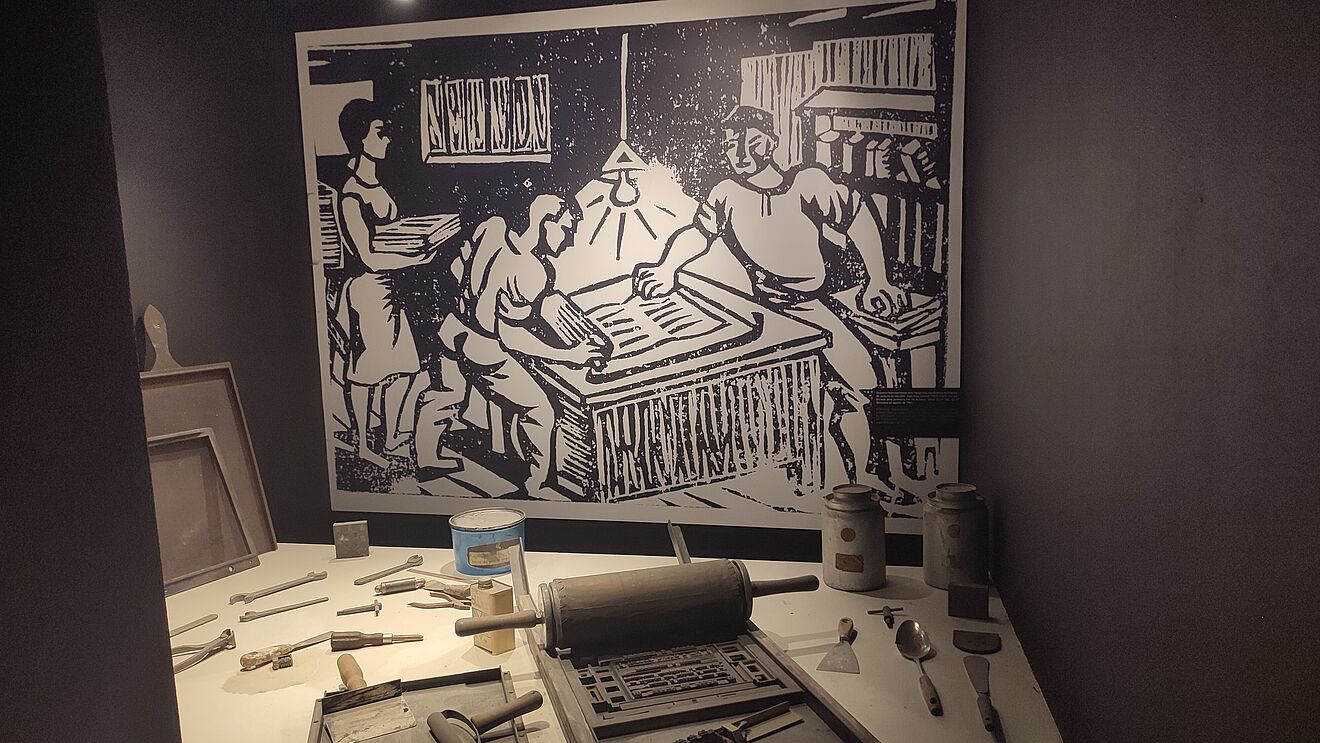

Ganze 50 Jahre sollte es dauern, bis am 25. April 2015 das erste Museum zur Aufarbeitung der Salazar-Diktatur geschaffen wurde. Als bauliche Grundlage diente der Gebäudekomplex des zwischen 1928-1965 betriebenen Gefängnis Aljube für politische Gefangene inmitten Lissabons. Die Umsetzung des Aljube-Museums war nicht von staatlicher Seite initiiert worden, sondern musste vielmehr von zivilgesellschaftlicher Seite hart erkämpft werden. Zu den instrumentellen Akteuren zählten etwa die NAM und der damalige Lissaboner Bürgermeister und gegenwärtige Premierminister Portugals, António Costa. Im Zentrum der Dauerausstellung des Aljube-Museums steht der erbitterte Kampf des Widerstands gegen die Diktatur. Aber auch die Ideologie des Salazarismus, der portugiesische Kolonialkrieg und die demokratiebringende Nelkenrevolution werden im Museum multimedial und ansprechend vermittelt. 2019 folgte die Musealisierung eines weiteren politischen Gefängnisses des „Neuen Staats“ in der Festung Peniche in der gleichnamigen Küstenstadt nördlich von Lissabon. Dass die Macher des neuen Musems in Peniche vom Beispiel Aljube gelernt hatten, ist in der Dauerausstellung von Peniche eindeutig wiederzuerkennen.

Links

Website von „Não apaguem a Memória!“ (NAM) (portugiesisch)

Website des Aljube-Museums (portugiesisch/englisch)

Trailer über das Aljube-Museum (portugiesisch)

YouTube-Kanal des Aljube-Museums mit Zeitzeugeninterviews (portugiesisch)

Website des Museums in Peniche (portugiesisch/englisch/spanisch)

Website des Museums im ehemaligen Konzentrationslager Tarrafal auf Kap Verde (portugiesisch)