Erinnerungsliteratur in Portugal

José Saramago, António Lobo Antunes und Lídia Jorge zählen zu den entscheidenden Gestalten der literarischen Aufarbeitung der problematischen Vergangenheit in Portugal. Noch bevor die Archive der Diktatur und der Kolonialkriege geöffnet werden konnten, riefen sie die vergangenen Gräuel in das Bewusstsein der Bevölkerung.

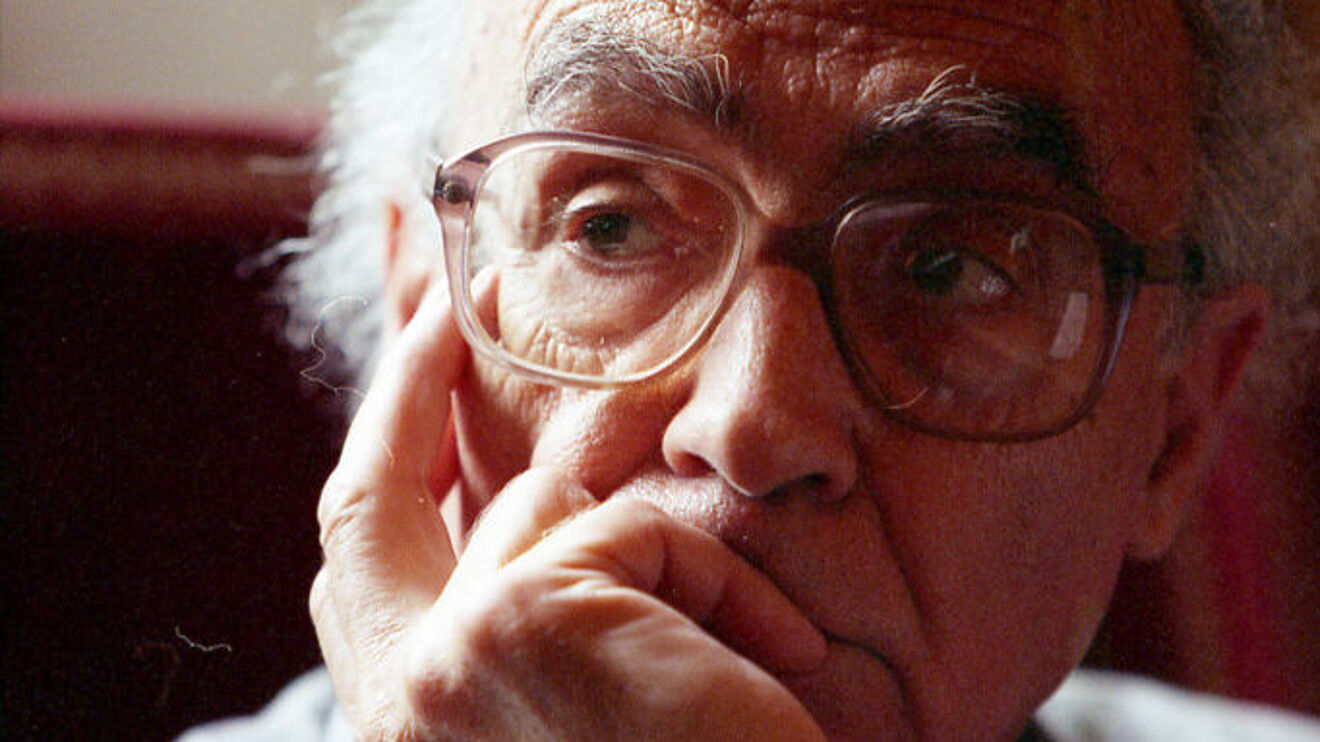

José Saramago, 1922 in armen Verhältnissen im Dorf Azinhaga im Ribatejo geboren, zeitlebens überzeugter Kommunist, sollte bisher als einziger Portugiese 1998 den Nobelpreis für Literatur erhalten. Sein Leben in Opposition zum Estado Novo und der katholischen Kirche bestimmten sein literarisches Œuvre in besonderem Maße. Als Überzeugungstäter beließ es Saramago in seinen Romanen nicht bei der bloßen Erinnerung an die portugiesische Diktatur, vielmehr wird das Frühwerk vom militanten Aktivismus seines Machers getrieben. In Levantado do Chão (1980) beschreibt er im Modus der „Geschichte von unten“ das generationenüberspannende Elend der alentejanischen Landbevölkerung, die am Ende des Werks in der Nelkenrevolution gegen ihre Herren aufbegehrt. In O Ano da Morte de Ricardo Reis (1984) geißelt Saramago die Passivität des pessoanischen Heteronyms Ricardo Reis während der Faschisierung Europas zur Mitte der 1930er Jahre. Den Höhepunkt erreicht Saramagos historiographische Metafiktion im Roman Memorial do Convento (1982), in welchem der Autor historische Parallelen zwischen der Gründung des Nationalpalasts von Mafra durch João V. und der Inauguration des Estado Novo durch Salazar zieht. Das zweifellose Verdienst dieses streitbaren Intellektuellen war es, die häufig vernachlässigte portugiesische Diktatur in das Bewusstsein einer internationalen Öffentlichkeit lanciert zu haben.

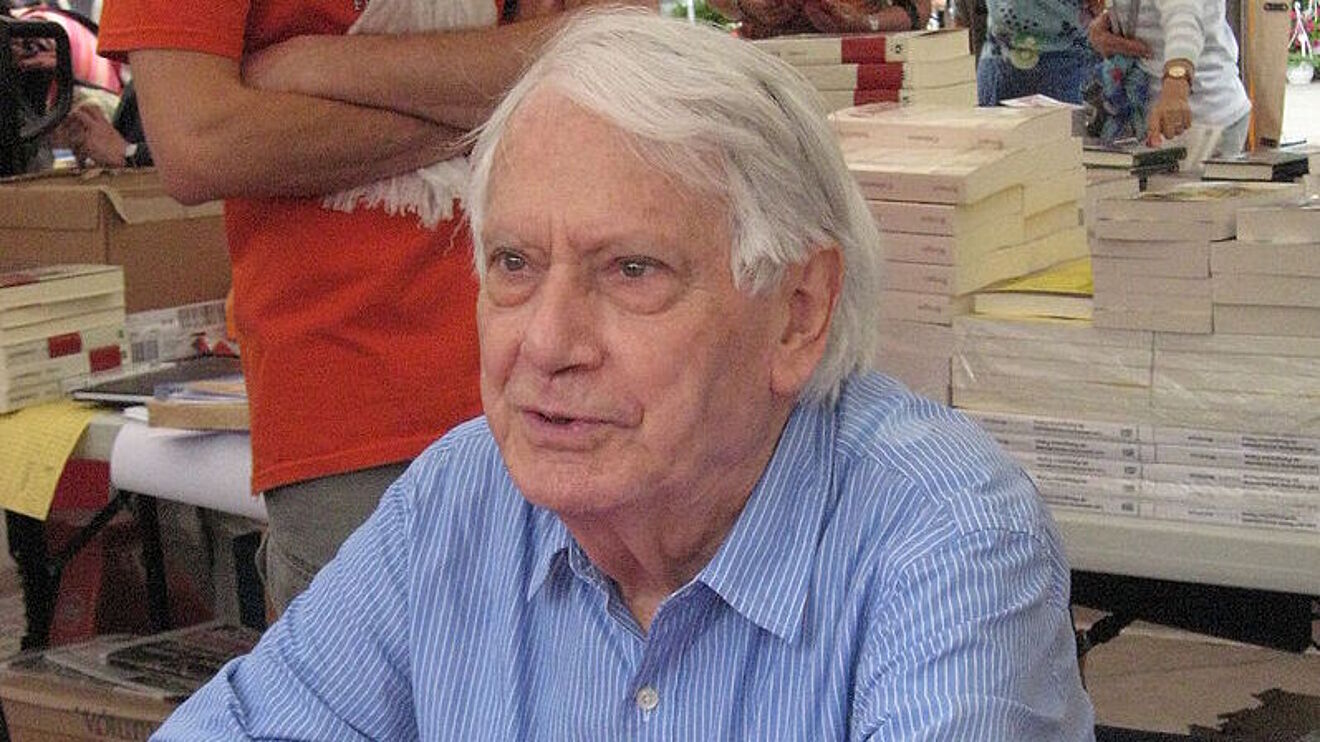

António Lobo Antunes, das „schreibende Gewissen einer gezeichneten Nation“ (Kilanowski), ist mit seinem auf inzwischen über dreißig Romanen angewachsenen Œuvre der Schriftsteller, der die Aufarbeitung problematischer Aspekte der portugiesischen Vergangenheit am intensivsten betrieben hat. Obwohl er 1942 in eine aristokratische und somit im Estado Novo privilegierte Familie in Lissabon hineingeboren wurde, musste Lobo Antunes ab 1971 als Sanitätsoffizier im Kolonialkrieg in Angola dienen. In seiner autobiographischen Debüttrilogie – Mémoria de Elefante (1979), Os Cus de Judas (1979), Conhecimento do Inferno (1980) – arbeitet Lobo Antunes die Traumata des Kolonialkriegs in abschreckenden Details auf. Es folgten zahlreiche Romane über die Pathologien der Salazar-Diktatur wie bspw. im Manual dos Inquisidores (1996). Als postmoderner Dekonstruktivist legte er in As Naus (1988) die Axt an das große Narrativ der portugiesischen Entdeckernation und konterkarierte im Roman Fado Alexandrino (1983) das Erfolgsnarrativ der Nelkenrevolution.

Lídia Jorge zählt zu den wichtigsten Autorinnen der literarischen Aufarbeitung der kolonialen Vergangenheit sowie der Nelkenrevolution im zeitgenössischen Portugal. 1946 in Boliqueime, Algarve, geboren, gehört sie wie António Lobo Antunes zur 1940er Generation. Beide haben sowohl die Kolonialkriege als auch die Nelkenrevolution intensiv miterlebt. Als Offiziersgattin war Lídia Jorge gleich zwei Mal am Kriegsschauplatz: Zunächst in Angola (1968-1970) und später in Mosambik (1972-1974). Die Aufarbeitung der Erfahrungen in Mosambik legte sie beeindruckend im Roman A Costa dos Murmúrios (1988) dar, in welchem sich die Gräuel der portugiesischen Kriegspartei nahezu in ein genozidales Ausmaß steigern. Die Romane O Dia dos Prodígios (1980) und Os Memoráveis (2014) thematisieren beide die Nelkenrevolution, reflektieren sie jedoch auf ganz unterschiedliche Weise. Im ersten Roman wird die Nelkenrevolution aus der Perspektive eines kleinen Dorfes in der portugiesischen Peripherie erzählt. Im Letzteren kehrt eine portugiesische Reporterin aus Washington 2004 in ihr Heimatland zurück, um die Nelkenrevolution anhand von Zeitzeugeninterviews retroperspektivisch aufzuarbeiten und zu würdigen.

Links

BBC-Doku „José Saramago: A Life of Resistance (2002)“ (englisch)

José Saramagos Rede anlässlich der Verleihung des Literaturnobelpreises 1998 (portugiesisch)

Website der José-Saramago-Stiftung (portugiesisch/englisch/spanisch)

Arte-Doku „Das entzauberte Lissabon von António Lobo Antunes (2021)“ (deutsch)

Arte-Doku „Lídia Jorges poetische Algarve (2021)“ (deutsch)

Literatura da memória em Espanha

O tratamento literário do passado recente de Espanha caracteriza-se sobretudo por um fascínio ininterrupto pela guerra civil. Os ideais, os conflitos e as vítimas destes três anos extremos e cheios de perdas estão no centro das reflexões narrativas.

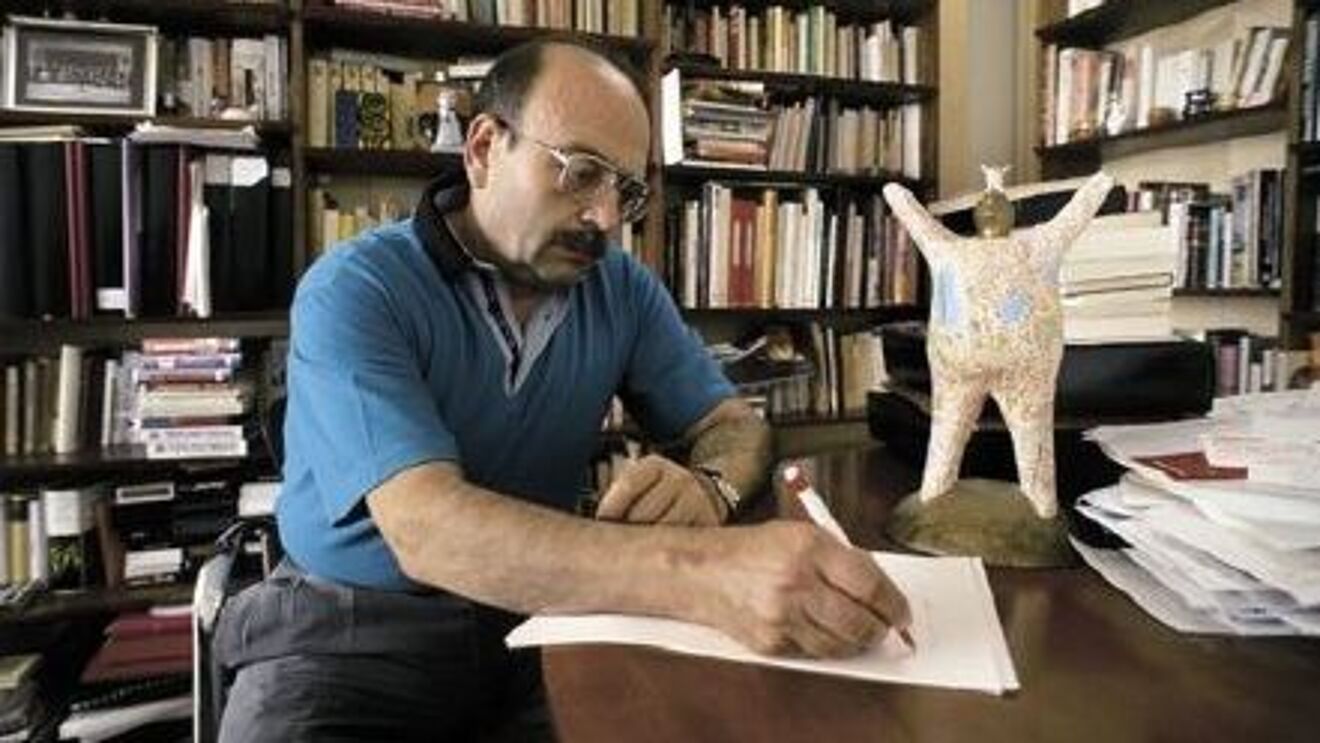

Combatente da Resistência Francesa. Sobrevivente do campo de concentração de Buchenwald. Membro do comité central do Partido Comunista Espanhol. Representante do eurocomunismo moderado, o que levou à sua expulsão do partido em 1964. Ministro da cultura independente no gabinete do PSOE do primeiro-ministro Felipe González. Quase ninguém viveu tão de perto a era dos extremos como Jorge Semprún, nascido em Madrid em 1923. Da sua vida cheia de acontecimentos, o intelectual produziu uma rica obra literária. Os mais conhecidos são os relatos das suas experiências nos campos de concentração, Le grand voyage (1963) e Quel beau dimanche (1980), repletos de uma poética trágica. Com a sua Autobiografía de Federico Sánchez (1977) e as obras posteriores Federico Sánchez vous salue bien (1993), Le mort qu'il faut (2001) e Veinte años y un día (2003), abordou as perdas traumáticas da guerra civil e o preço da transição sob o seu antigo pseudónimo. Em 2003, interveio na comemoração do Dia da Memória das Vítimas do Nacional-Socialismo no Bundestag alemão.

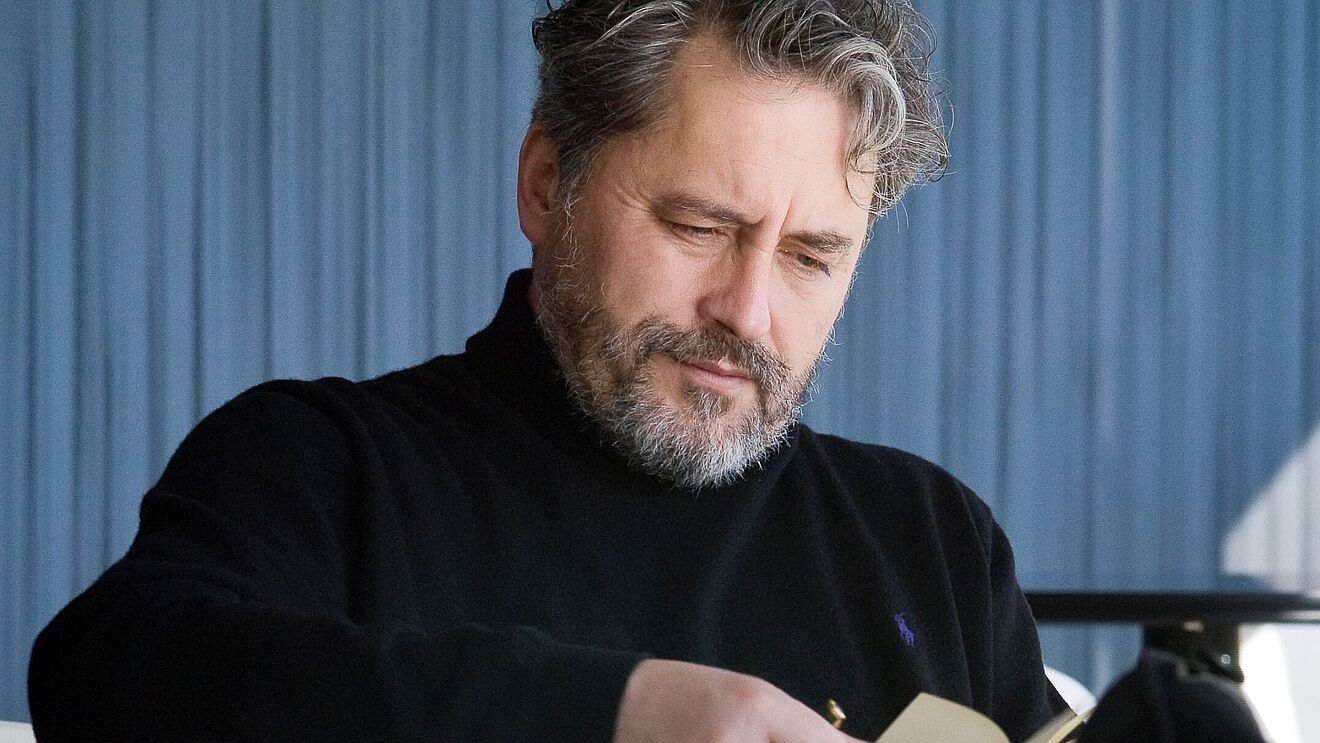

Se Semprún pertenceu à geração dos que viveram em primeira mão a guerra civil e a ditadura de Franco, Javier Cercas (*1962) foi provavelmente um dos expoentes literários mais destacados da geração nascida depois. Ambos os seus pais estiveram do lado dos nacionalistas franquistas na guerra civil: um facto que viria a assombrar Cercas. O doutor em filologia ganhou fama com o romance Soldados de Salamina (2001), no qual o seu protagonista investiga o fundador do partido fascista Falange, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, lançando luz sobre as zonas cinzentas morais da última fase da guerra civil e os ideais dessa geração perdida. Soldados de Salamina, que vendeu um milhão de exemplares, é um romance de não-ficção que mistura entrevistas com registos diários e exegese das fontes com reflexões sobre a fiabilidade das memórias. Cercas manteve-se fiel a este hiper-realismo em Anatomía de un instante (2009) e El monarca de las sombras (2017), em que analisa o golpe de estado de 1981 e a sua própria história familiar, respectivamente.

No entanto, a autora contemporânea mais importante de perspectiva das vítimas é Almudena Grandes (*1960), falecida em 2021, que dedicou o seu ciclo de seis romances, Episodios de una guerra interminable, à resistência antifranquista. Os seus protagonistas, muitas vezes mulheres, dedicam-se a uma luta que dura anos e termina frequentemente em perdas, torturas e morte. A invasão do vale de Aran em 1944 por guerrilheiros exilados em França em Inés y la alegría (2010), a rede espanhola de refugiados nazis alemães na Argentina em Los pacientes del doctor García (2017) e o martírio da feminista Aurora Rodríguez Carballeira na Espanha franquista dos anos 50 em La madre de Frankenstein (2020) são alguns dos acontecimentos reais que servem de base a seu trabalho. Tal como Cercas, Grandes era autor regular de uma coluna no El País. Além disso, o republicano convicto foi durante algum tempo membro da aliança Esquerda Unida. O último romance dos seus Episodios de una guerra interminable, sobre os escondidos na guerra civil (topos), Mariano en el Bidasoa, ficou incompleto.