Cooperation between German Christian Democrats and Spanish Centrists and Conservatives

Distancing themselves as far as possible from the old Francoist elite, the German Christian Democratic Party (CDU) aimed at building up a genuine Spanish Christian democracy during the Transición. In the 1990s, the party moved closer to the right-wing conservatives of the Popular Party (PP).

Little seemed to unite Adolfo Suárez and Helmut Kohl when both received the Prince of Asturias Award in Oviedo on November 8, 1996. While the former Spanish prime minister spoke of the achievements of democratization in his acceptance speech, Kohl's address focused entirely on European integration. Both mentioned each other with only a few words, although they saw themselves as members of the same party family – European Christian Democracy. Unlike the Social Democrats, the German CDU had long been estranged from its Spanish partners. In the 1960s, the Adenauer, Erhard, and Kiesinger governments had pursued a course of normalization toward Franco's Spain and were susceptible to the dictator's request to be admitted to the EEC. In the European Documentation and Information Center (CEDI) coordinated by Otto von Habsburg, the CDU maintained contacts with politicians of the state party. Only their loss of power in 1969 forced the German conservatives to rely on party-political work with opposition Christian Democrats for international networking.

In the period of democratic transition, however, the CDU had experienced a double defeat. First, it had supported the Christian Democratic Team of the Spanish State (EDCEE) – a conglomerate of five Christian Democratic parties who disagreed with each other over their general political direction. Although the anti-Francoism of the central EDCEE figures José María Gil-Robles and Joaquín Ruiz-Giménez was appreciated by the CDU party headquarters in Bonn, the alliance's increasingly left-wing course caused concern. In the spring of 1977, the CDU shifted its support to the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), which was absorbed into the victorious Union of the Democratic Center (UCD) of Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez before the mid-1977 elections. Despite reservations about former Francoists in the ranks of the UCD – including the prime minister himself – the German Christian Democrats now rallied behind the party, which they supported primarily through training at their Humanism and Democracy Foundation (FHD), founded in 1977. After their 1982 electoral defeat, the UCD dissolved due to internal strife. The CDU thus once again found itself without a Spanish partner.

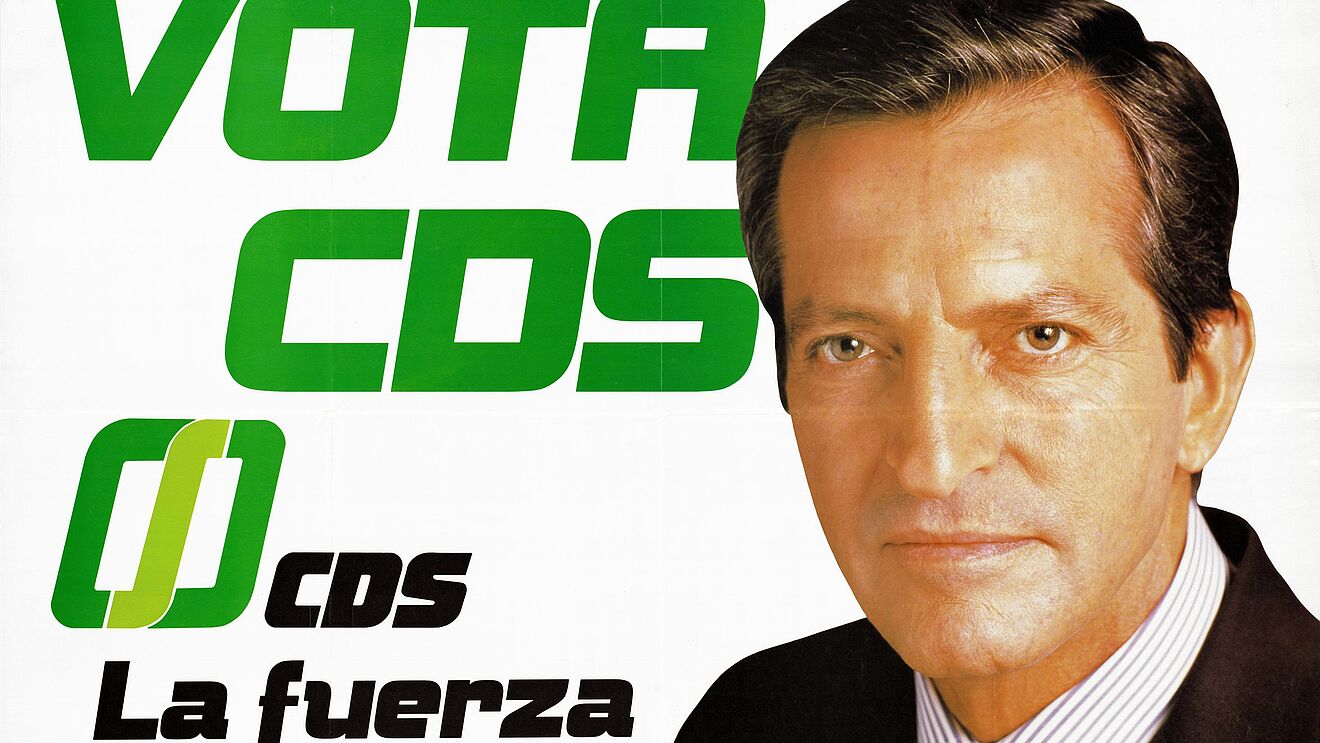

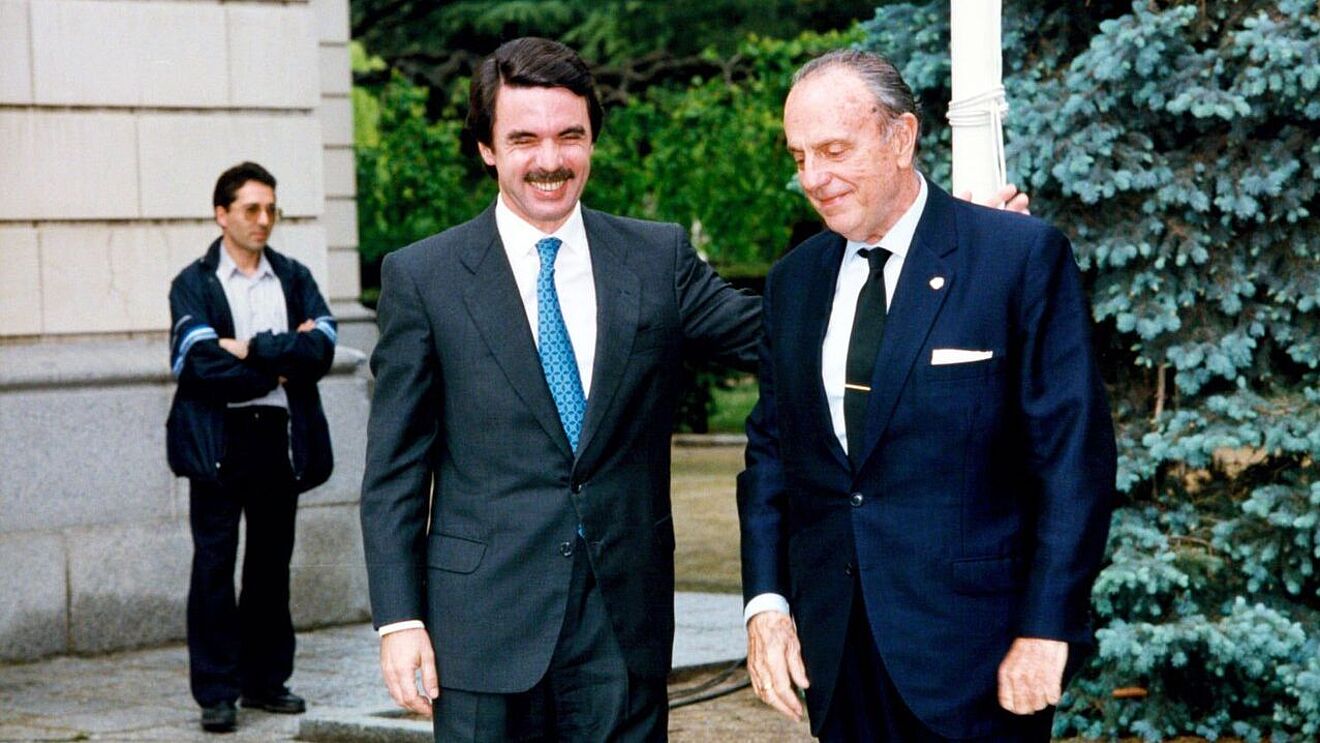

By the 1980s, however, the major problem of the German conservatives had been resolved. After the end of the social-liberal coalition in 1982, the CDU was once again in the government. The good relationship between CDU Chancellor Helmut Kohl and his socialist Spanish counterpart Felipe González gave little reason to invest a great deal of energy in building Christian democracy in Spain. Moreover, the new Democratic and Social Center (CDS) of ex-Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez failed miserably in the 1986 and 1989 parliamentary elections. The party spectrum to the right of the political center now rallied around the conservative Popular Alliance (AP), founded by former Franco minister Manuel Fraga. Through the inclusion of numerous former UCD members, an increasing orientation towards liberal economics, as well as the generational change from Fraga to José María Aznar at the 1989 party congress, the Alliance, now renamed the People's Party (PP), moved closer to the CDU. The final closing of ranks between the CDU and the PP in the 1990s had already been preceded by a long period of cooperation between AP and the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU). CSU Chairman Franz Josef Strauß had seen Fraga as the natural ally of the CDU/CSU as early as 1976.

Cooperation between German Christian Democrats and Portuguese Conservatives

The CDU’s cooperation with Portuguese Christian Democracy had a great impact despite some initial difficulties. The first task was to integrate the Portuguese partner into European Christian Democracy, whereupon numerous projects in Portugal itself were supported.

Unlike the SPD, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its party-affiliated Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) had substantially greater difficulties in finding a suitable cooperation partner in Portugal. After all, conservative circles in revolutionary Portugal were under general suspicion as being the “new generation” of the old regime. After initial exploratory trips at the beginning of May 1974, it seemed that a suitable partner had been found in the People’s Democratic Party (PPD). During the revolution, however, the PPD cultivated the self-image of a social democratic party, before developing into a classic centre-right party in post-revolutionary Portugal. Consequently, it rejected the advances of the CDU. After these initial failures, two newly-founded parties moved into the centre of attention: firstly, the Catholic Conservative Party of Christian Democracy (PDC), founded in May 1974, and secondly, the Democratic and Social Centre (CDS), founded in July 1974. The PDC was not admitted to the elections until 1976 and continued to exist on the fringes of political life, which is why the CDS was finally elected.

“CDS equals fascists, the fascist rabble lives on, open fire on the CDS”. The CDS faced these hostilities from a mob of demonstrators during its first party congress in January 1975. Only the presence of numerous members of the European Union of Christian Democrats (EUCD) – with the president of the EUCD, Kai-Uwe von Hassel, being the most important among them – helped to prevent the situation in front of the Crystal Palace in Porto from escalating further. For the time being, the integration of Portuguese Christian Democracy into European Christian Democracy remained von Hassel’s highest priority in association with the CDU’s Office of Foreign Relations and the KAS. With the admission of the CDS as a full member of the EUCD on 5th May 1975, this immediate objective was achieved. The perseverance of the CDS and its German supporters had already paid off in the elections of April 1975, when the CDS was able to garner 7.6 per cent of the electoral votes. In the following year, its share of the vote more than doubled (15.9 %), making the CDS the third-strongest party in Portugal, even ahead of the PCP. Numerous CDS politicians involved in the election campaign had participated in KAS seminars in Sankt Augustin beforehand.

“We do more than the SPD!” That had been the claim made by Helmut Kohl in 1979. In fact, from 1975 onwards, the CDU’s initial moral support for the CDS was augmented by significant financial and political support. The cornerstone for the most financially extensive project of the KAS in Portugal, the Institute for Democracy and Freedom (IDL), was laid on 6th October 1975. The Institute became a gathering point for the party’s prominent figures and provided a training ground for the next generation of CDS politicians. In 1979, for instance, the IDL also met the demand of setting up the Federation of Christian Democratic Workers (FTDC), in order to make a Christian Democratic contribution to the trade union movement. In the same year, another local political institute, the Fontes Pereira de Melo Institute (IFPM), was founded for educational purposes. In total, the cooperation of the KAS with the IDL and the IPFM was to last for more than eighteen years.