The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Hardly any event shaped Spanish history as much as the three-year civil war. Even today, the after-effects of the conflict, which separated society into two camps – nationalists and republicans and, later, victors and vanquished – remain perceptible.

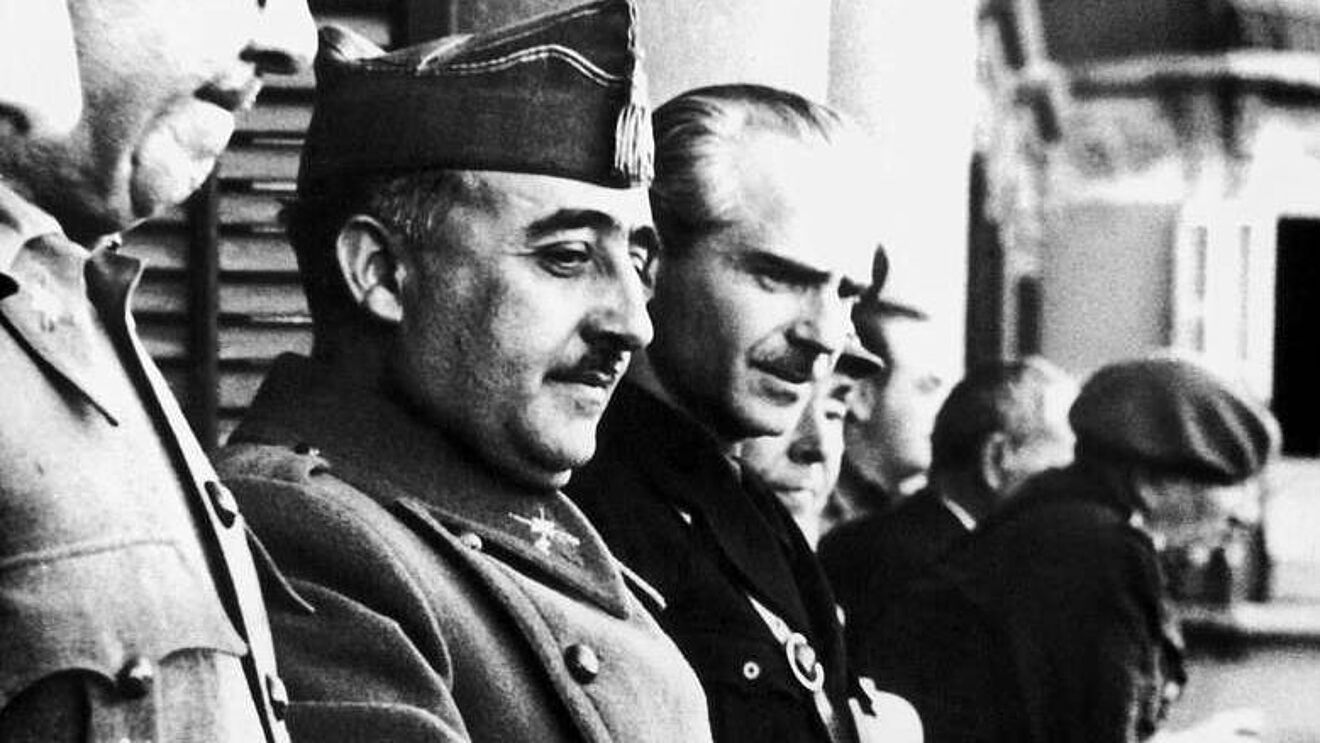

“Spaniards! […] The nation calls upon you for its defense!” With these words General Francisco Franco Bahamonde called for a coup against the Spanish Republic on July 18, 1936. The highly decorated and influential military officer, who had earned a reputation in the Spanish-Moroccan War (1921–1926), was a latecomer to the coup d’état. Ten years earlier, Spain had already been under the rule of a military dictator, General Primo de Rivera. After the fall of Primo in 1931, the Spanish King Alfonso XIII. fled the country, as he had politically supported the dictator. The Second Republic, declared on April 14, 1931, was soon dominated by socialist and reformist forces, who aimed at overcoming Spain’s backwardness as regards central European modernity. The four central reform projects of the Republican governments – land reform, separation of church and state, reduction of the officer corps, autonomy for Catalonia and the Basque Country – met with the disdain of the traditional elites.

In this climate of societal polarization, the army once again reached for power. Planned as quick coup de grâce, the military takeover turned into a long and strenuous civil war, in which Spain slowly bled to death. While the central cities and industrial centers like Madrid, Barcelona and Bilbao, in addition to major parts of the south and the east, initially remained under the control of the Republic, the putschists won in Galicia and North Castille, as well as on the Balearic and Canary Islands. While the frequently irregular combat units of socialists, communists, anarchists, and progressive moderates fought for the Republic, conservatives, nationalists, devout Catholics, monarchists, and the fascist Falange Party supported the military coup. In this sense, the conflict between civil and military leadership developed into a “fratricidal war,” in which the ideal of a progressive, egalitarian, secular and autonomist Spain collided with the conception of the “eternal Spain” of Catholic faith, territorial unity, and the hegemony of monarchy, church, and the military.

The Spanish Civil War became the battlefield of European ideologies in an age of extremes. From early on, the putschists enjoyed the support of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. German JU 52 planes thus carried the putschist Army of Africa from Morocco across the Strait of Gibraltar. The flying squadron of the German Legion Condor and the Italian Aviazione Legionaria bombarded Guernica, the holy city of the Basque Country, destroying it almost completely. In the meantime, the Spanish Republic received arms shipments, ammunition, and T-26 tanks from the Soviet Union, paid for by the Banco de España. The Communist International mobilized approximately 50,000 combatants from all across Europe for the International Brigades. The liberal democracies of the West (France, Great Britain, and the United States) opted for a policy of nonintervention and thereby indirectly contributed to the victory of the nationalist military under General Franco. After three years, approximately 300,000 casualties, and 500,000 refugees, the war ended on April 1, 1939.

Links

Catalogue of Civil War Posters with Explanations (English)

The Truth about Franco: Rise to Power - First Part of a Four-Part ZDF Documentary (German)

Classic Work on the German Left during the Spanish Civil War by Patrik von zur Mühlen (German)

Historian Ali Al Tuma on Franco's Moroccan auxiliary troops during the Civil War (English)

Military Coup and the Emergence of the Estado Novo (1926-1933)

After sixteen years, the first attempt in Portugal to lead the country along a democratic path failed. The instability of the First Republic (1910-1926) soon led to disastrous cries for a "hard-line government" and gave Portugal the longest period of right-wing authoritarian rule (1926-1974) in modern Europe.

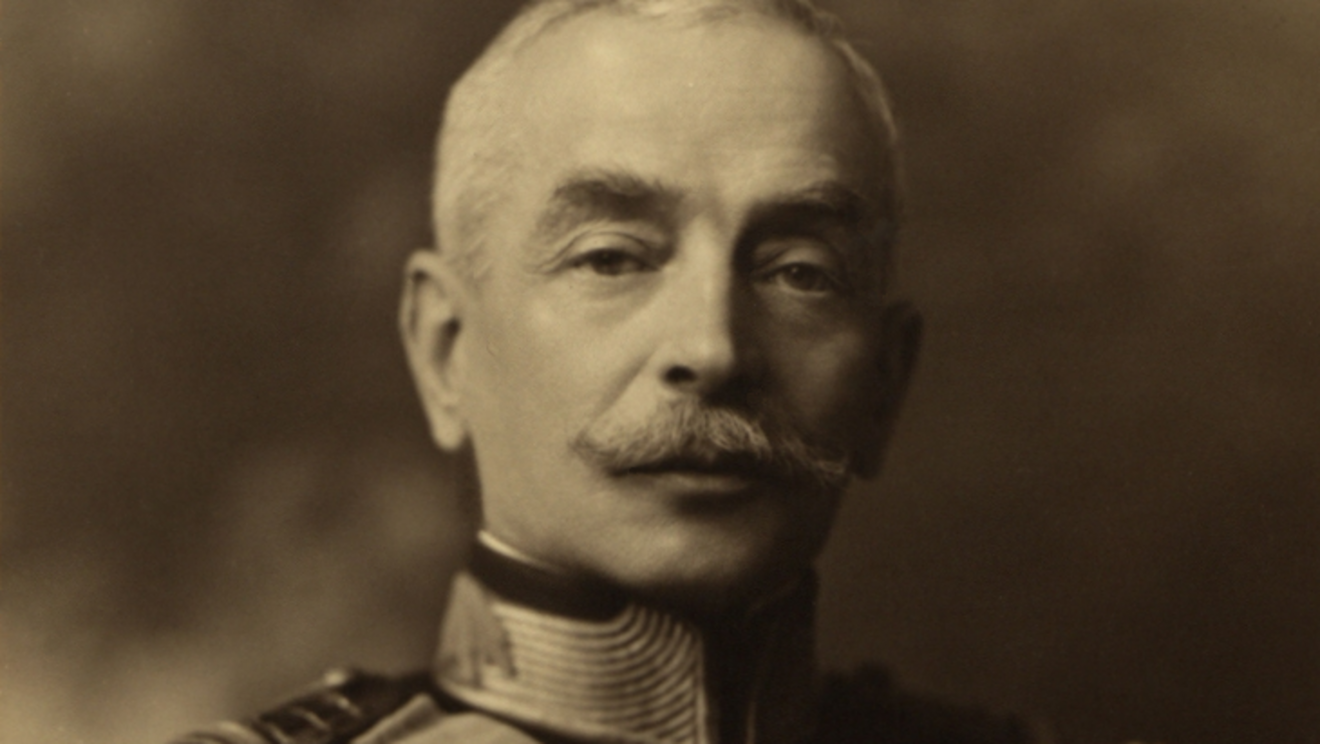

From the conservative north of Portugal, the military under General Gomes da Costa overwhelmed the last resistance of the First Republic within a few days on 28 May 1926 in the "National Revolution". The first attempt at democratisation in Portugal had been ill-fated: In total, the Republic wore out more than 40 governments, suffered shipwreck in the First World War, was shaken by numerous coup attempts and was also otherwise unable to integrate the conflicting parties into the Republican system. Ideologically, the generals were only connected to the military dictatorship – that was installed in the aftermath of the coup - through their anti-republican stance. As a result, a power struggle broke out between the military over the future of Portugal, in which António Óscar de Fragoso Carmona was finally able to assert himself as president in 1928.

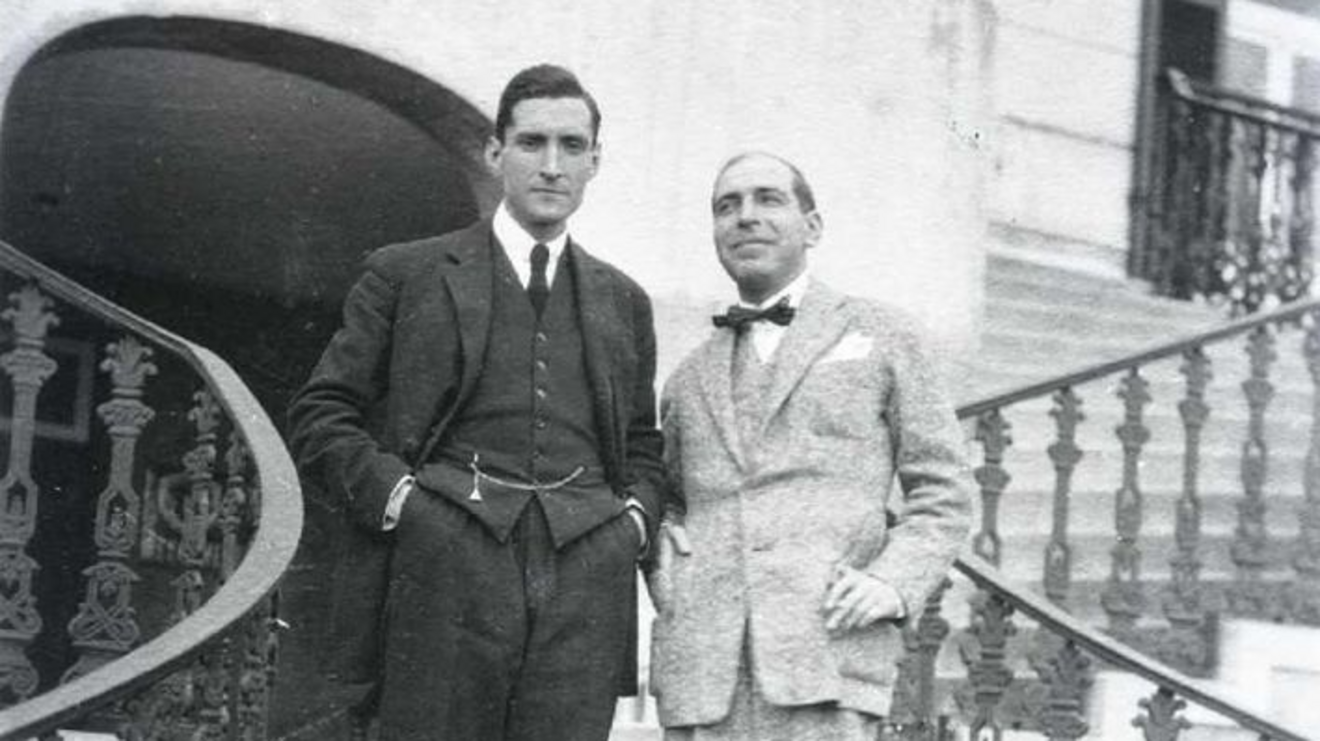

A profound problem of the new regime had been the chaotic state finances. The militaries were not able to cope with the issue at hand because of their lack of economic expertise. A hitherto unknown economics professor, who was appointed head of the finance ministry in 1928, provided a remedy. António de Oliveira Salazar succeeded in reorganising the state budget in his first year in office. This success opened the way to power for the up-and-comer from the Portuguese province. As a protégé of President Óscar Carmona, Salazar survived his first power struggles, which were chosen with caution. Salazar's appointment as prime minister on 5 July 1932 marked the decisive step towards the Estado Novo, the "New State", which was consolidated by the constitution adopted the following year. The ideological orientation of the newly created Catholic-influenced corporative state was primarily based on the convictions of the all-powerful prime minister, who could de facto overrule the president and the legislature.

The first test of the young dictatorship was the Civil War (1936–1939) in neighbouring Spain, since the reinforcement of the nationalist troops under Francisco Franco had also been vital for the survival of the Estado Novo. Salazar, who was rather reserved in his foreign policy ambitions, therefore had no choice but to support the Francoist side by sending a volunteer corps to Spain – the Legion Viriato. Similarly, Salazar allowed for temporary mass mobilisation through the creation of paramilitary units such as the Portuguese Legion and the Portuguese Youth. By adopting the Saluto romano, these mass organisations showed striking similarities to the fascist regimes of the interwar period. This is why it is possible to speak of a “fascisation” of the Estado Novo during this period.