Museos e instituciones en España

El panorama museístico español sobre el tema de la guerra civil y la dictadura franquista es limitado. Es especialmente en el País Vasco, donde se expone el pasado problemático. Instituciones estatales y de la sociedad civil trabajan en conjunto para esclarecer el tamaño de la represión.

En un salón a oscuras del Museo de la Paz de Gernika, el pasado vuelve a cobrar vida. Un calendario muestra el 26 de abril de 1937. Es lunes, día de mercado, 16.30 horas. Un reloj de pared marca la hora. Comienzan los bombardeos, suenan las sirenas. El ataque aéreo de la Legion Condor alemana, que destruyó casi por completo la pequeña ciudad vasca durante la guerra civil, se recrea de forma impresionante. El museo, fundado en 1998, fue el primero de España en abordar el tema de la guerra civil. El último museo en abordar el turbulento pasado de España, el Centro Memorial de las Víctimas del Terrorismo, inaugurado en 2021, también se encuentra en el País Vasco. Situado en la capital regional Vitoria-Gasteiz, se centra en el terror de ETA que asoló España desde el tardofranquismo hasta la primera década del siglo XXI.

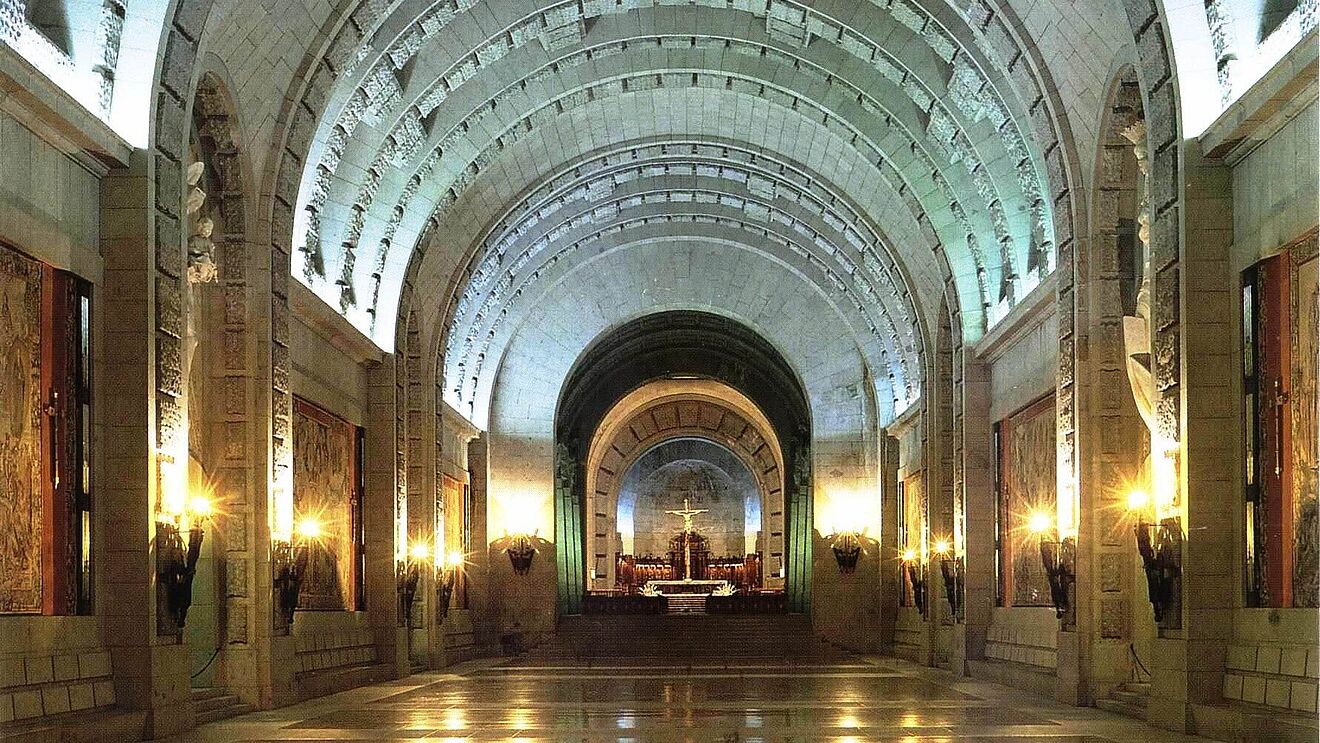

En agudo contraste con estos museos parecen los lugares de peregrinación de los nostálgicos de la dictadura y los santuarios de la guerra civil del régimen de Franco, sobre todo el "Valle de los Caídos" en la Sierra de Guadarrama, cerca de Madrid. Aquí, a 150 metros de altura, una cruz de piedra se extiende sobre una bóveda de cañón tallada en la roca – la basílica donde el dictador fue enterrado a petición propia tras su muerte. En 2019, a instancias del gobierno del PSOE del presidente del gobierno Pedro Sánchez, fue exhumado y enterrado en un panteón familiar. El Alcázar de Toledo recibió una remodelación igualmente cautelosa. En este complejo fortificado, la guarnición nacionalista resistió dos meses de ataques y bombardeos de los militares republicanos hasta que fue liberada por un ejército de socorro al mando del general Franco. Mientras que la Biblioteca de Castilla-La Mancha se trasladó a la planta superior en 1998, la exposición nostálgica de la dictadura de la planta baja se integró en el Museo del Ejército, inaugurado en 2010, tras una cuidadosa reinterpretación.

Un tercer pilar de la cultura institucional del recuerdo en España lo forman instituciones que promueven una cultura de memoria como el Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica (CDMH) de Salamanca y la Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (ARMH) de Ponferrada. El CDMH surgió del antiguo centro de recogida de datos del régimen franquista, que ya durante la guerra civil recopilaba informaciones sobre republicanos y otros enemigos del futuro régimen para juzgarlos en tribunales militares tras el fin de la contienda. En 1979, la ahora desdentada agencia pasó a depender del Ministerio de Cultura español, que inició una transformación a largo plazo a una institución de investigación y revalorización. La ARMH fue fundada en 2000 por iniciativa de Emilio Silva y trabaja para exhumar e identificar a las víctimas anónimas de la guerra civil en las innumerables fosas comunes del país.

Enlaces

Página web del Museo de la Paz de Gernika (español)

Recorrida virtcual del Centro Memorial de las Víctimas de Terrorismo en Vitoria-Gasteiz (español)

Página web del Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica (CDMH) en Salamanca (español)

Página web de la Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (ARMH, español)

Museen und Institutionen in Portugal

Die Museumslandschaft in Portugal ist noch immer stark von den historischen Anfängen und Sternstunden der eigenen Geschichte geprägt. Erst jüngst ist durch das Engagement der Zivilgesellschaft auch die problematische Zeitgeschichte in das Zentrum der Aufmerksamkeit gerückt worden.

Große krakeelende Menschenmengen, die noch immer ostentativ die Hände zum „römischen Gruß“ erheben – wie dies zuweilen in Spanien und Italien zu beobachten ist –, ist in Portugal die Ausnahme. Dennoch können derartige Entgleisungen in kleinerem Rahmen im Provinzstädtchen Vimieiro nahe Coimbra, der Geburts- und Begräbnisort des ehemaligen Diktators António de Oliveira Salazar, beobachtet werden. Sowohl am Geburtstag als auch am Todestag des Diktators pilgern vereinzelte Saudosistas (Nostalgiker) zum Friedhof des Diktators und verwandeln das beschauliche Dorf in ein kleines Predappio. In dieses Bild passt auch das an Salazars Grab angebrachte Epitaph, das vielmehr eine hagiographische Darstellung als eine kritische Reflexion der historischen Person darstellt. Zu einem Zankapfel wurde das ebenso in Vimieiro befindliche Geburtshaus Salazars. Es sollte in ein Museum umgebaut werden. Das Vorhaben rief jedoch schon seit den ersten Planungen im Jahre 1989 massive Proteste vor allem der linken politischen Kräfte in Portugal hervor. Auch Konzessionen wie die Umwandlung des Geburtshauses in ein „Dokumentationszentrum des Neuen Staats“, in welchem vor allem auch die diktatorische Natur des Regimes betont werden sollte, erzielten bis dato keinen Konsens.

Im diametralen Gegensatz zur inoffiziellen und in ihrem Personenkreis eher begrenzten Salazar-Verehrung steht die offiziell eingetragene zivile Bewegung „Löscht die Erinnerung nicht!“ (NAM). Die NAM formierte sich am 5. Oktober 2005 als Reaktion auf den Verkauf des ehemaligen Hauptquartiers der politischen Polizei der Salazar-Diktatur in Lissabon. Das Versäumnis des portugiesischen Staates, den Ort der diktatorischen Verbrechen als Mahnmal zu nutzen, mobilisierte insbesondere den politischen Willen der ehemaligen Opfer und Oppositionelle der Diktatur. Aus dem zunächst spontanen Zusammenschluss erwuchs eine Organisation mit festen Strukturen, die zu einer wichtigen Konstante der institutionellen Erinnerungsarbeit in Portugal geworden ist. Seit ihrer Gründung hat die NAM zahlreiche Projekte zur Aufarbeitung der Diktatur und zur Würdigung des 25. Aprils angestoßen: Hierzu zählen Museumsprojekte, Monumente und Plaketten zur historischen Kontextualisierung wichtiger Erinnerungsorte im Kontext der Diktaturaufarbeitung.

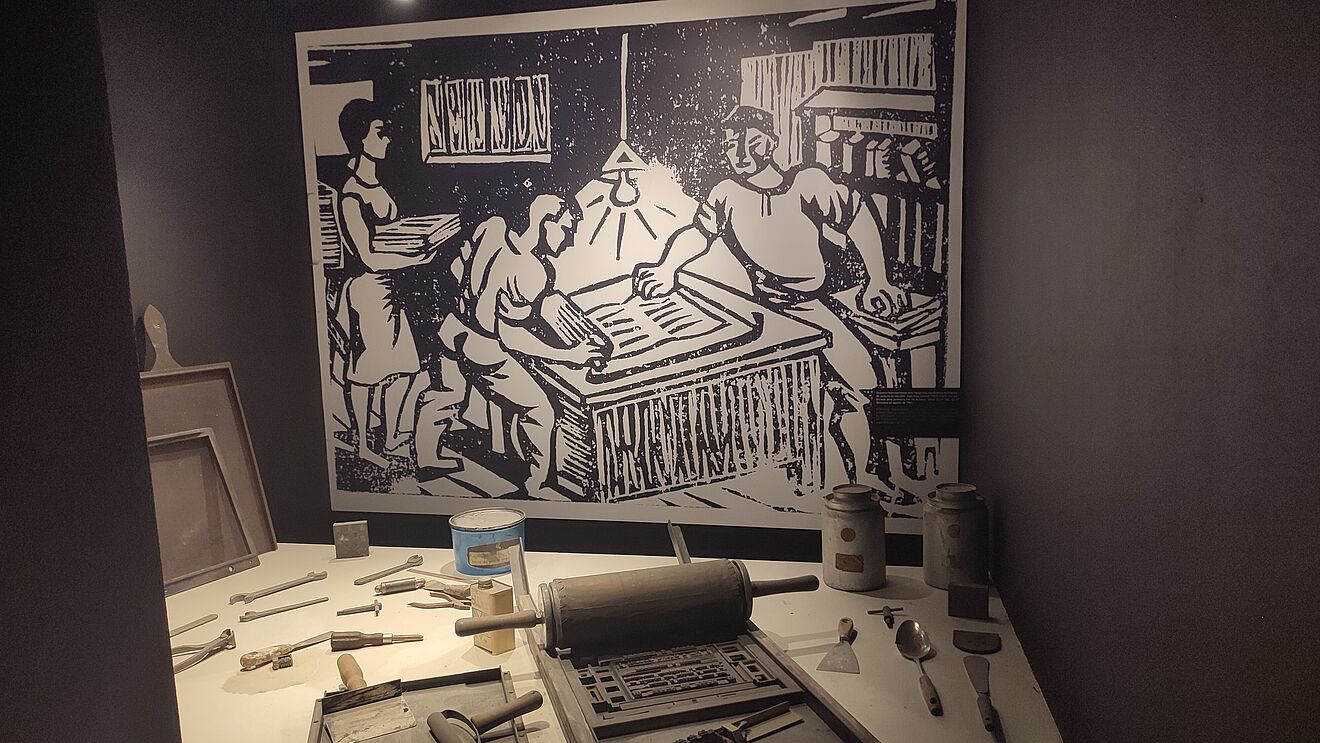

Ganze 50 Jahre sollte es dauern, bis am 25. April 2015 das erste Museum zur Aufarbeitung der Salazar-Diktatur geschaffen wurde. Als bauliche Grundlage diente der Gebäudekomplex des zwischen 1928-1965 betriebenen Gefängnis Aljube für politische Gefangene inmitten Lissabons. Die Umsetzung des Aljube-Museums war nicht von staatlicher Seite initiiert worden, sondern musste vielmehr von zivilgesellschaftlicher Seite hart erkämpft werden. Zu den instrumentellen Akteuren zählten etwa die NAM und der damalige Lissaboner Bürgermeister und gegenwärtige Premierminister Portugals, António Costa. Im Zentrum der Dauerausstellung des Aljube-Museums steht der erbitterte Kampf des Widerstands gegen die Diktatur. Aber auch die Ideologie des Salazarismus, der portugiesische Kolonialkrieg und die demokratiebringende Nelkenrevolution werden im Museum multimedial und ansprechend vermittelt. 2019 folgte die Musealisierung eines weiteren politischen Gefängnisses des „Neuen Staats“ in der Festung Peniche in der gleichnamigen Küstenstadt nördlich von Lissabon. Dass die Macher des neuen Musems in Peniche vom Beispiel Aljube gelernt hatten, ist in der Dauerausstellung von Peniche eindeutig wiederzuerkennen.

Links

Website von „Não apaguem a Memória!“ (NAM) (portugiesisch)

Website des Aljube-Museums (portugiesisch/englisch)

Trailer über das Aljube-Museum (portugiesisch)

YouTube-Kanal des Aljube-Museums mit Zeitzeugeninterviews (portugiesisch)

Website des Museums in Peniche (portugiesisch/englisch/spanisch)

Website des Museums im ehemaligen Konzentrationslager Tarrafal auf Kap Verde (portugiesisch)