Cooperation between German Social Democrats and the Portuguese Socialist Party

From the founding of the party on the premises of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES) to its rise to become the leading party in Portugal, the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS) was actively accompanied its comrades in the SPD. The friendship between Mário Soares and Willy Brandt is emblematic of this cooperation.

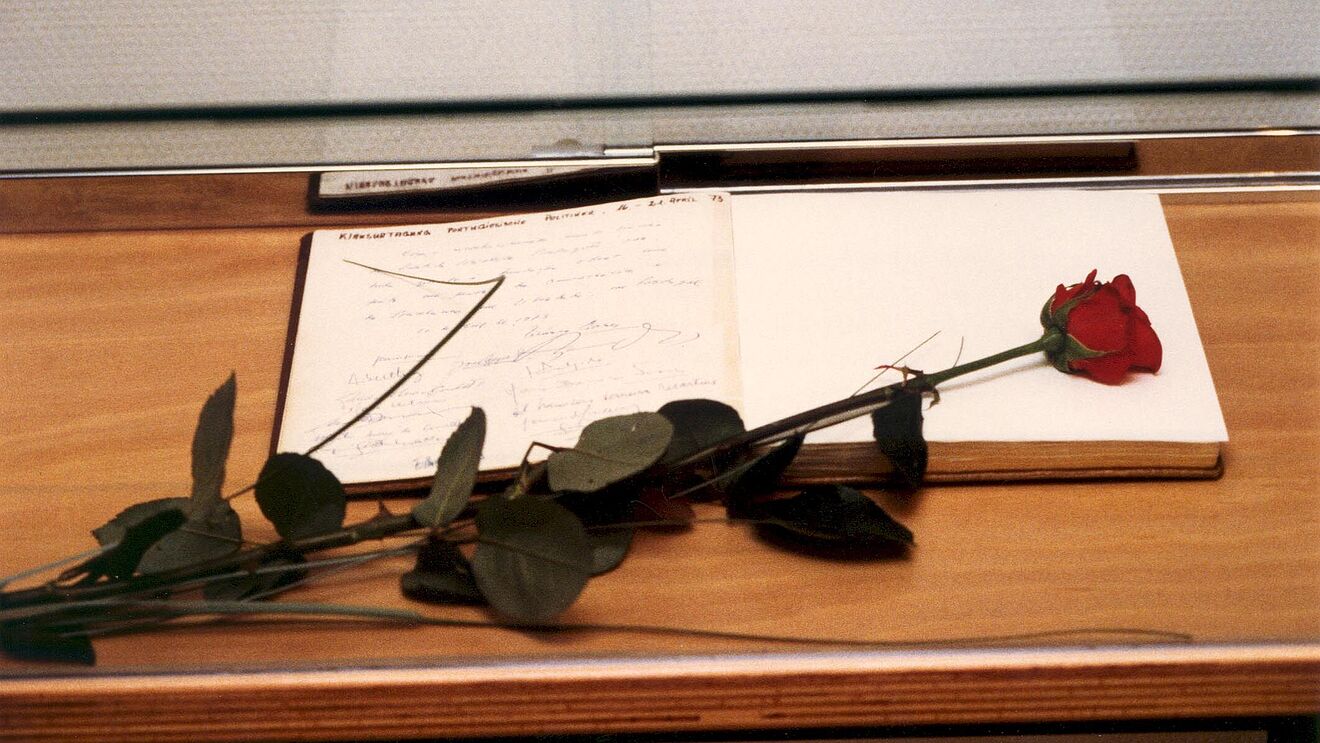

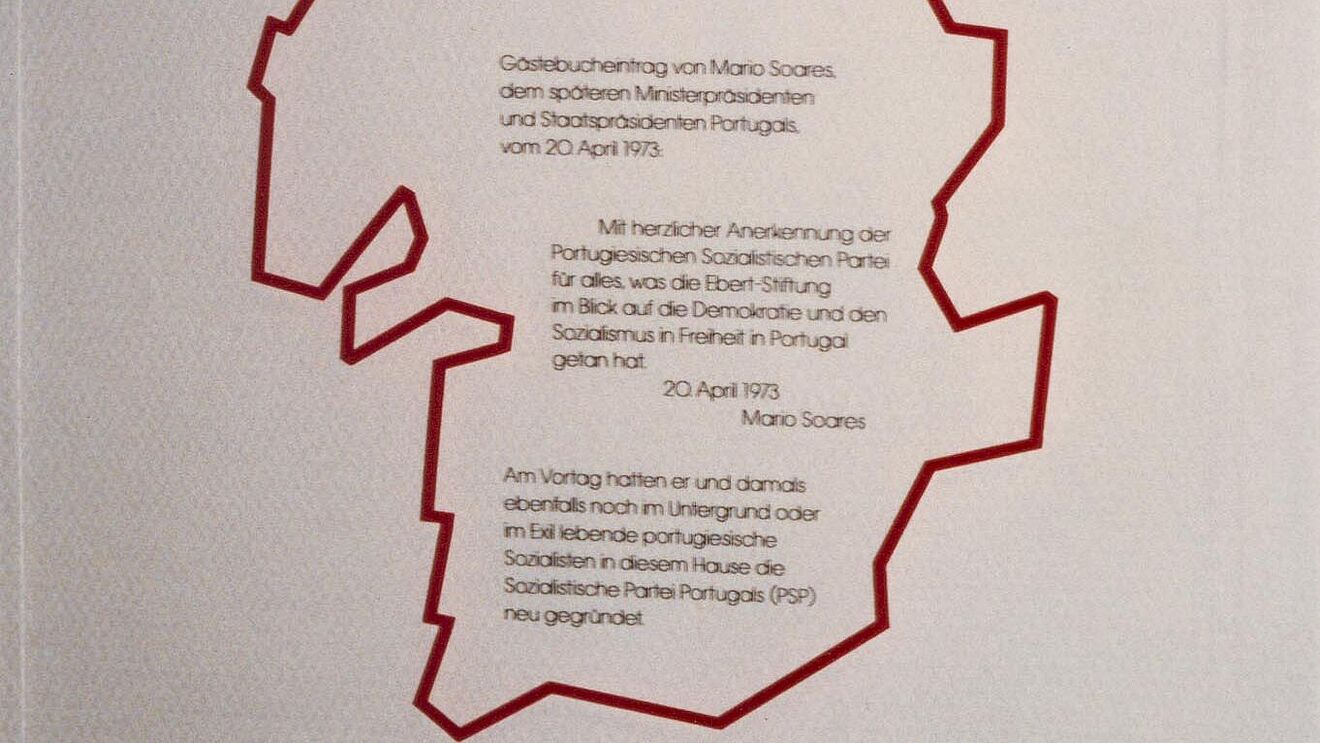

When Mário Soares first made contact with the SPD in September 1966, no one could have expected that the most important international partner for the democratisation of Portugal had been found. For, at first, the liaison between German social democracy and the socialist opposition in the Estado Novo did not appear to be very promising. Willy Brandt – who had been in government as Vice-Chancellor and Foreign Minister since 1966 – did not consider it feasible to change the course of the bilateral relations with the “New State”, despite the knowledge of a burgeoning socialist opposition inside Portugal. Instead, the SPD relied on backchannel diplomacy. While pursuit of the official foreign policy course continued until the fall of the Estado Novo, the party-affiliated FES was to establish contact with the group around Soares in order to support the Portuguese comrades of Socialist Action (ASP). A case in point was the re-founding of the newspaper República in 1970. The evident culmination of this approach was the founding of the Socialist Party (PS) on 19th April 1973 at a closed meeting in Bad Münstereifel near Bonn.

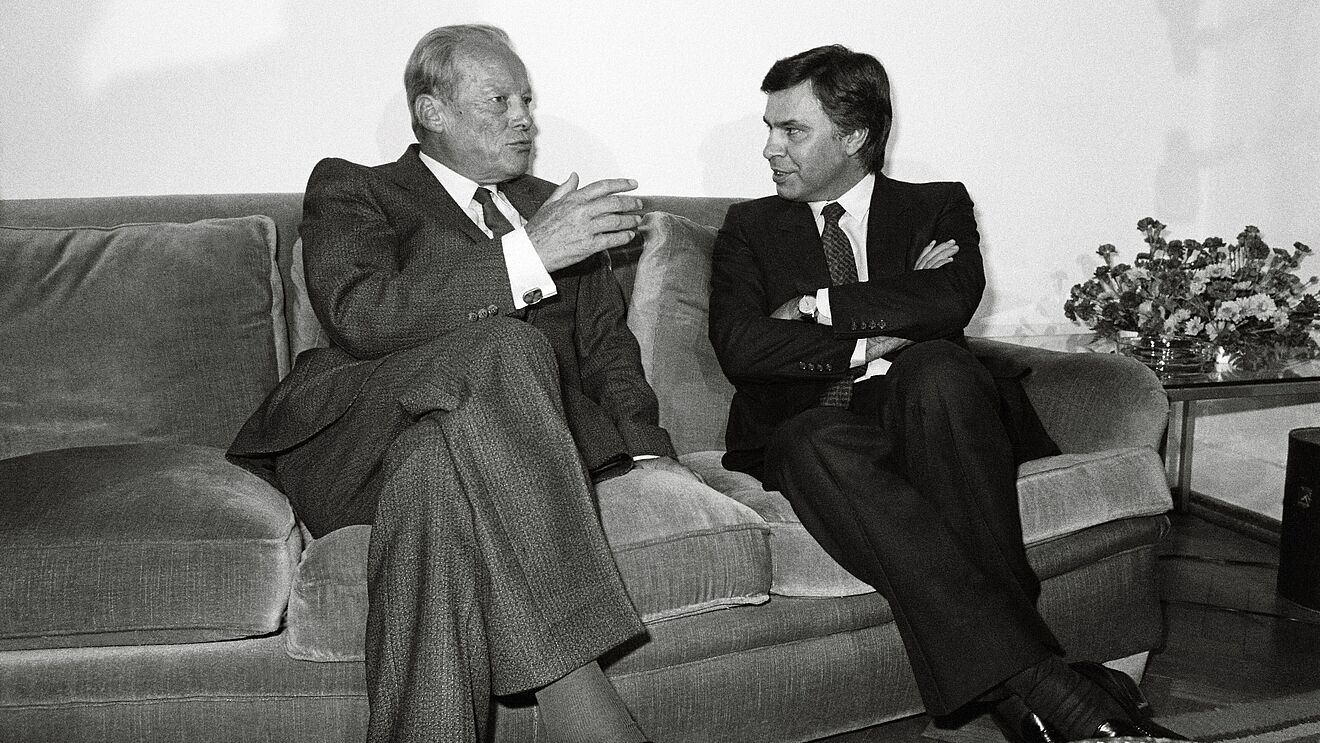

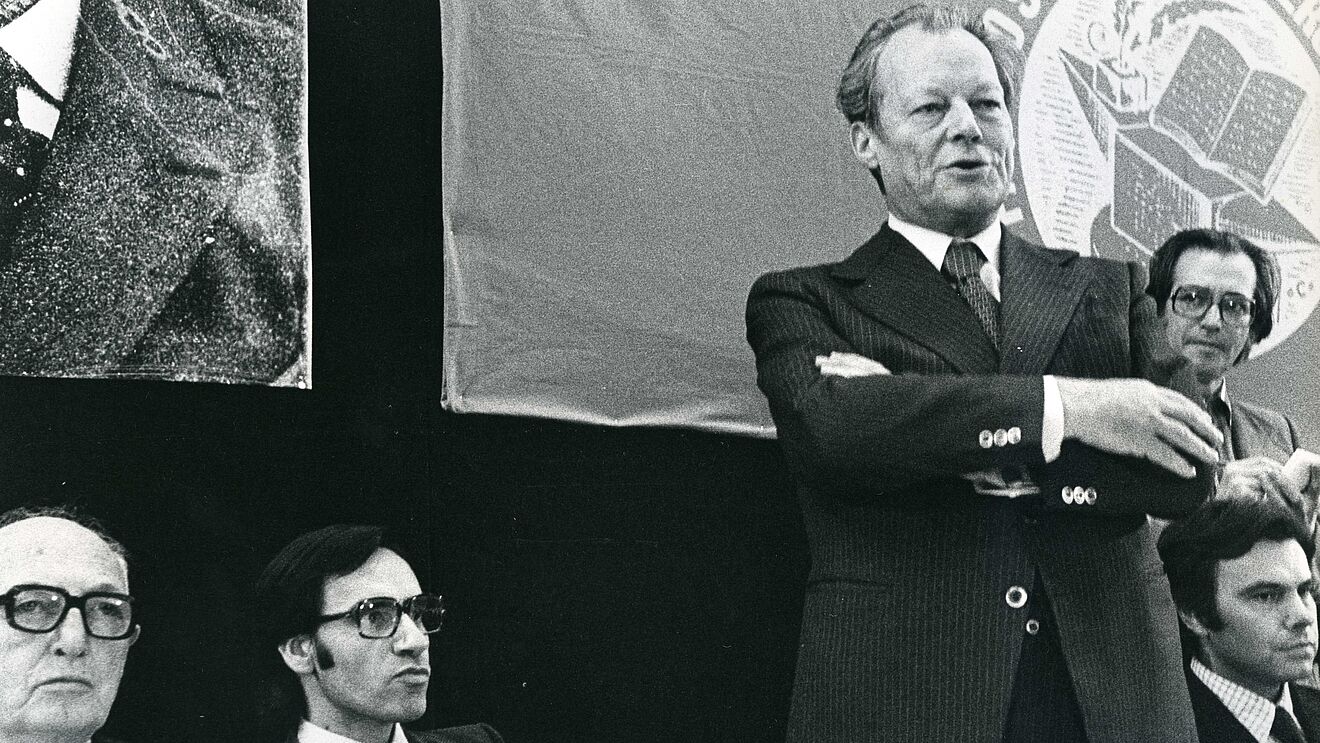

The Carnation Revolution ushered in the most intensive phase of cooperation between the SPD and the PS. The partnership can be divided into two main lines. Firstly, the evident structural weaknesses of the PS in Portugal had to be remedied. To this end, the FES provided direct financial support for the development of its political infrastructure and the establishment of party offices. The FES also transferred important know-how to the political cadre of the PS and thus contributed to sharpening the party’s political profile, which was to be formulated in demarcation to the Communist Party (PCP). Secondly, the SPD party leadership – first and foremost Willy Brandt – demonstrated solidarity with its Portuguese comrades. Through official visits to Portugal and the chairmanship of the “Committee for Friendship and Solidarity with Democracy and Socialism in Portugal”, Brandt signalled the strong support that the Portuguese Socialists enjoyed from their European sister parties.

The April elections of 1975 and 1976 saw the PS emerge as the strongest party in Portugal on both occasions with over 30% of the vote. In the light of this electoral success and the gradual democratic consolidation in Portugal, the SPD and FES continued their joint efforts. Their initial aim was to end the PCP’s monopoly over the trade unions. For this purpose, a think-tank was set up in 1977, the José Fontana Foundation, which was generously subsidised by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) via the FES. In 1979, the PS finally gained hegemony over the trade unions in a close alliance with the Social Democratic Party (PSD). The BMZ also provided start-up funding of 2 million DM – naturally through the mediation of the FES – for the PS’s most important municipal policy project, the Centre for Municipal Studies and Regional Action (CEMAR). In a centrally governed country like Portugal, political infrastructures had to be built up, especially in the isolated rural periphery.

Cooperation between German Social Democrats and the Spanish Socialist Party

The German Social Democratic Party (SPD) played a decisive role in helping the Spanish Socialists of the PSOE, weakened by 40 years of Francoist dictatorship, to become a reliable governing party within the space of a few years.

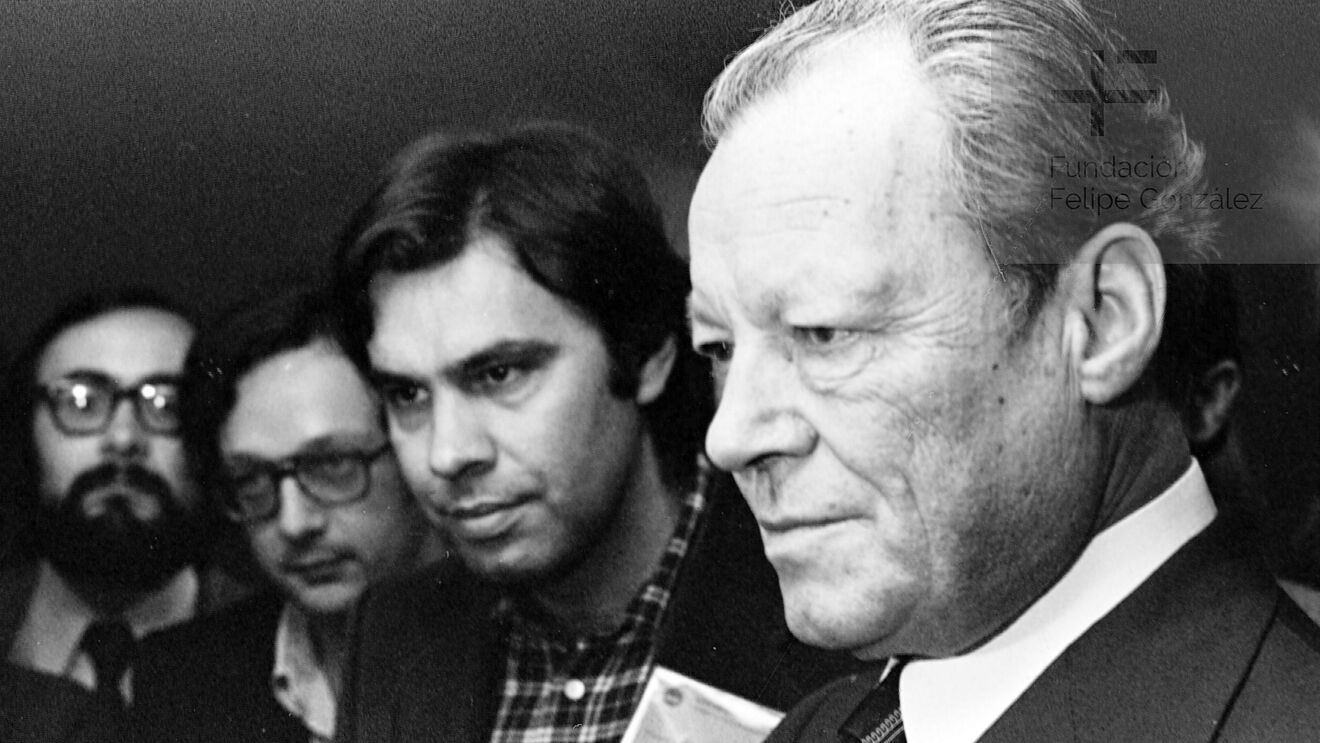

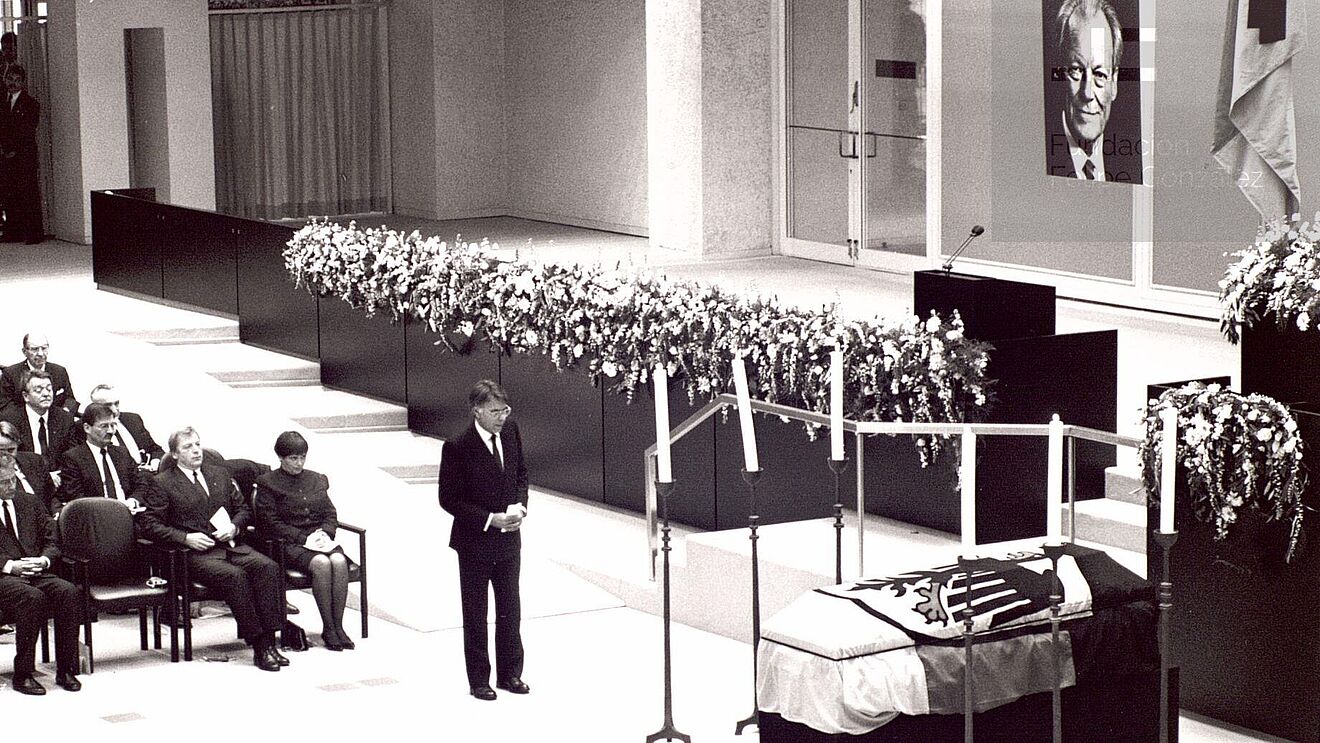

With an "Adiós, amigo Willy," Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González bid farewell to Willy Brandt at the former German chancellor’s state funeral in 1992. Brandt had also been president of the Socialist International (SI) from 1976 until his death. Indeed, the Spanish Socialists owed much to their friends from the German SPD. Their defeat in the Civil War had driven the Spanish Left into exile. Spain's oldest labor party, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), founded in 1879, was led from Toulouse by General Secretary Rodolfo Llopis after the conclusion of World War II. If the SPD had initially taken a radical anti-Franco course after the founding of the Federal Republic and supported the exiled PSOE, the German Social Democrats' policy toward Spain changed during the 1960s. After a trip to Spain by Deputy Chairman Fritz Erler in April 1965, the SPD moved closer to the domestic Spanish resistance, embodied first and foremost by the suspended university professor Enrique Tierno Galván and his Socialist Party of the Interior (PSI), founded in 1968.

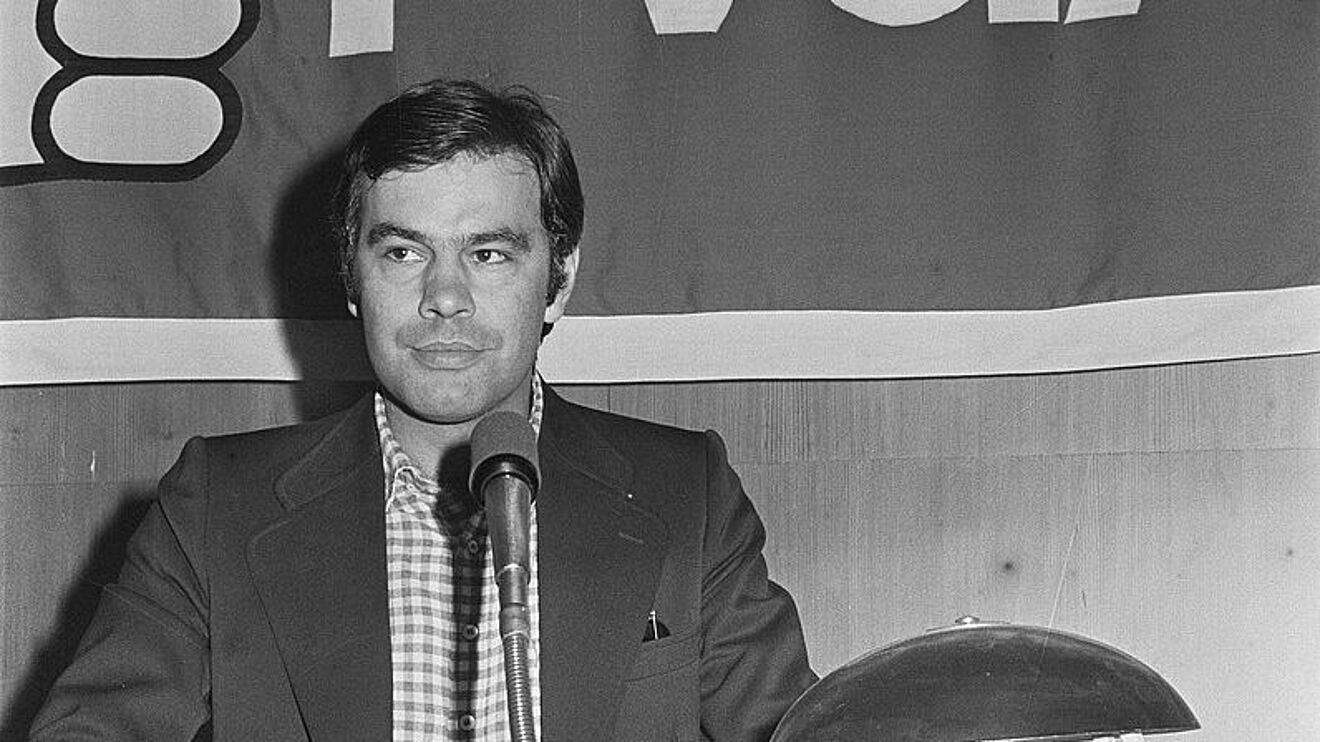

However, following the election of the reform-minded young lawyer Felipe González as the new Secretary General at the 1974 PSOE party congress in Suresnes, France, the SPD threw its weight behind the rejuvenated PSOE again. After Franco's death, the PSOE evolved as a strong alternative to the conservative-liberal Union of the Democratic Center (UCD) of Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez, which had won the first free Spanish elections in December 1977. The close friendship between Felipe González and Willy Brandt, who had participated in the Spanish Civil War as a war correspondent, strengthened the PSOE. Cooperation between the SPD and PSOE in the form of training and financial support enabled the establishment of party structures at both local and state levels. The most important coordination center became the Madrid office of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES), which opened in 1976 under the direction of Dieter Koniecki. After the Socialists' rather disappointing performance in the 1979 elections, the PSOE won an absolute majority three years later.

The year 1982 marked a shift in the balance of power in German-Spanish social democracy. While the Socialists triumphed in Spain and Felipe González was elected Prime Minister, in Germany Chancellor Helmut Schmidt's social-liberal coalition collapsed. The friendly relationship between González and his new German counterpart Helmut Kohl of the CDU weakened the SPD's position in Spain. In 1984, when suspicions arose that the FES had transferred funds from the German Flick conglomerate to the PSOE government in Spain in order to gain political advantage, the Spanish Socialists saw fit to distance themselves from the SPD. Nevertheless, the Spanish Socialists followed the opposition work of their German comrades with great attention. The Irsee draft for a new SPD basic program in 1986 was thus positively received. After German reunification, the Spanish Socialists stayed true to their moderate line, which had been shaped by the SPD, insofar as they rejected any advances made by the successors to the state party of East German Communism, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS).