History Curriculum in Spain

It took a long time before Franco's death in 1975 was recognized as a caesura in Spanish history classes. Up to this day, the Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship remain sensitive topics that are taught in as neutral and non-judgmental a fashion as possible – in the name of the societal consensus.

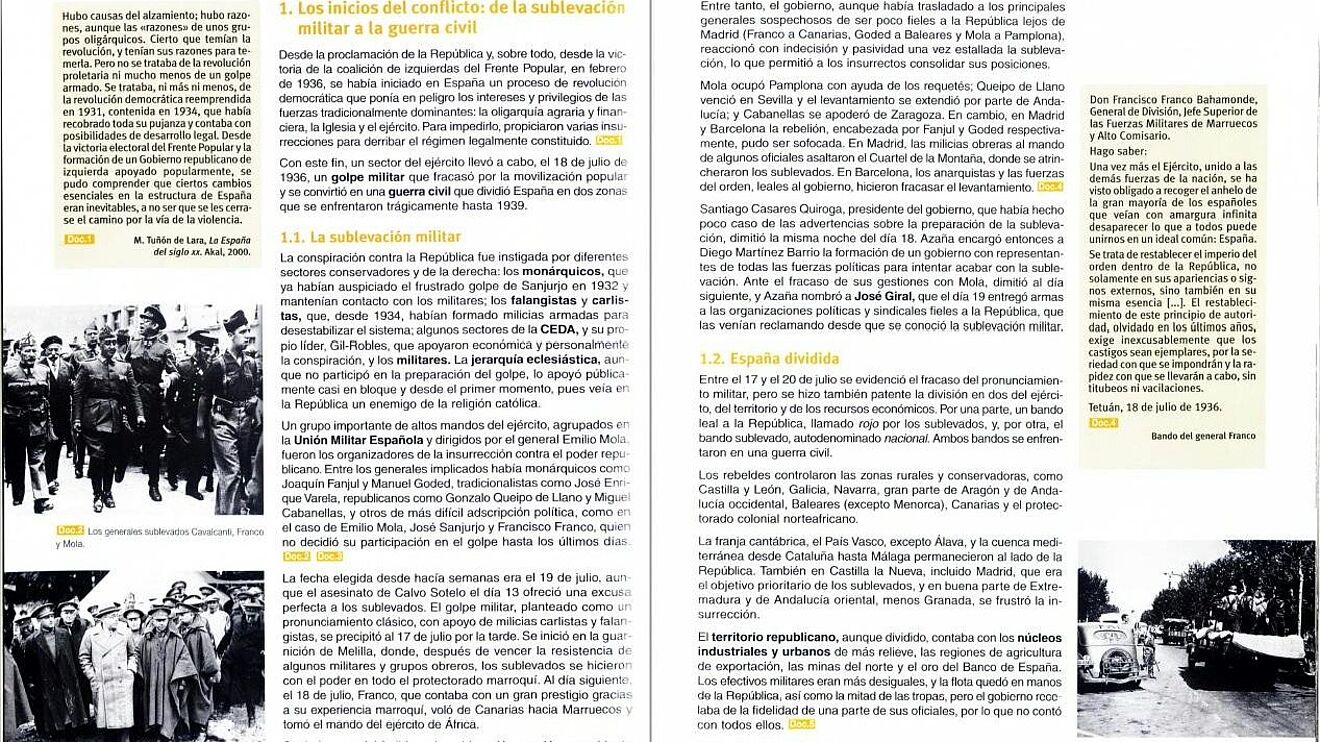

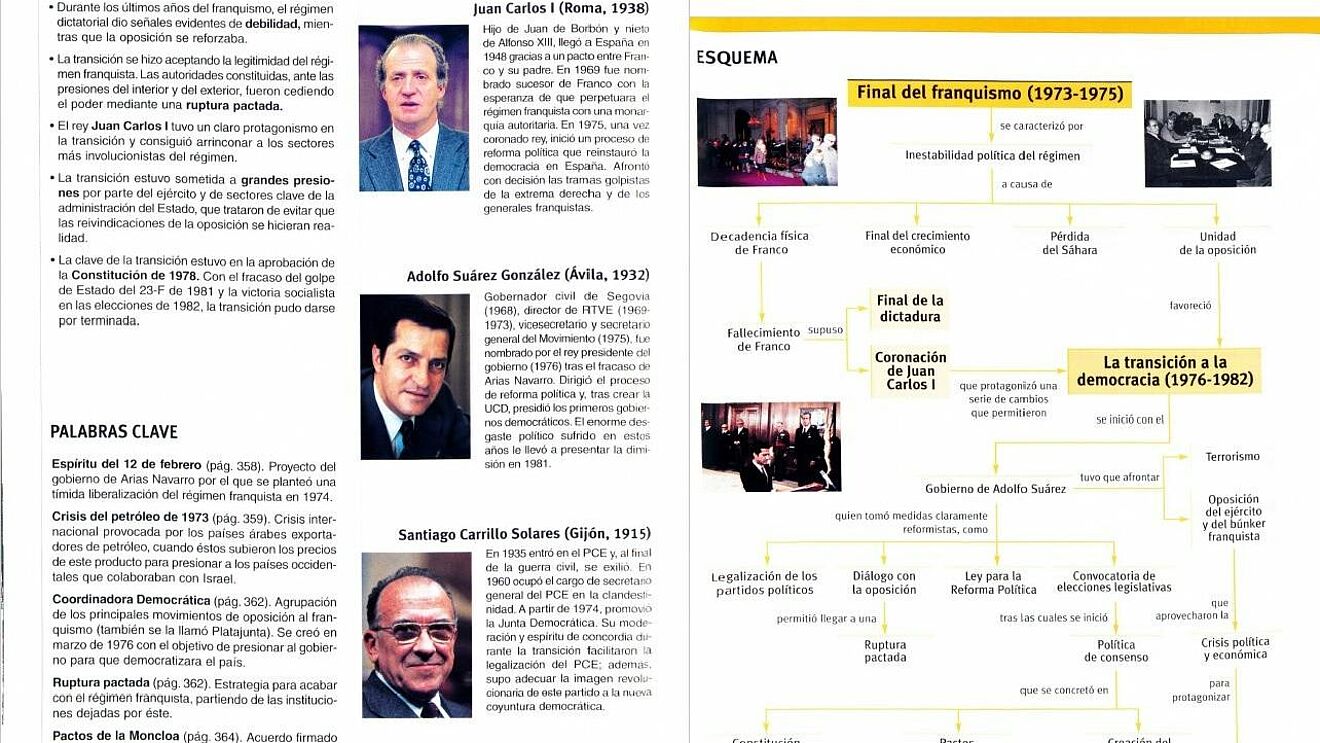

"The student should consider the democratic system as the most suitable for peaceful cohabitation and develop a positive attitude toward the constitution." In this frank manner, a 1983 draft underlined the democratic postulate of the PSOE’s educational reform, which was then not implemented until 1990. In the history lessons of those years, the democratic transition following 1975 was not yet taught as a clear caesura between dictatorship and democracy. Instead, Spanish textbooks included terms such as "economic development" and "social change," suggesting a gradual process of liberalization even during the dictatorship. It was not until the turn of the millennium that the Transición was conveyed as a political upheaval. Franco's dictatorship, however, is still often divided into the "bad" years of dearth after the Civil War and the "good" growth years of the 1960s. The Civil War is still treated in ambivalent terms. Thus, although the motivations of the 1936 coup are increasingly discussed, they are not normatively evaluated and judged.

Moreover, a peculiarity arises from the fact that, in Spain, history classes in middle school are traditionally divided into world history and national history, with the global contexts being taught first. This arrangement always allows Spain to be portrayed as a latecomer to the major European developments of the 19th and 20th centuries – bourgeois revolutions, industrialization and the labor movement, world wars, decolonization, and the Cold War. Rather than being able to shape such events, according to this determinist logic Spain would only feel their impacts. Following this notion, the Franco dictatorship is treated in world history merely as a side note to the European forms of fascism in Germany and Italy. In the higher grades, national history – in contrast to world history – is a compulsory subject. Given the wealth of topics covered in the final school year, however, it is left very much up to the teacher to decide how much space the Civil War and the Franco dictatorship actually occupy.

If Spain’s colonial conquests are taught within the framework of national history, the decolonization of the Spanish colonies in America remains a marginal note. Instead, the collapse of the British and French colonial empires tends to be taught in the framework of 20th century world history. Independent Latin America also reappears in the context of world history, with the continent's extremes – the Cuban Revolution, Perón's populism in Argentina and Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile – presented as negative counterexamples to the democratized and economically successful Spanish model. A completely different picture of Spanish history is presented in Catalan and Basque textbooks, where the "historical region" becomes the national frame of reference. The frontrunner position of the aforementioned regions as regards industrialization is emphasized. The Spanish Civil War is thus regarded as the defeat of the progressive autonomous regions by Franco's backward nationalist Spain.

History Curriculum in Portugal

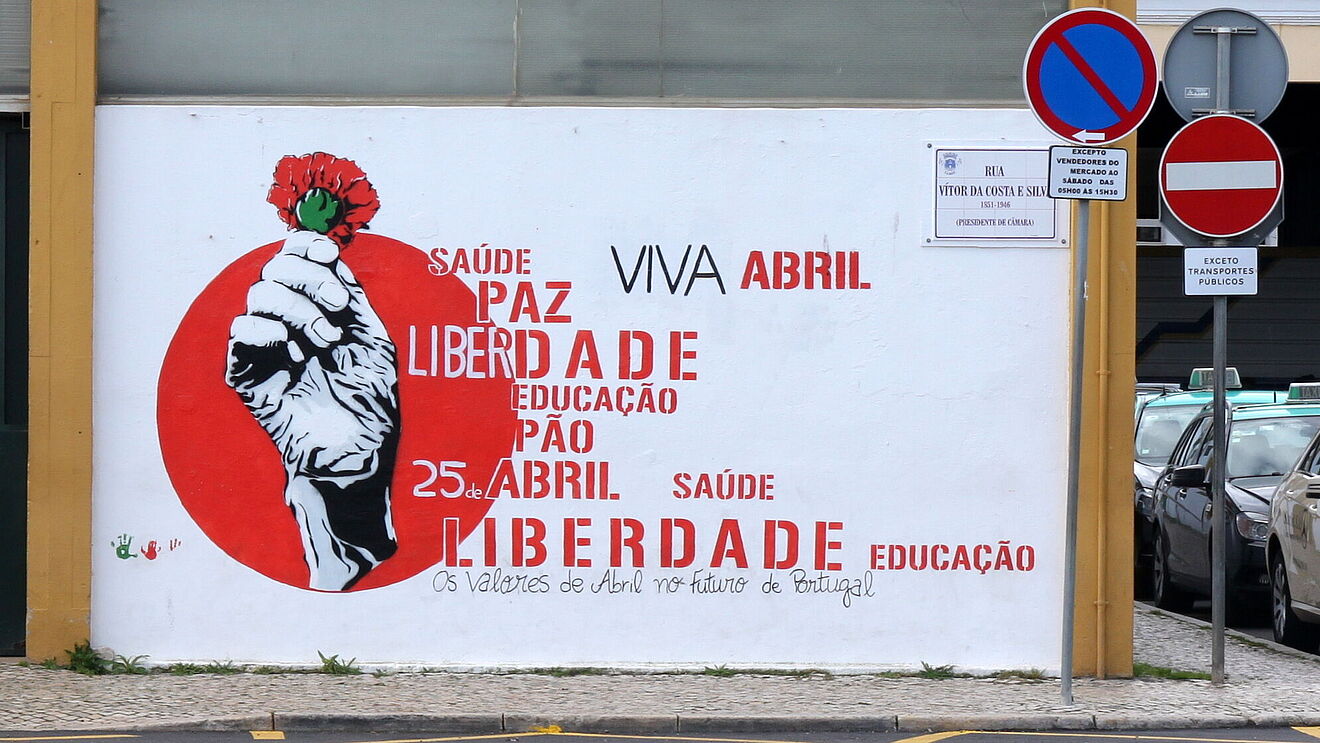

In the past 50 years, Portuguese history teaching has undergone various paradigm shifts. During the period of revolutionary transition (1974–1976), the total rejection of the former dictatorship was the focus of interest. Nowadays, the aim of history teaching is to provide the students with an increasingly global view of the past.

“The pedagogical movement is intimately linked to the political one”. These words were proclaimed in a pamphlet printed by the MFA in the midst of the revolutionary process in 1975. Accordingly, it indicates that, with the political break, a revision of the education system – branded as “fascist” – was already being forced. The fierce political polarisation, especially during the “hot summer” of 1975, which was accompanied by a temporary dominance of left-wing political forces in Portugal, was also reflected in the teaching of history. Textbooks of the time feature hagiographic representations of Lenin and equate Salazarism with Nazism. Furthermore, pupils are confronted by politically tendentious questions such as “What are the crimes of capitalism”?

With the gradual democratic consolidation from 1976 onwards, revolutionary passions disappeared from the history books. Topics such as the Portuguese Colonial Wars began to gain in importance at the turn of the 1970s and on into the 1980s. What is also striking is the dominance of primary sources in the history books of that era. Since the 1990s, a clear typological distinction between Salazarism and other forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism in Europe has prevailed. At the turn of the millennium and onwards, clear convergences with the European culture of remembrance have become visible, marked by the inclusion of Holocaust remembrance as well as intensified postcolonial criticism.

“A new chapter in history”. This is how the renowned publisher Porto Editora introduces its educational materials, divided into three volumes, for the teaching of twelfth-grade history in Portugal. The paradigm shift in history teaching in contemporary Portugal is marked by a watershed in the choice of topics. The third volume of the presented series deals exclusively with transnational and international topics. For instance, it focuses on the history of the European Union, which has become a growing reference point in the country’s political life since Portugal’s accession to the EU on 1st January 1986. Recent historical events and the new multilateral forums in the Lusophone and Ibero-American world are treated in similar detail. These include the UN mission during the East Timor conflict, the handover of Macau to China, the founding of the CPLP on 17th July 1996 and the Ibero-American summits.