Spain at the Ibero-American Summits

The end of the Franco regime marked a reorientation of Spanish foreign policy. In addition to Europeanization and NATO membership, improving relations with Latin America was also on the agenda. This shift became manifest at the Ibero-American summits, starting in 1991.

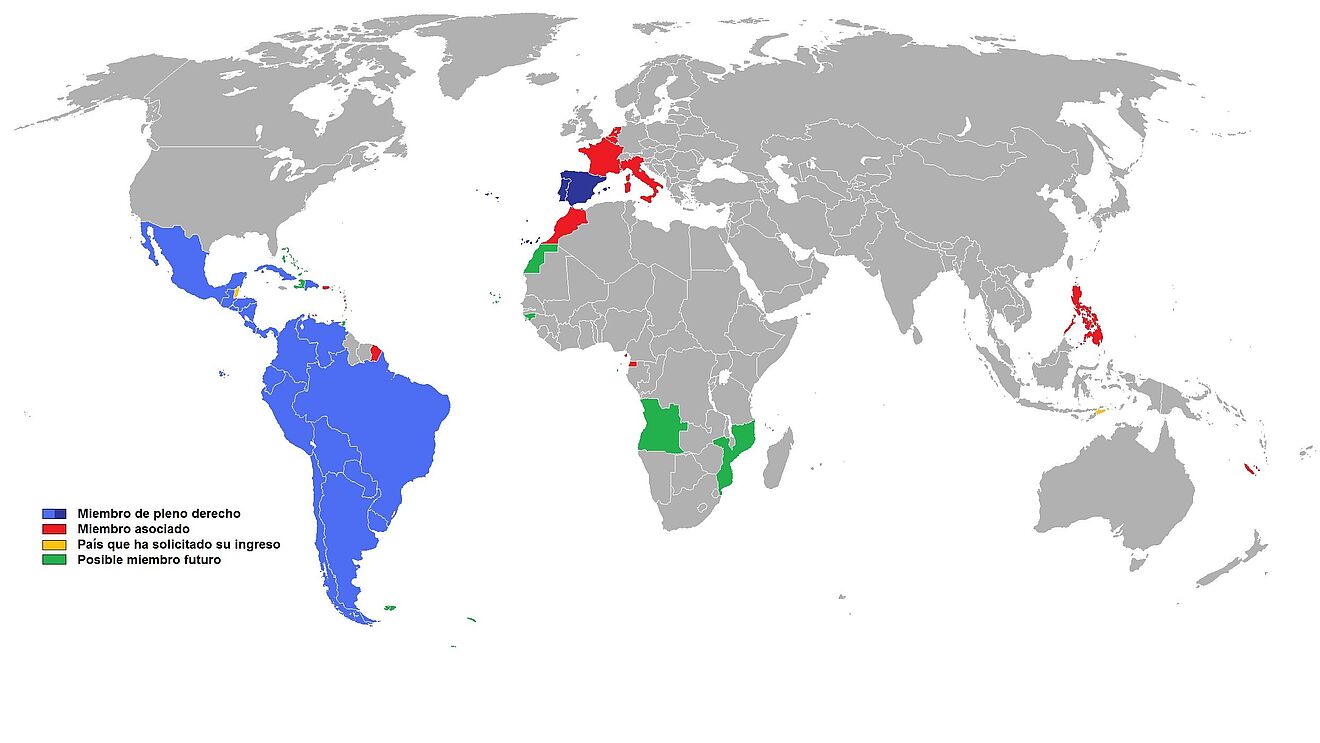

"Overall, it can be said that during colonization, individual and collective rights were violated in such a way that, from today's perspective, constitutes a violation of the laws of both nations." In 2019, on the 500th anniversary of the conquest of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City) by a Spanish army, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador demanded an apology from the Spanish royal family in an open letter. Traditionally, the mother country's relations with its former Latin American colonies have been ambivalent. Nonetheless, post-Transición Spain sought rapprochement after the end of Latin American dictatorships in the late 1980s. If Felipe González had already traveled to dictatorial Chile as opposition leader in 1977 and campaigned for the release of socialist lawyer Erich Schnake, as Spanish Prime Minister, together with Mexican President Salinas de Gortari, he initiated the Ibero-American summits held annually from 1991 onward with the heads of state and government of Spain, Portugal and the 19 countries of Latin America attending.

Within this forum, Spain had a model function in terms of democratization and economic development. A counter-image and enemy image cultivated above all in the Spanish news media was Cuban President Fidel Castro. By dint of his authoritarian autocracy of more than 30 years and the economic backwardness of his country, Castro embodied everything that Spain believed to have overcome. At the same time, it was possible to revive old communist enemy images from the Franco era and to reassure Spain of its civilizational advantage. After the Viña del Mar summit in 1996, El País proudly announced that Castro had signed a declaration committing himself to pluralism and democracy, thus making concessions to the democratic mainstream. On the other hand, a horrified reaction ensued when the Cuban caudillo refused to jointly condemn ETA at the Panama Summit in 2000. In this way, the balance of power between Spain and Cuba provided an indication of the degree of democratization in Latin America as well as underlining the role of the Iberian mother country as a schoolmaster.

The extent to which Spain was vulnerable to criticism within this international forum was demonstrated at the 1998 Porto summit, when Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar and the presidents of Argentina and Chile, Carlos Menem and Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, signed a communiqué emphasizing the primacy of national jurisdiction over international law that explicitly condemned the actions of Spanish investigating judge Baltasar Garzón in the arrest of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London. Spain's Western ties in the North Atlantic defense alliance also ran counter to Latin American interests at times. Symptomatic of this was Spain's accession to NATO in 1982, which took place at the very moment when its new ally, Great Britain, was at war with Argentina over the Falkland Islands. In particular, the paradigmatic shift from Felipe González's laissez-faire policy to José María Aznar’s loyalty to Washington from 1996 onward led to lasting disagreements. In this respect, the declining participation of Latin American heads of state at Ibero-American summits from the 2000s onward is symptomatic of a deterioration in Ibero-American relations.

Portugal's Cooperation with the Former Colonies

It was to take two decades before a forum of cooperation between Portugal, Brazil and the former African colonies could emerge from the ruins of a devastating colonial war.

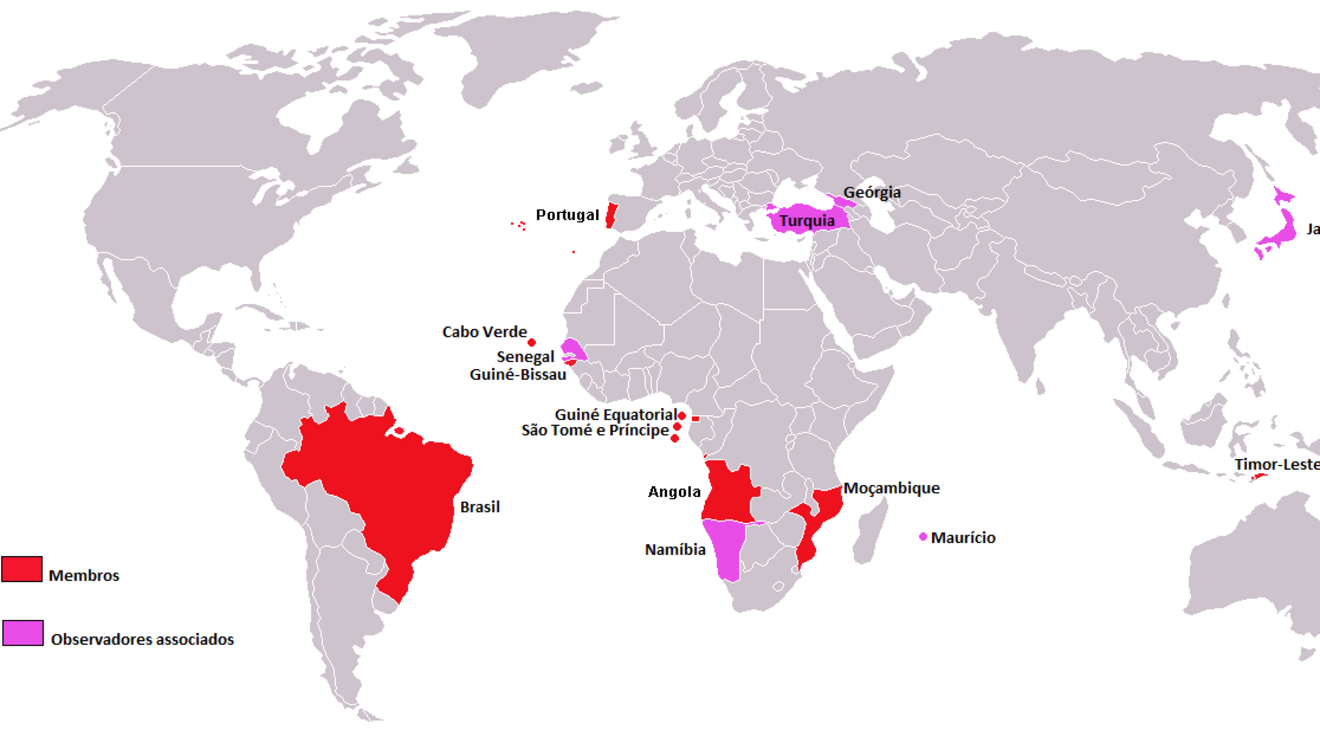

The Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP) was founded on 17th July 1996. It was initially composed of the founding members Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe, with East Timor joining subsequently in 2002 and Equatorial Guinea in 2014. The CPLP is the most important multilateral forum in the Lusophone world, which discusses and develops the programme of cooperation at biennial summits. From the seventh summit on 25th July 2008 onwards, which was entitled “The Portuguese Language: A Common Heritage, a Common Future”, there has been an increasing rapprochement in cultural cooperation between the participating countries. This is reflected, for example, in the “Portuguese Language and Culture Day within the CPLP”, introduced on 5th May 2009. UNESCO later designated this as the “International World Portuguese Language Day” in 2019.

The major step for the normative framework of the CPLP was taken in May 2013, when the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were declared as the basis for joint action within the community. In addition to political and economic cooperation, the CPLP is thus now also moving closer together as a community of values. Due to its post-colonial constellation, this community of values is burdened by a problematic shared history. Consequently, the inevitable question must be asked: Will the new transnational framework serve to re-examine the past together, or will a cloak of silence be spread over the conflicting memories?

“Memory is one of the most fundamental elements in the construction of identities, from the most local to the most transnational one. The [...] CPLP, an institution whose foundation goes back to the common history of the countries that belong to it, cannot be indifferent to the question of memory and its preservation." This call for a transnational culture of memory among the Lusophone countries was made by Cátia Miriam Costa and Olivia Pestana in 2018 at a meeting on cooperation between archives and national libraries within the CPLP. That the historical memory of the CPLP member states should become a fundamental axis of cooperation was already decided in 2017 at the tenth meeting of the CPLP ministers of culture. Both positive and negative aspects of shared memory are to receive attention. Important elements for coming to terms with the negative aspects of the past are certainly the shared experiences of dictatorship and the Portuguese Colonial Wars.