Memory Literature in Portugal

José Saramago, António Lobo Antunes and Lídia Jorge are among the most decisive figures in the literary reappraisal of Portugal’s troubled aspects of its past. Even before the archives relating to the dictatorship and the Colonial War could be opened, they helped to recover the memory of past atrocities.

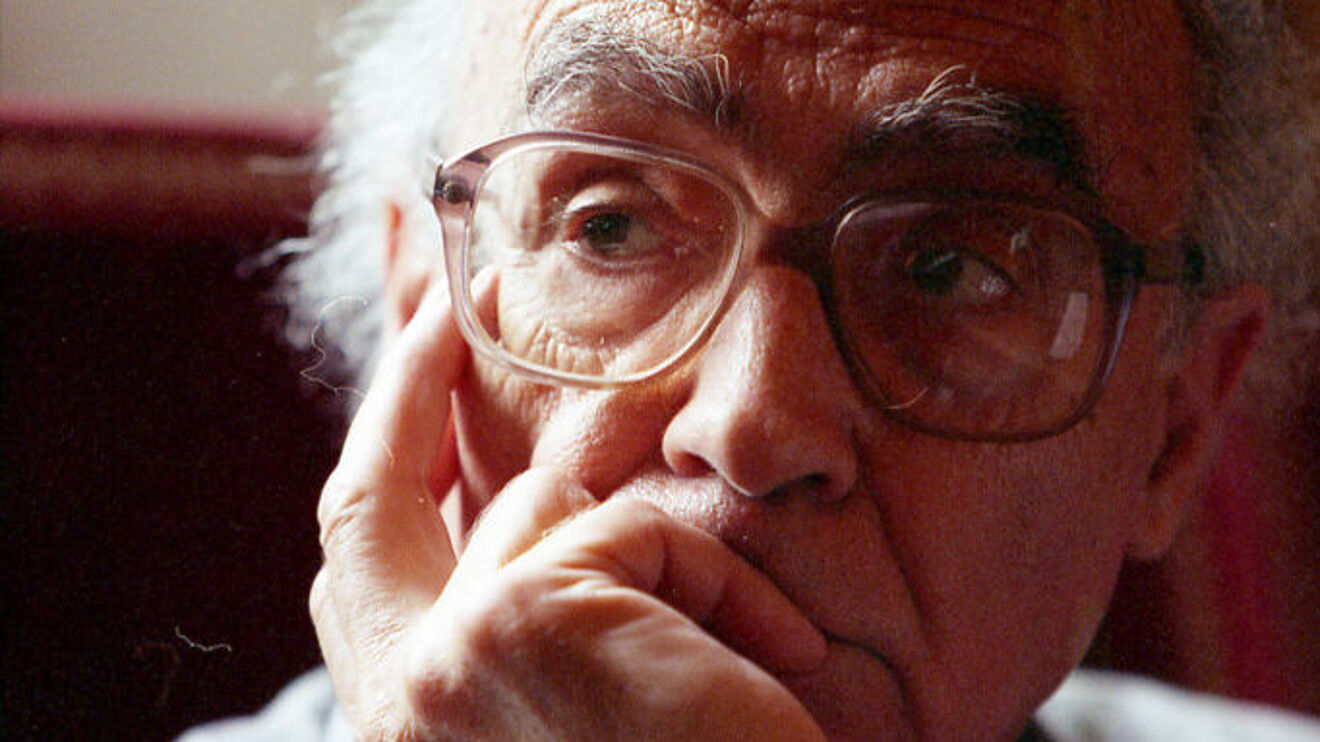

José Saramago, born in 1922 into poor conditions in the village of Azinhaga in the Ribatejo region, remained a convinced communist all his life. In 1998, he became the only Portuguese to date to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. His life in opposition to the Estado Novo and the Catholic Church had a particular impact on his literary oeuvre. As a man of conviction, Saramago did not content himself with the mere remembrance of the Portuguese dictatorship in his novels. Indeed, his early work is driven by a militant activism. In Levantado do Chão (1980), he describes the generation-spanning misery of the Alentejan rural population in a “history from below” that, at the end of the work, revolts against its masters in the Carnation Revolution. In O Ano da Morte de Ricardo Reis (1984), Saramago castigates the passivity of the Pessoan heteronym Ricardo Reis during the fascisation of Europe in the mid-1930s. Saramago’s historiographical metafiction reaches its climax in the novel Memorial do Convento (1982), in which the author draws historical parallels between the construction of the National Palace of Mafra by João V and the inauguration of the Estado Novo by Salazar. The undoubted merit of this pugnacious intellectual can be seen in his efforts to create awareness of the often-neglected Portuguese dictatorship on an international stage.

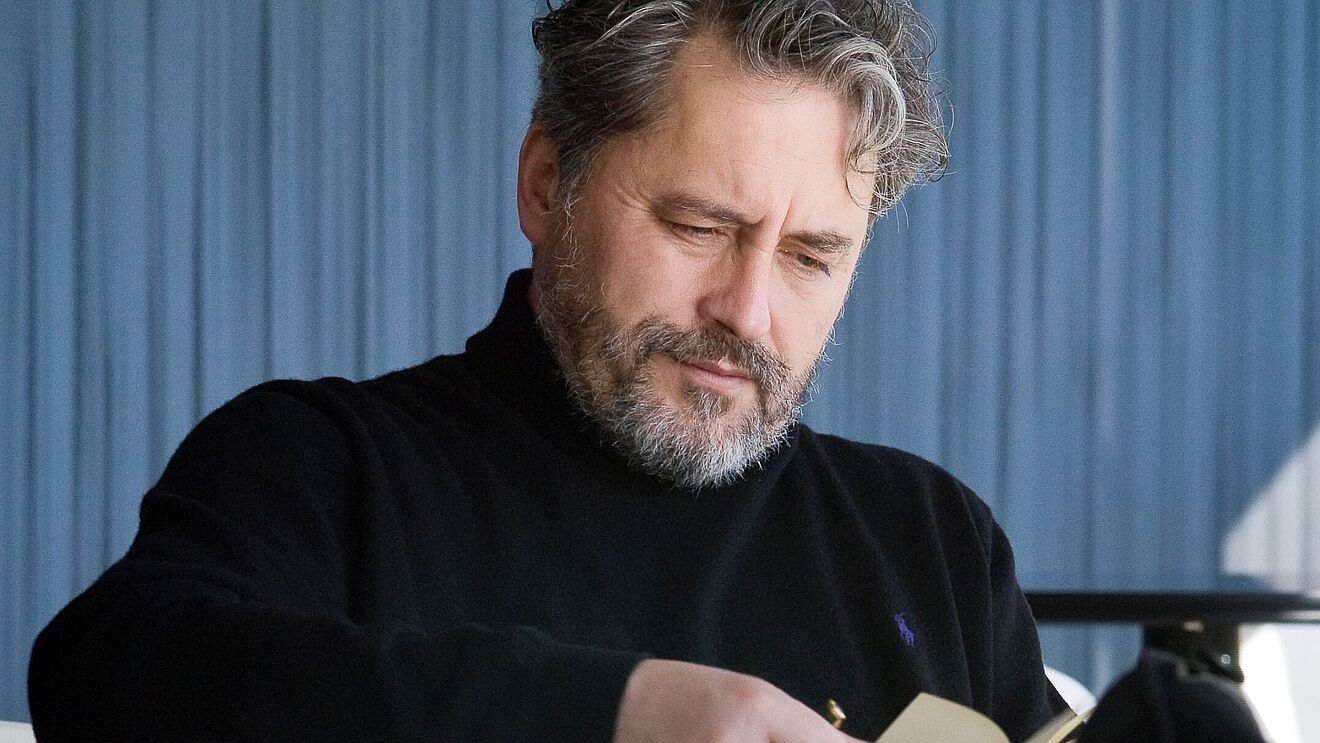

António Lobo Antunes, the “writing conscience of a scarred nation” (Kilanowski), is the author who has dealt most intensively with problematic aspects of the Portuguese past in his oeuvre, which has grown to more than thirty novels. Although he was born into an aristocratic family in Lisbon in 1942 – and thus privileged in the Estado Novo – Lobo Antunes had to serve as a medical officer in the Colonial War in Angola from 1971 onwards. In his autobiographical debut trilogy – Mémoria de Elefante (1979), Os Cus de Judas (1979) and Conhecimento do Inferno (1980) – Lobo Antunes works through the traumas of the Colonial War in chilling detail. Numerous novels about the pathologies of the Salazar dictatorship followed, such as Manual dos Inquisidores (1996). As a postmodern writer, he deconstructed the self-image of Portugal as the nation of discoveries in As Naus (1988) and provided a disillusioned view of the Carnation Revolution in Fado Alexandrino (1983).

Lídia Jorge is one of the most important authors of the literary reappraisal of the colonial past and the Carnation Revolution in contemporary Portugal. Born in Boliqueime, Algarve, in 1946, she, like António Lobo Antunes, belongs to the 1940s generation. Both experienced the Colonial War and the Carnation Revolution intensely. As an officer’s wife, Lídia Jorge was caught up twice in the theatre of war: first in Angola (1968–1970) and later in Mozambique (1972–1974). She impressively describes her experiences in Mozambique in A Costa dos Murmúrios (1988), in which the atrocities committed by the Portuguese army almost reach genocidal proportions. The novels O Dia dos Prodígios (1980) and Os Memoráveis (2014) both address the Carnation Revolution but reflect it in very different ways. In the first novel, the Carnation Revolution is told from the perspective of a small village in the Portuguese periphery. In the latter, a Portuguese reporter from Washington returns to her home country in 2004 to reappraise the Carnation Revolution in retrospect through interviews with contemporary witnesses.

Memory Literature in Spain

The literary treatment of the recent Spanish past is primarily defined by a persisting fascination with the Civil War. The ideals, conflicts, and victims of these intense and painful three years form the core of such narrative reflections.

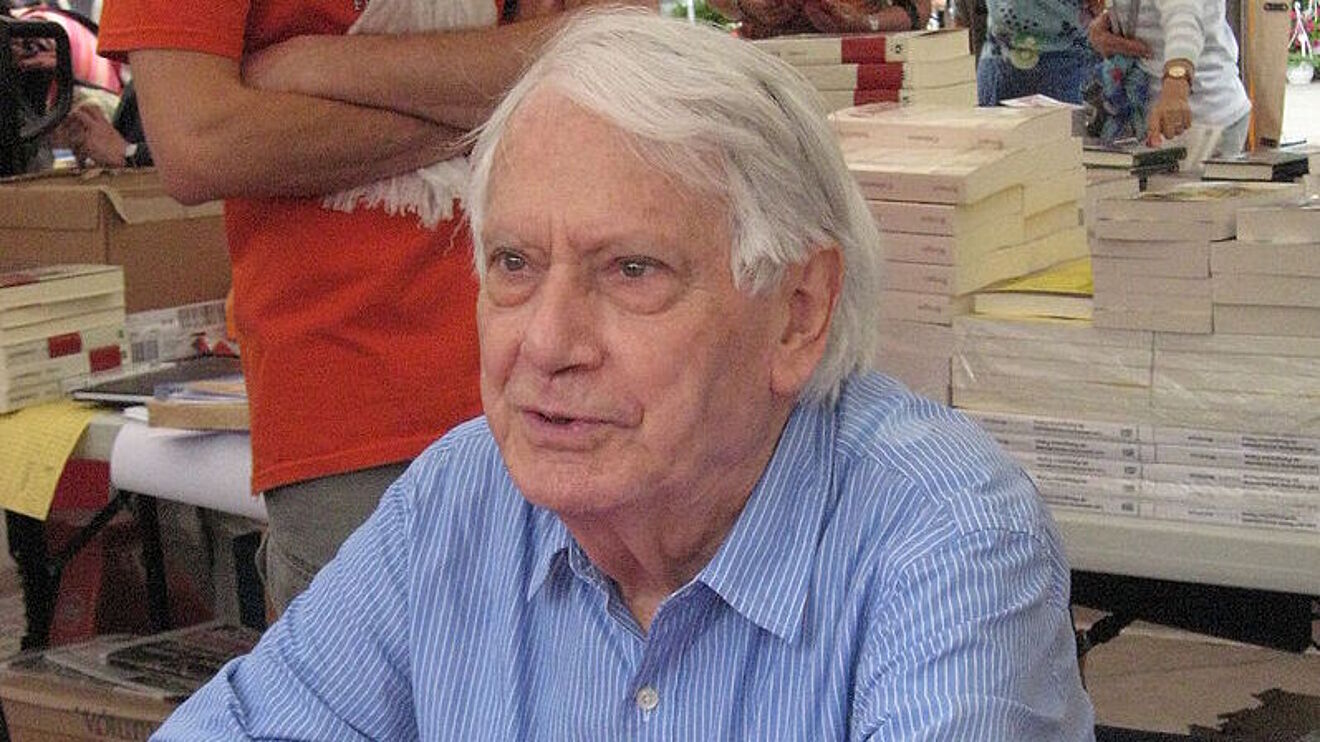

Fighter of the French Resistance. Survivor of Buchenwald concentration camp. Member of the Central Committee of the Spanish Communist Party. Advocate of a moderate Eurocommunism, which prompted his expulsion from the party in 1964. Non-partisan Minister of Culture in the PSOE cabinet of Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González. Jorge Semprún, born in Madrid in 1923, experienced the age of extremes first-hand more closely than almost any other figure. Based on his own eventful life, the intellectual produced a rich literary oeuvre. The best known of his novels are the accounts of his time in Buchenwald, Le grand voyage (1963) and Quel beau dimanche (1980), works full of poetic tragedy. In his Autobiografia de Federico Sánchez (1977) and the subsequent works Federico Sánchez vous salue bien (1993), Le mort qu'il faut (2001) and Veinte años y un día (2003), he dealt with the traumatic losses of the Civil War and the price of the Transición using his old pseudonym. In 2003, he spoke at the annual commemoration of the Victims of National Socialism in the German Bundestag.

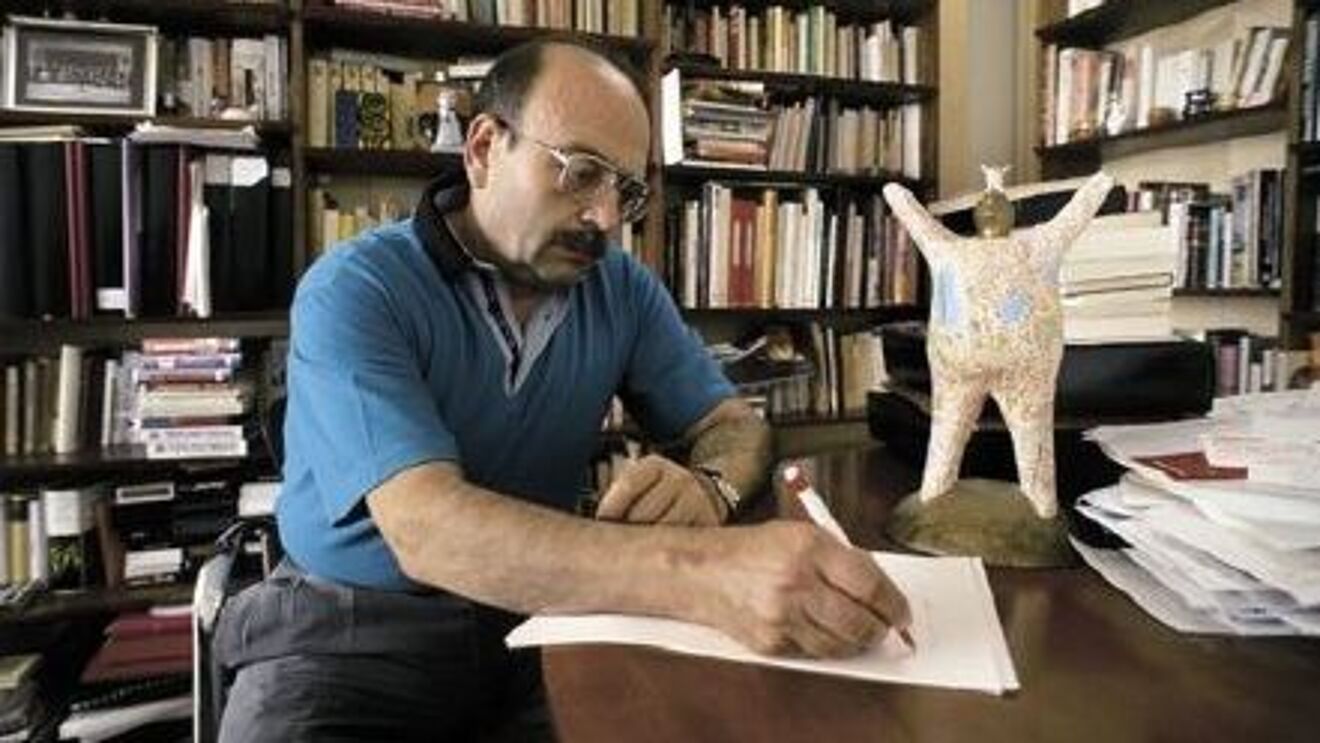

If Semprún belonged to the generation that had experienced the Civil War and Franco's dictatorship first-hand, Javier Cercas (*1962) is probably one of the most distinguished literary exponents of the post-Franco generation. Both parents had sided with the nationalists in the Civil War: a fact that would haunt Cercas. A doctor of philology, Cercas had his literary breakthrough with the novel Soldados de Salamina (2001), in which his main character conducts research into a founder of the fascist Falange party, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, shedding light on the moral gray areas of the final phase of the Civil War and the ideals of that era’s lost generation. Soldados de Salamina, a bestseller which shifted more than a million copies, is a factual novel mixing interviews with diary entries as well as source analysis with reflections on the reliability of memories. Cercas remained true to this literary hyperrealism in Anatomia de un instante (2009) and El monarca de las sombras (2017), in which he dealt with the 1981 coup and his own family history respectively.

The most important contemporary voice from the victims’ perspective is, however, Almudena Grandes (*1960), who died in 2021 and dedicated her six-part novel cycle Episodios de una guerra interminable to the resistance against the Franco regime. Her mostly female main characters dedicate their lives to a struggle lasting for years and usually ending in loss, torture, and death. Throughout, real events serve as a basis – such as the 1944 invasion of the Valley of Arán by guerrilla fighters previously exiled in France in Inés y la alegría (2010), the Spanish escape network of German Nazis to Argentina in Los pacientes del doctor García (2017), and the martyrdom of feminist Aurora Rodríguez Carballeira in 1950s Franco-era Spain in La madre de Frankenstein (2020). Like Cercas, Grandes was a regular author of a column in El País. In addition, the staunch republican was at times politically active for the left-wing alliance United Left. The last novel in her Episodios de una guerra interminable about those going into hiding during the Civil War (topos), Mariano en el Bidasoa, remains inconclusive.