Public Holidays and Commemorative Days in Portugal

After the fall of the dictatorship, the origins of the Republic were commemorated in democratic Portugal, the traditional patriotic holidays were reinterpreted transnationally, and 25th April was established as the founding myth of Portugal’s emergent democracy.

On the Avenida da Liberdade in Lisbon, the chants of a large crowd resound: “Forever 25th April – Fascism never again!”. Red carnations can be seen everywhere – it is 25th April, Freedom Day in Portugal. The national celebrations commemorate 25th April 1974, when the dictatorship in Portugal was overthrown by young officers. Instead of a violent escalation, the officers received red carnations from the population. These became the eponymous symbol of the Carnation Revolution. The memory of the revolution developed into the linchpin of the democratic culture of remembrance in Portugal, turning 25th April into the country’s most important public holiday. Since 1977, the Portuguese parliament has also celebrated the festivities with speeches by the president, the prime minister and delegates of the parties represented in parliament. The major daily and weekly newspapers are filled with interviews with contemporary witnesses, and the country’s intellectuals debate the dictatorial past as well as the legacy of the Carnation Revolution.

A more traditional holiday that can be associated with a democratic culture of remembrance in Portugal is 5th October – the day of the establishment of the Republic. The commemorations on this day remember the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the First Republic on 5th October 1910. Even during Salazar’s “New State”, 5th October remained a national holiday because the illusion of the Republican state was to be maintained, at least nominally. In practice, the political police PIDE used the celebrations to identify and dismantle republican networks. With the overthrow of the dictatorship on 25th April 1974, the meaning of 5th October reverted back to its original emphasis. The First Republic was now to be declared the cradle of Portuguese democracy, upon whose legacy post-dictatorial Portugal could build. Since then, 5th October has been celebrated in the capital accompanied by a military parade including national symbols such as the national flag and the Portuguese national anthem. The solemn ceremony is concluded by speeches from the President of the Republic and the Mayor of Lisbon. In 2012, the public holidays on 5th October were suspended. Only four years later, however, this controversial decision was revoked once again.

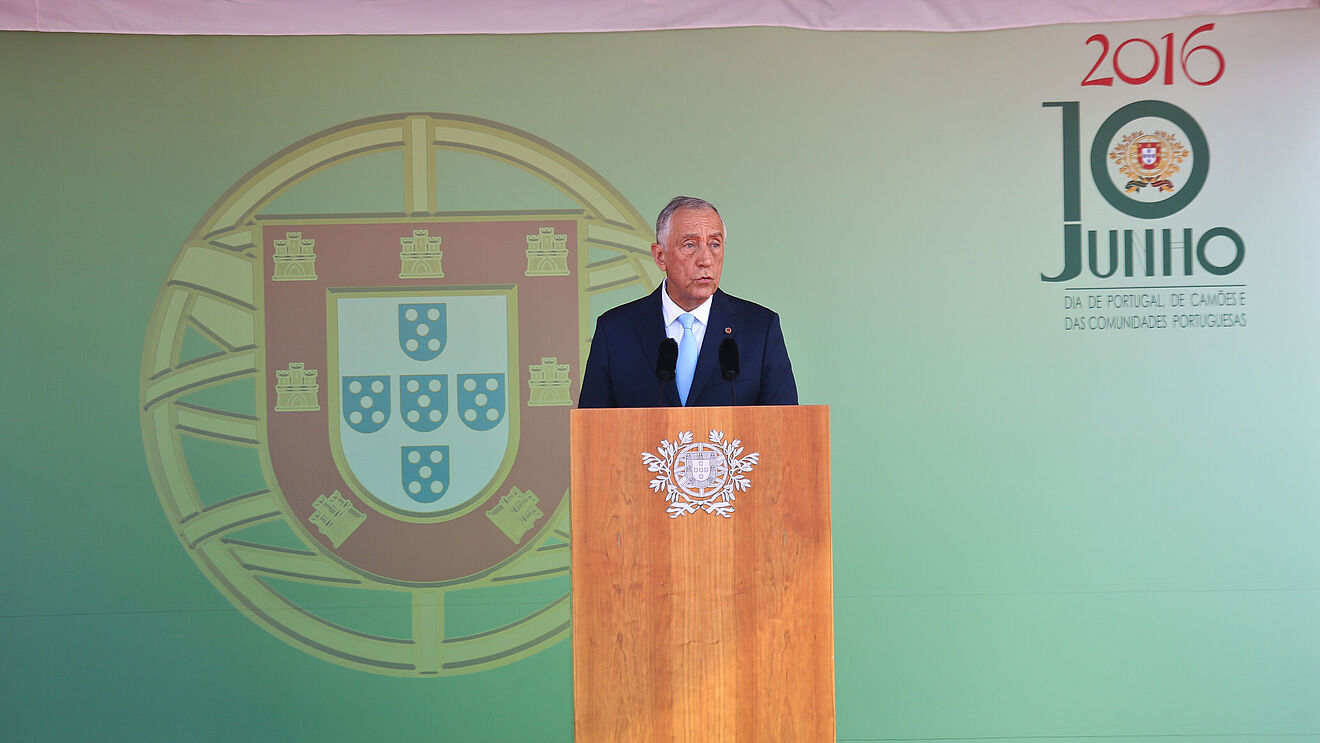

Unlike the aforementioned commemorations, 10th June as a public holiday is not a commemorative pillar for democracy in Portugal. 10th June was solemnly introduced in 1880 and thus dates back to the Portuguese monarchy. This day commemorated national poet Luís Vaz de Camões, who is said to have died on 10th June 1580. With the honouring of Camões, a monument was simultaneously erected to the Portuguese language, which was perfected in Camões’ epic Os Lusíadas. This also indicates the clearly patriotic character of the holiday, which later took on an ethnic-chauvinist intensification in the Estado Novo through the epithet “Day of the [Portuguese] Race”. The democratic transition and decolonisation from 1974 onwards made the reinterpretation of the public holidays urgently necessary. Eventually, 10th June was renamed “Day of Portugal, Camões’ and the Portuguese Communities” in 1978. The increasing departure from the national fixation is also reflected in the transnationalisation of the commemoration. Henceforth, 10th June was celebrated in both a Portuguese city and a centre of the Portuguese diaspora – for example, in Paris in 2016, and in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro the following year.

Public Holidays and Commemorative Days in Spain

While the central days of commemoration prevalent during the Franco dictatorship were reinterpreted and abolished after 1975, newly instated and reintroduced national and regional holidays brought a high degree of potential for political conflict to the table.

Stretching 480 kilometers, a human chain transversed the autonomous region of Catalonia on September 11, 2013. This "road to independence" was initiated to underline Barcelona's demands for independence. The day was chosen intentionally. Commemorating the conquest of Barcelona in the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, the Diada de Catalunya, Catalonia's national holiday, had been banned with the capture of Barcelona by Franco's troops in February 1939. Reinstated in 1976, it has been the central reference point for the Catalan independence movement, especially since 2010. In the Basque Country, in addition to the traditional national holiday of Aberri Eguna (Day of the Fatherland) on Easter Sunday, April 26 also became a day to commemorate the 1937 bombing of Guernica, with special reports appearing in El Correo de Bilbao on each major anniversary. In 1997, ETA declared April 26 a "day of struggle," killing a policeman and calling for resistance against Madrid's centralism.

At the national level, the dictatorial calendar of holidays had to be reinterpreted in democratic terms after Franco’s death in 1975. July 18, the day of the 1936 military coup d'état, became the foremost day of commemoration of the Civil War and its victims, primarily in the form of newspaper articles. On the one hand, on the 50th anniversary on July 18, 1986, Prime Minister Felipe González warned that the Civil War was "not an event to be commemorated." On the other hand, a series of articles entitled "La Guerra de España" appeared simultaneously in the daily newspaper El País, in which Spanish historians commented on individual aspects of the Civil War. On April 1, "Victory Day" of the nationalists in 1939, Franco had always reviewed a military parade in Madrid. From 1977, this event was held in alternating cities in early summer as "Armed Forces Day" under the direction of the King. Especially in its early stages, this day was highly conflictual. ETA even killed four military personnel and two police officers in addition to carrying out a bombing in Madrid around the Armed Forces Day of 1979. On November 20, the anniversary of Franco's death, those nostalgic for the dictatorship regularly marched in the "Valley of the Fallen" until this was banned in 2007.

On December 6, 1983 – the fifth anniversary of the adoption of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 – the "Day of the Constitution" was established for the first time. At the initial ceremony in Parliament, King Juan Carlos gave a positive assessment and spoke of the "cement of living together in peace and freedom." From the turn of the millennium, the constitution came under increasing criticism. Leading Spanish politicians and legal scholars spoke out in favor of reform in the 30th anniversary issue of El País in 2008. Spain's central "national holiday," October 12, celebrated since 1892 and commemorating Columbus' landing in America in 1492, underwent an ongoing revision. While Franco's dictatorship celebrated Spain's imperial superiority on what was then called "Day of the Race," after 1975 the holiday was dedicated to international understanding. The Spanish royal couple thus met with Mexican President López Portillo on the Canary Islands on October 12, 1977. On the 500th anniversary of Columbus' landing on October 12, 1992, King Juan Carlos closed the Seville Expo with a message of friendship to the countries of Latin America.