Portugal: The Salazar Era (1933-1968)

For over 30 years, the introverted Salazar imposed his will on Portugal. While he was able to navigate the country smoothly through the Second World War, the regime ultimately failed due to Salazar’s unwillingness to grant independence to the African colonies.

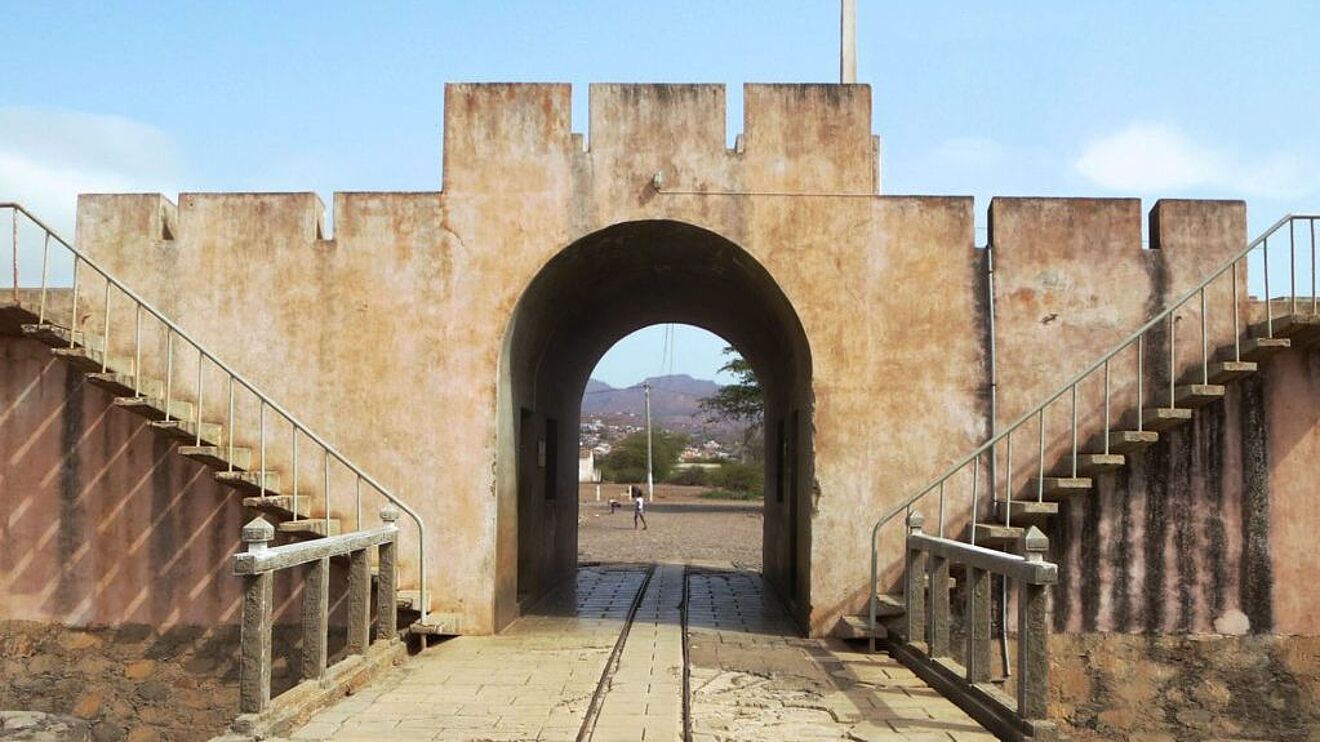

The essence of the Estado Novo can be summed up in Salazar’s obsession with hierarchy and order, which was also reflected in the state institutions. Pluralistic competition was eliminated by a single party, the National Union. The various social bodies such as the Church, universities, the trade unions and even family were incorporated into a single chamber of estates. Undesired opinions were eradicated by censorship. Finally, opposition members were imprisoned, tortured and in rare cases murdered by the newly created political police, the PIDE. The death toll was limited to 50 victims in almost 50 years of dictatorship. However, the total number of almost 30.000 political prisoners and the severe detention conditions in the Tarrafal concentration camp on Cape Verde shed light on the repressive nature of the regime. The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), founded in 1921, represented the most persistent opposition to the dictatorship and therefore also suffered the most severe political persecution.

In terms of foreign policy, Salazar navigated the Estado Novo through the Second World War, in which Portugal officially remained “neutral”, but supported both the Allies by providing air bases in the Azores and Nazi Germany through tungsten trade. To ensure the continuation of the Estado Novo in the post-war period, the concept of “organic democracy” was introduced as a self-characterisation, as it had been in neighbouring Francoist Spain, and mock elections were allowed. With the advent of the Cold War and Portugal’s accession to NATO as a founding member in 1949 and to the UN in 1955, the Estado Novo was finally able to emerge from international isolation. In the early 1960s, Salazar pursued a policy of opening up the country economically, albeit in a controlled fashion. He did this by joining the EFTA in 1960 and the OECD in 1961. Despite these measures, however, Portugal remained far behind the Western European standard of living at the time.

The first serious challenge to the Estado Novo was posed by General Humberto Delgado in the 1958 presidential election. He succeeded in mobilising the masses in a nationwide election campaign. Through electoral fraud, the election eventually went in favour of the regime. Humberto Delgado was assassinated by the PIDE in exile in Spain in 1965. The watershed finally came in 1961 – a genuine annus horribilis for the Estado Novo. In the colony of Angola, African liberation groups revolted against their Portuguese colonial rulers. The uprising, which was met with disproportionate use of force, marked the beginning of the Portuguese Colonial War which was to last for thirteen years. The war successively expanded to the African colonies of Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe and became the “Portuguese Vietnam”.

The "New State"... and its Victims (1939–1975)

For nearly 40 years, Francisco Franco controlled Spain's destiny – playing his political supporters off against each other and maintaining the order of the victors of the Civil War while gradually liberalizing the Spanish economy.

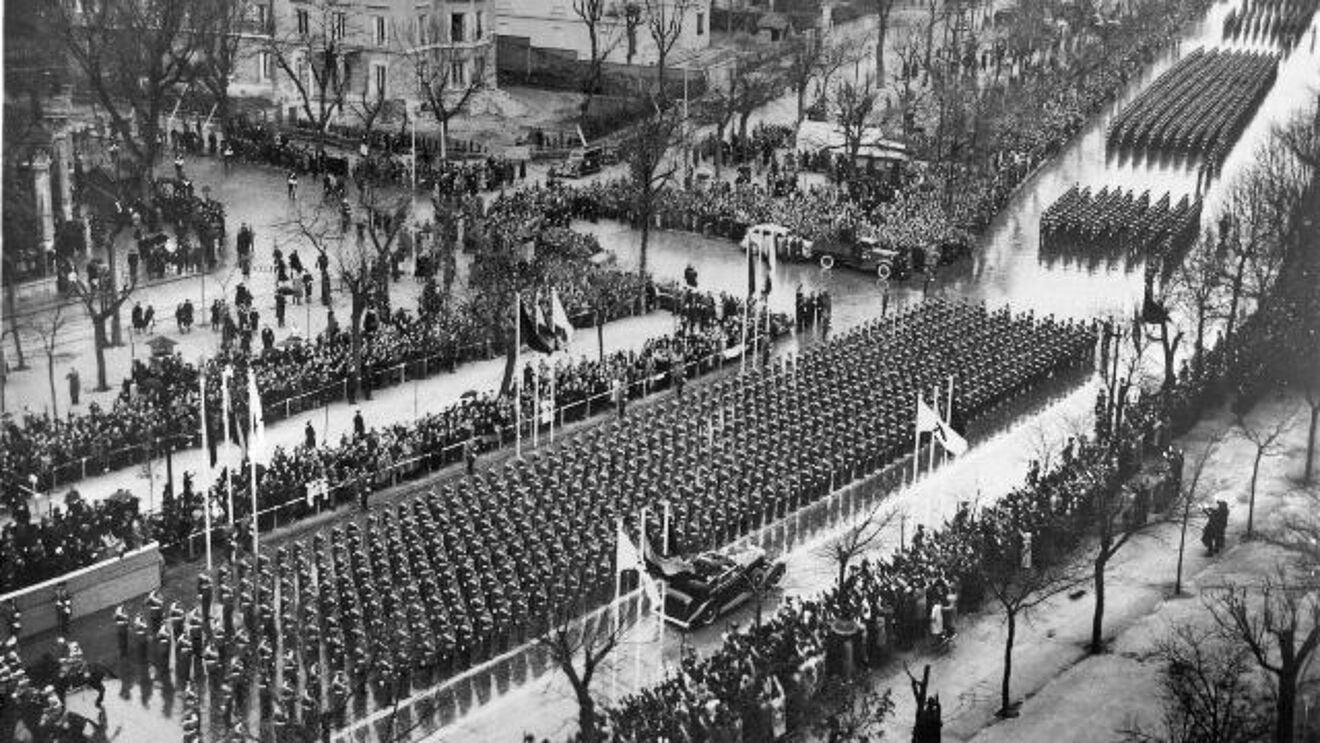

Through clever tactics, as well as the deaths of many political rivals, Francisco Franco had placed himself at the head of the insurgent military as the unrestricted Caudillo por la gracia de Dios ("leader by the grace of God"). He was to rule the country for 40 years, upholding the deep rift between the victors and the vanquished of the Civil War. The regime's catalog of enemies included everything that ran counter to the ideology of "eternal Spain," with its guidelines of nation, church, and family. Above all, internationalist-minded and progressive-thinking individuals came under constant fire: socialists, communists, anarchists, Freemasons, Protestants, atheists, and homosexuals were branded as "anti-Spaniards." Unlike in the Nazi state, Jews were less likely to be targeted by the state's inflammatory ideology. In this sense, the Catholic Church was a counterweight to the anti-Semitic Falange party. Within his regime, which political scientist Juan Linz described as "authoritarian" in distinction to democracy and totalitarianism, Franco skillfully played various groups of his supporters – fascist Falangists, conservative monarchists, devout Catholics – off against each other.

Internationally, Spain remained isolated after the end of World War II, which Franco had kept his country out of. Since the victorious Allied powers had no interest in cooperating with a dictator branded as fascist, Spain was not admitted to NATO, nor did it benefit from the economic support of the Marshall Plan. Economically, the 1940s in Spain were disastrous. The Civil War had destroyed the country’s infrastructure, and the vanquished of the Civil War had to work to a large extent as forced laborers under life-threatening conditions at the Guadalquivir Canal, in the Miranda de Ebro labor camp or on prestige projects such as the monument "The Valley of the Fallen." In total, an estimated 150,000 people lost their lives in the wave of post-war repression. Hardly any convinced republican, communist or socialist did not face permanent disadvantages in job allocation and pay in Franco's "New State."

After the end of World War II, Franco sought to project a moderate image of Spain as a conservative "beacon of the West" against Soviet communism. The United States now gradually relaxed its sanctions against the dictator. In 1953, Washington and Madrid concluded a military base agreement, in 1955 Spain was admitted to the United Nations, and in 1959 US President Eisenhower visited Madrid. In 1966, the "organic state law," a sham democratic constitution, divided the power between Franco as the head of state, a crown council appointed by him, and a rubber stamp parliament as the legislative chamber. With the cabinet reshuffle of 1957, Franco gave the starting signal for the economic opening of the country. Economic liberal experts and technocrats from the Catholic Opus Dei now took the initiative. The Stability Pact of 1959 opened the country to foreign currency. European tourists now flocked to a country in which political prisoners were still occasionally executed with the medieval-style choking iron (garrote vil).

Links

Sociologist David Casado Neira on the Forgotten Places of Postwar Repression (Spanish)

Webpage "Rotspanier" on Forced Labour and Detention Camps of Spanish Republicans (German)

Historian Pau Casanellas on Reistance against Franco in 1968 (English)

Historian Rafael Vallejo Pousada on Tourism during the Franco Dictatorship (Spanish)