Monuments and Topography in Portugal

Democracies also immortalise their heroes in statues and monuments. This statement is increasingly true for Portugal. The dictatorial legacy has been replaced by its adversaries and the symbols of the Carnation Revolution. The glorification of the country’s colonial heritage remains controversial.

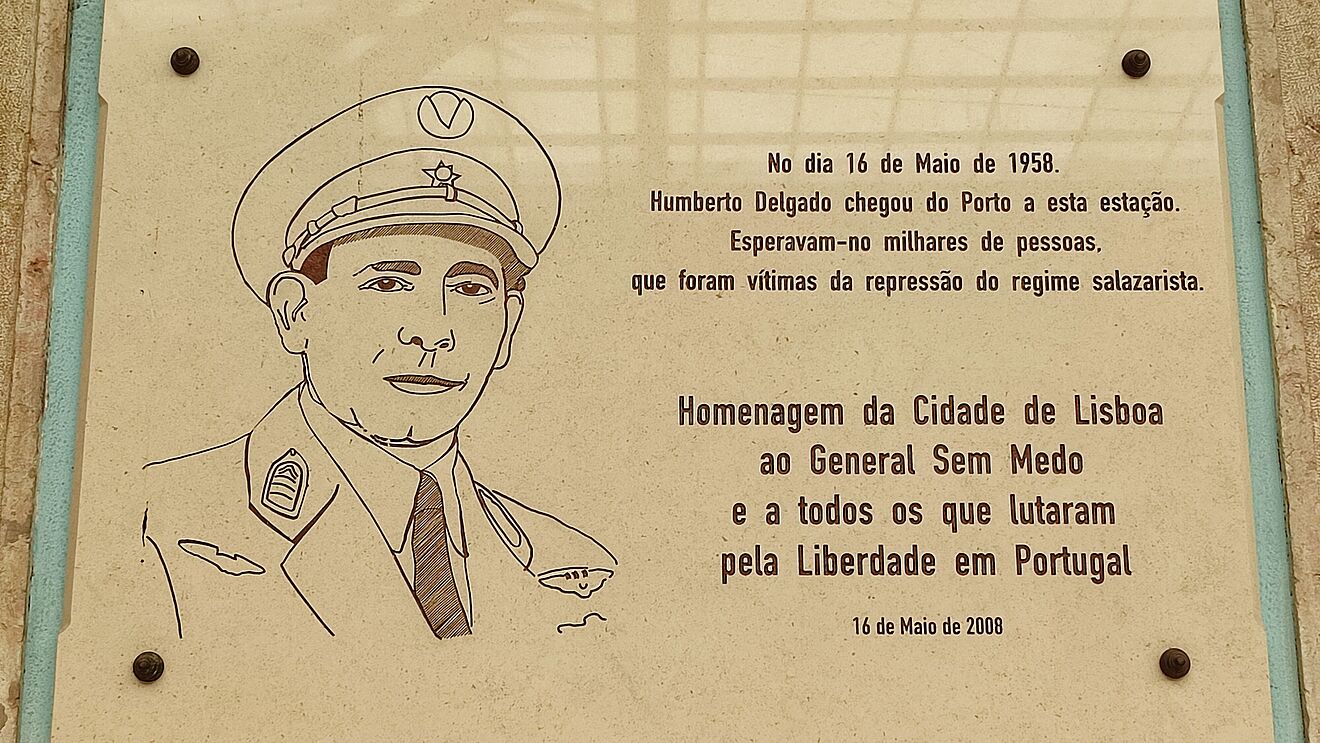

The heroes of Portuguese democracy today are chiefly those who opposed the dictatorship of the “New State”. The most prominent figure of the military resistance was Humberto Delgado, popularly known as the “general without fear” (general sem medo). In the 1958 presidential elections, he caused a serious crisis for the regime. His candidacy could only be stopped by electoral fraud. In Delgado’s birthplace, the small village of Boquilobo, a museum was set up in his honour and a statue erected next to it. The main road that runs through the village now bears his name, as does Lisbon airport. The presidential elections of 1958 brought forth another hero of the resistance, António Ferreira Gomes, who was Bishop of Oporto at the time. He paid for his criticism concerning the elections in particular and the lack of liberties in the Salazarist regime in general with exile in Spain. In Oporto, a statue of Ferreira Gomes was erected by Arlindo Rocha in 1979 in front of the Clérigos Tower. A prominent monument honouring opposition writers such as José Saramago and Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen was inaugurated in Coimbra – not far from the former PIDE headquarters – in 2001.

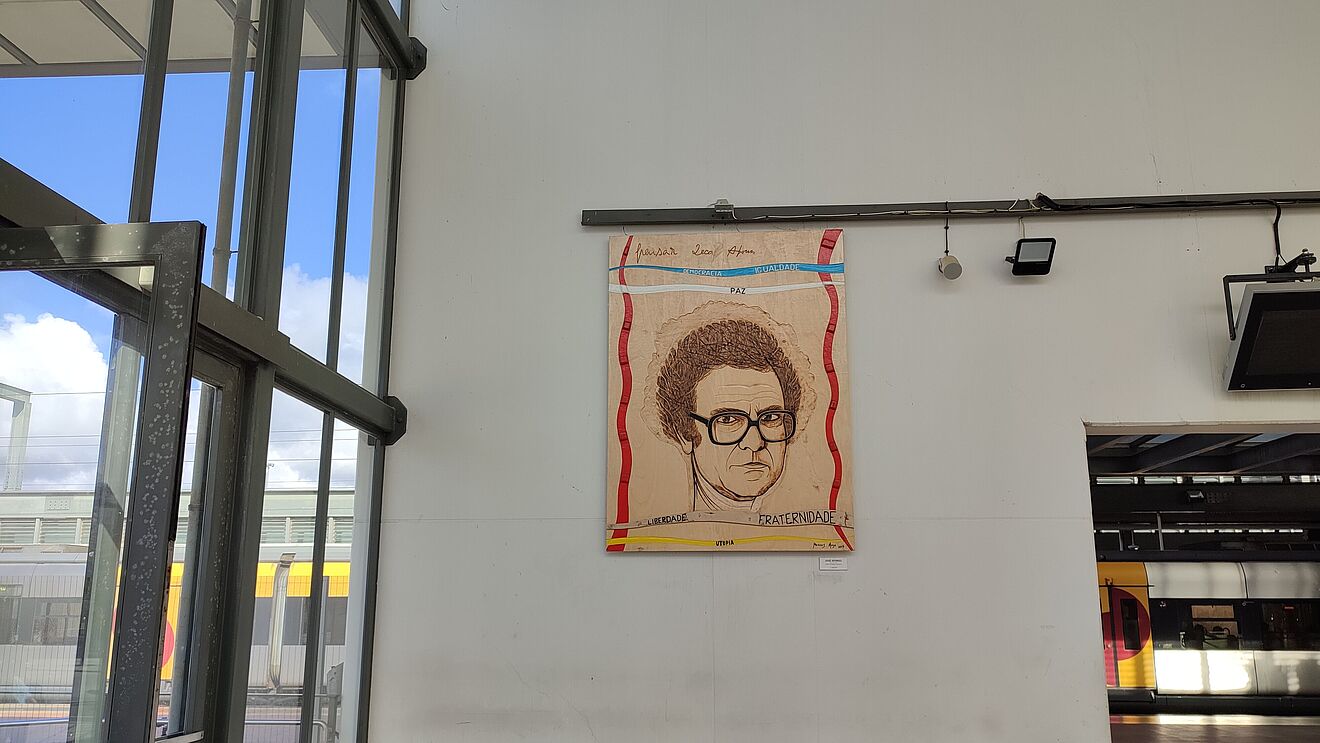

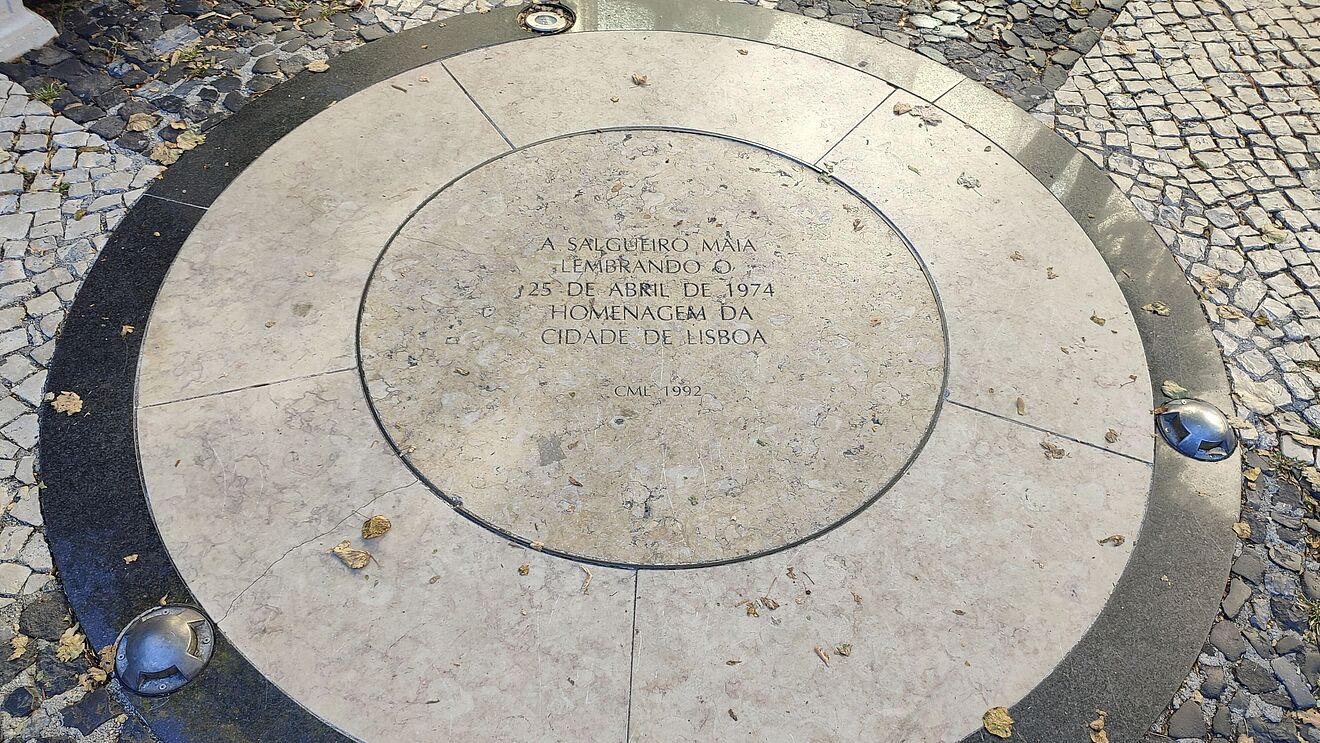

No historical event has had such a lasting impact on the topography of Portuguese cities in recent decades as the Carnation Revolution of 25th April 1974. The references to this event are multifaceted. On the one hand, there are the graffiti, already known since the revolution, with their typical socialist-revolutionary iconography that decorate concrete walls in Lisbon to this day. Popular motifs include the red carnation, the number 25, or Captain Salgueiro Maia, who stands pars pro toto for the Armed Forces Movement. On the other hand, there are numerous statues and monuments with comparable iconography commemorating 25th April, most of which were inaugurated on the anniversaries of the revolution. Finally, it is worth noting that 25th April has exerted a considerable impact on the toponymy of the major Portuguese cities. Not only street names demonstrate clear references to the events of April 1974, but also large structures. On example of this is the suspension bridge over the Tagus in Lisbon, which was renamed from its original moniker Salazar Bridge to the 25th of April Bridge.

In the course of the revolutionary upheaval in Portugal, the remnants of the former dictatorship were quickly removed from the country’s topography. This primarily concerned the statues and monuments of the dictator Salazar himself. The statue of Salazar which was created by Leopoldo de Almeida in Salazar’s home municipality of Santa Comba Dão in 1965 deserves special attention in this context. Immediately after the revolution, it was smeared and temporarily covered with black blankets, until it was finally decapitated in November 1975. Attempts to put the head back on led to massive riots that even claimed one life. In February 1978, the statue was blown up. Its remnants were replaced in 2010 by a monument dedicated to the “overseas fighters” in the Portuguese Colonial War. Thus, the statue was replaced by another highly contentious commemorative topic that is increasingly becoming the target of criticism.

Monuments and Topography in Spain

Even in democratic Spain after 1975, statues of dictator Francisco Franco and his military generals stood firmly on their pedestals. The turn of the millennium marked the beginning of the era of iconoclasm in Spain.

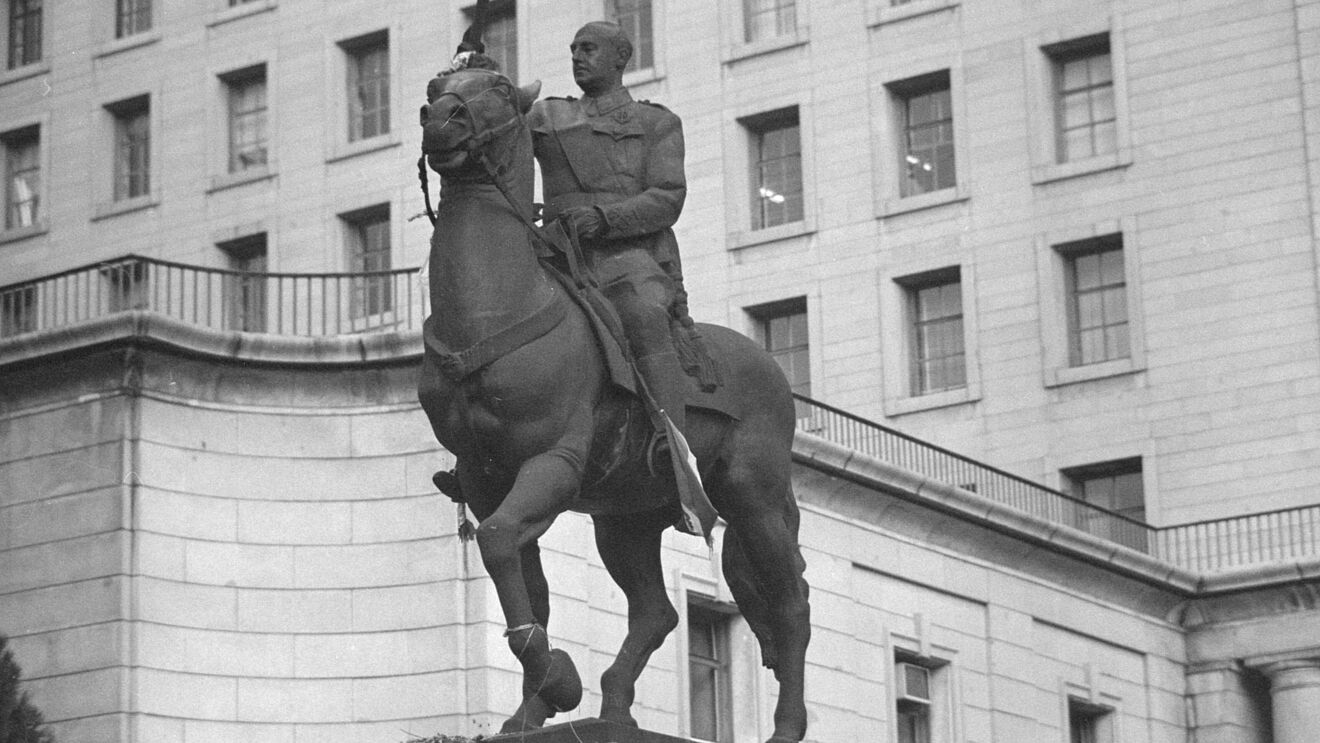

The political caesura dragged on for a full 11 hours. Although planned as a nightly cloak-and-dagger operation, it took a group of masked left-wing activists until the midday hours of September 10, 1983, to lift the equestrian statue of dictator Francisco Franco from its pedestal in Valencia's central town hall square with the help of a crane. Its removal – at the behest of the city government and accompanied by protests from ardent Franco supporters – marked a turning point. For a long time, the past of the Franco dictatorship continued to dominate the streetscape even in democratic Spain. Equestrian statues of the dictator, erected primarily in the 1960s, adorned central squares in Madrid, Valencia, Santander, Barcelona, and Zaragoza. At the same time, monuments dedicated to the nationalist generals and military officers who had planned the 1936 coup stood in their respective hometowns – and remained there long after Spain’s democratic transition.

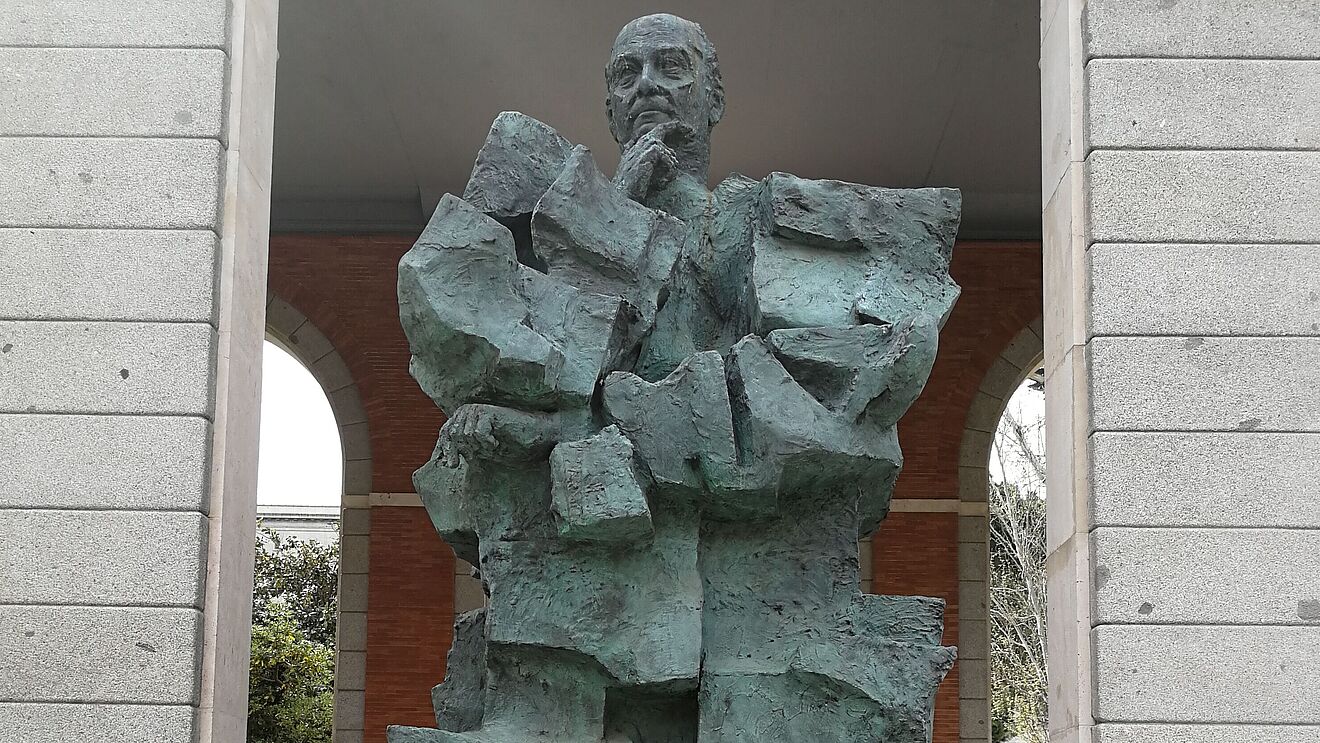

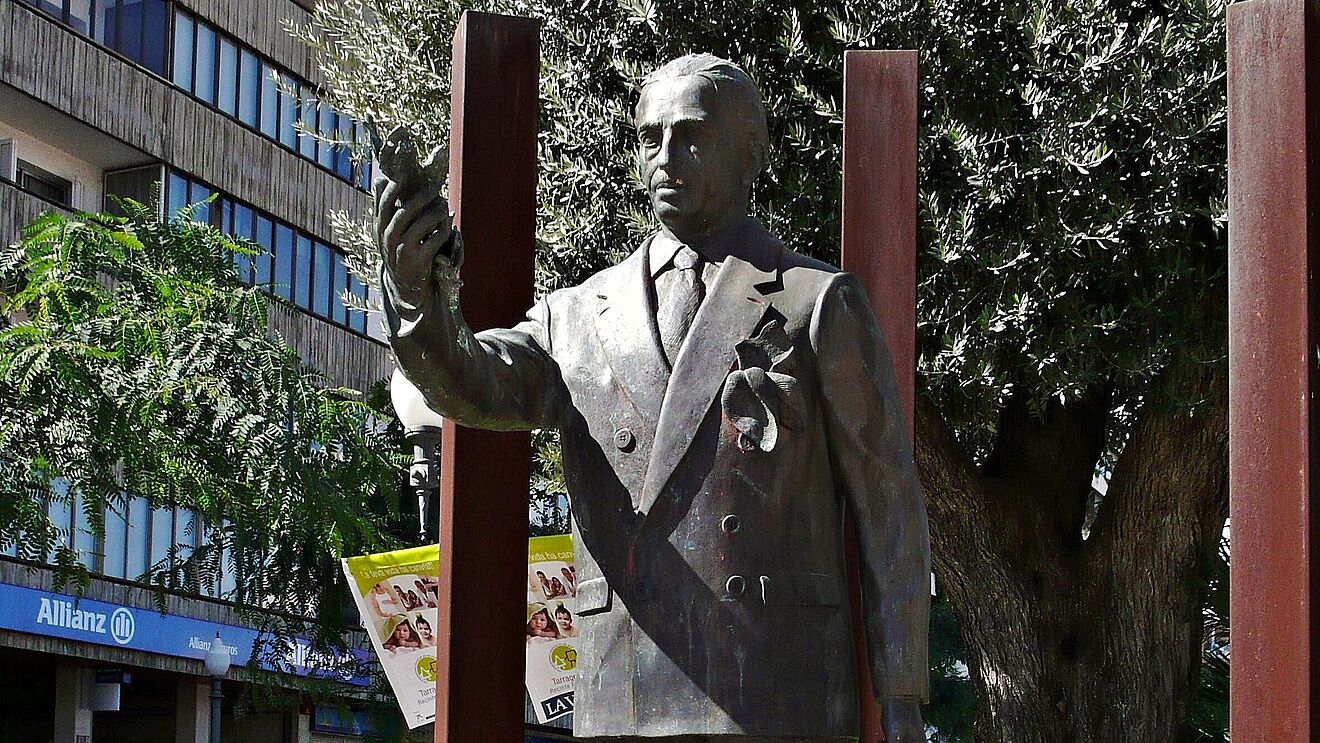

Contrary to these continuities, the Socialist PSOE government of Prime Minister Felipe González (1982–1996) was already working on the construction of distinctive counter-memorials in the form of statues in the mid-1980s. Thus, four monuments representing political leaders of the Second Republic were erected in the Madrid metropolitan area: the Social Democratic ministers Indalecio Prieto and Francisco Largo Caballero, Parliament Speaker Julián Besteiro, and President Manuel Azaña of the Republican Left. The renowned Spanish sculptors Pablo Serrano Aguilar and José Noja Ortega, who had spent long periods of Franco's dictatorship in American exile and who had returned to their homeland after the dictator's death, were responsible for the brutalist rubble look of the statues. In addition, the last president of the Catalan regional government, Lluis Companys, who had been executed by Franco's nationalists in 1940, was honored with a mausoleum in Barcelona in 1985.

A major wave of iconoclasm began at the turn of the millennium, primarily due to the 2007 Law of Historic Remembrance. Accordingly, Franco's equestrian statues in Madrid, Zaragoza, Barcelona, and Santander were dismantled between 2005 and 2008. Franco monuments persisted much longer in the Spanish periphery. A statue in the Spanish exclave of Melilla in Morocco, depicting Franco as a colonial officer of the Spanish-Moroccan War, was not removed until early 2021. To this day, the Franco statue of Santa Cruz, the capital of the island of Tenerife, remains in its place. Depicting the long-time dictator with embellished facial features, sword and cape, enthroned on an angel of victory, the statue was renamed "Monument to the Fallen Angel" by the conservative-dominated city council in 2010 to protect it from imminent dismantling.

Links

Video of the Dismantling of the Franco Equestrian Statue of Valencia, 1983 (Spanish)

Statues of Francisco Largo Caballero and Indalecio Prieto in Madrid (Google Streetview)

Statue of Manuel Azaña in Alcalá de Henares (Google Streetview)

„Monument for the Fallen Angel” in Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Google Streetview)

Hispanist Aleksandra Hadzelek on the Dismantling of Franco Statues (English)