Universal Jurisdiction and Transnational Judicial Processes between Spain, Argentina, and Chile

In 2002, the foundation of the International Criminal Court in The Hague created a permanent instance for the punishment of human rights crimes. The military dictatorships in Spain, Argentina and Chile were now scrutinized according to the changing paradigms of a globally intertwined post-Cold War world.

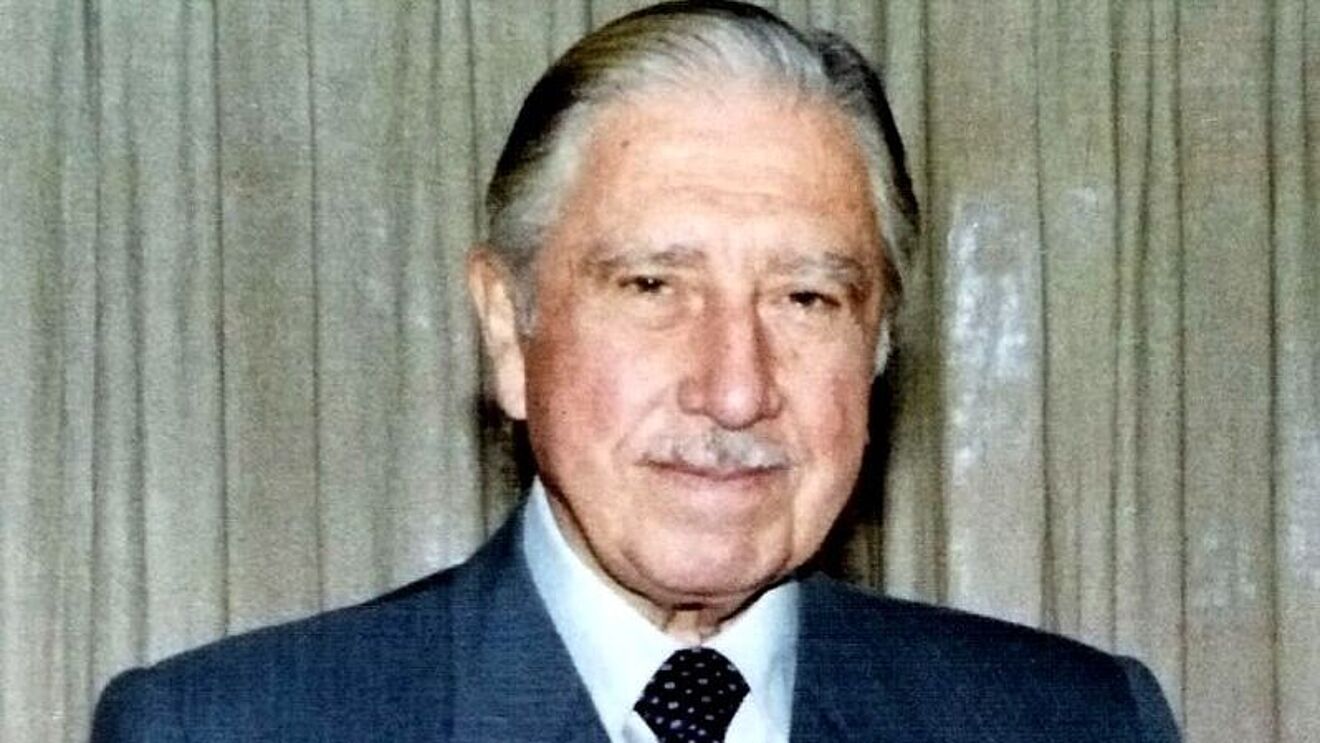

"Better late than never" and "Justice now!" Protest banners like this were held aloft by numerous demonstrators in October 1998 outside London Bridge Hospital, where Chilean ex-dictator Augusto Pinochet underwent treatment and now found himself placed under house arrest as the result of an international arrest warrant. News of Pinochet's indictment by Madrid’s investigating judge Baltasar Garzón for the murder of 194 Spanish citizens hit Britain, Chile, and even Spain like a bombshell. While Britain’s House of Lords, as the country’s highest judicial authority, argued for Pinochet's extradition to Spain, the legal process quickly became a political affair. Although former heads of government Margaret Thatcher and George H. W. Bush, who were well-disposed towards Pinochet, argued that he could only be tried in his own country, Mary Robinson, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, supported the British verdict. Even though Home Secretary Jack Straw allowed Pinochet to leave for Chile after two years of legal struggle, the trial represented a turning point, especially for Spain.

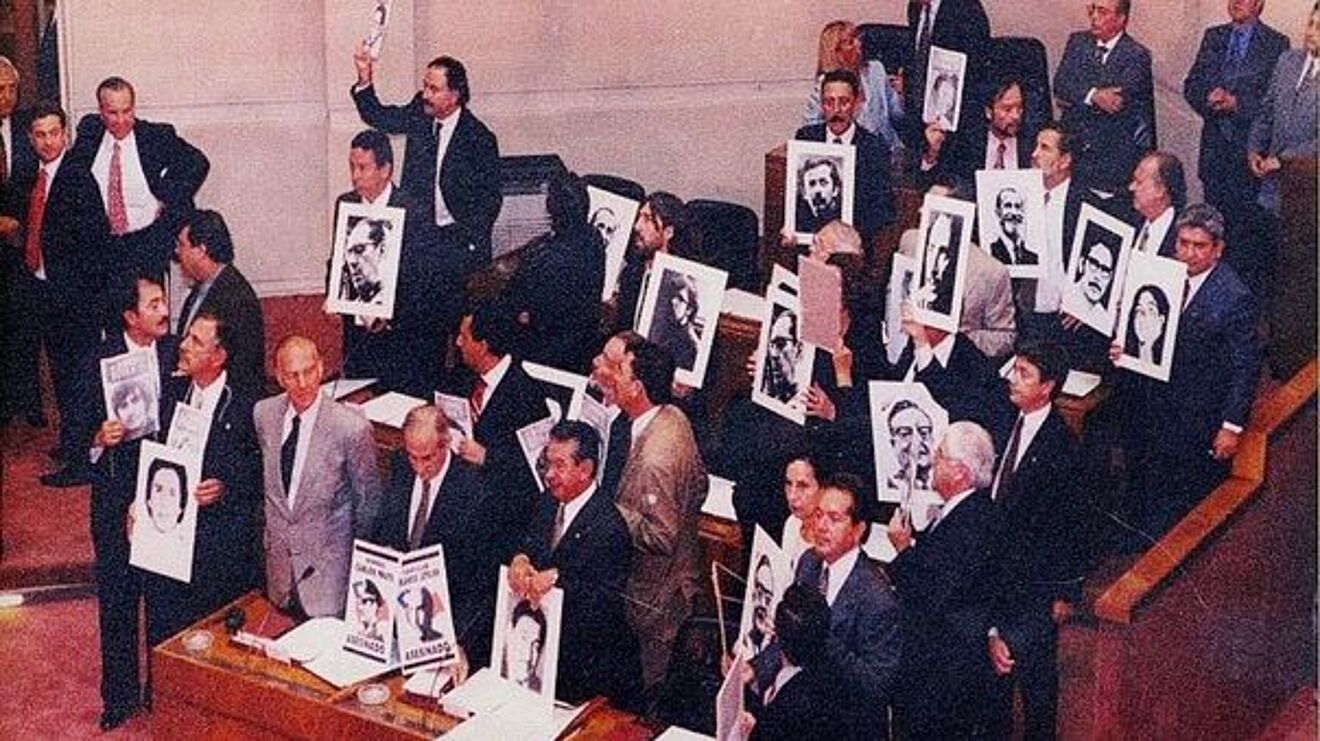

Since the Court of Appeals of the Audiencia Nacional upheld Garzón's viewpoint that national amnesty laws such as the Chilean decree of 1978 did not override Spanish law, Madrid soon emerged as the central hub of universal jurisdiction. Judge Garzón would become its most distinguished advocate, dragging Adolfo Scilingo, a torturer active during the Argentine military dictatorship who had since relocated to Spain, before Spain's Supreme Court in 2005. Scilingo was involved in the so-called "death flights" – a practice in which drugged prisoners were dropped from planes and helicopters over the bay of the Río de la Plata to drown in the Atlantic Ocean. He was sentenced to 640 years in prison, in part because Argentina showed a willingness to cooperate. The sentence was increased to 1084 years in prison in 2007 after more cases came to light. Spain’s legal paradox now consisted of the contradiction that, while Madrid’s courts were prosecuting human rights criminals around the world, Spain’s own problematic past remained untouched because of the 1977 amnesty law. In 2008, Garzón’s attempt to clarify the whereabouts of 130,000 disappeared persons from the Civil War was thus denied by the Audiencia Nacional.

In 2013, Argentine judge María Romilda Servini acted in the opposite direction. In 2010, two Spaniards living in Argentina had filed lawsuits against the Franco regime's human rights crimes. They were joined by 5,000 other plaintiffs in two years. Servini issued international search and arrest warrants against four members of the Spanish security forces, but these were rejected by the Audiencia Nacional in 2014, which cited Spain's 1977 amnesty law in its decision. Servini then brought charges against 20 high-ranking politicians, who belonged to the last Franco and first UCD governments of Adolfo Suárez. Ex-Interior Minister Rodolfo Martín Villa and ex-Minister of Construction José Utrera Molina were among their number. Despite the verdict of UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion of Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence, Pablo de Greiff, that Spain had an obligation to prosecute the accused, the Spanish cabinet refused to extradite them in 2015. To date, the primacy of international jurisdiction in Spain thereby remains unfulfilled.

Political Exile and Memory Transfer in Brazil

A transnational interweaving between the historically connected nations of Portugal and Brazil became evident once again in recent history. During the Carnation Revolution, both countries were popular destinations for (political) exile. Especially in relation to the commemorations of 25th April, a cultural permeability between the countries can be observed.

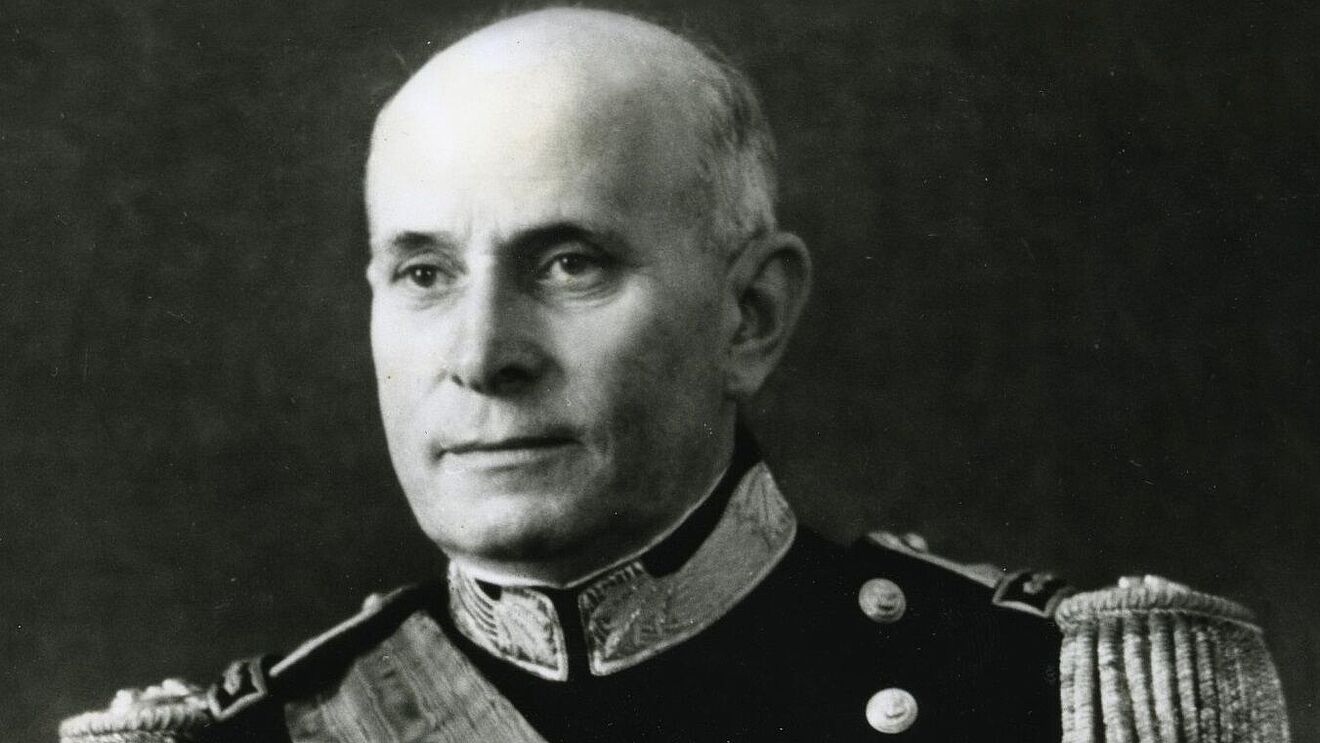

“When Spínola wanted to invade Portugal with the help of Brazil”. This was Manuel Carvalho’s headline in Público on 27th April 2014. António de Spínola – the Portuguese Charles de Gaulle with a monocle – commanded the Portuguese troops in the Colonial War in Guinea-Bissau in the service of the Estado Novo between 1968 and 1973. In the final phase of the dictatorship, he attracted attention with his book Portugal e o Futuro (1974), which expressed strong criticism against the dictatorial regime. His disobedience drew the interest of the military opposition. On 25th April 1974, he was elected by the MFA as the first president of the transition. The conservative Spínola quickly became disgruntled with the course of the revolution, had to resign on 30th September 1974 and finally fled into exile in Brazil via Spain and Argentina after an unsuccessful coup attempt on 11th March 1975. The Brazilian military dictatorship’s approval of Spínola’s request for asylum put a strain on Luso-Brazilian relations. This was not least due to the fact that, once in Brazil, the restless general founded the “Democratic Movement for the Liberation of Portugal” (MDLP). This organisation agitated against the developments in Spinola’s mother country and became a disruptive factor in the democratic consolidation in Portugal that has received little attention in research to this day. This is, perhaps, all the more surprising given that Günter Wallraff’s publication of Spínola's renewed coup plans at the beginning of April 1976 attracted international attention.

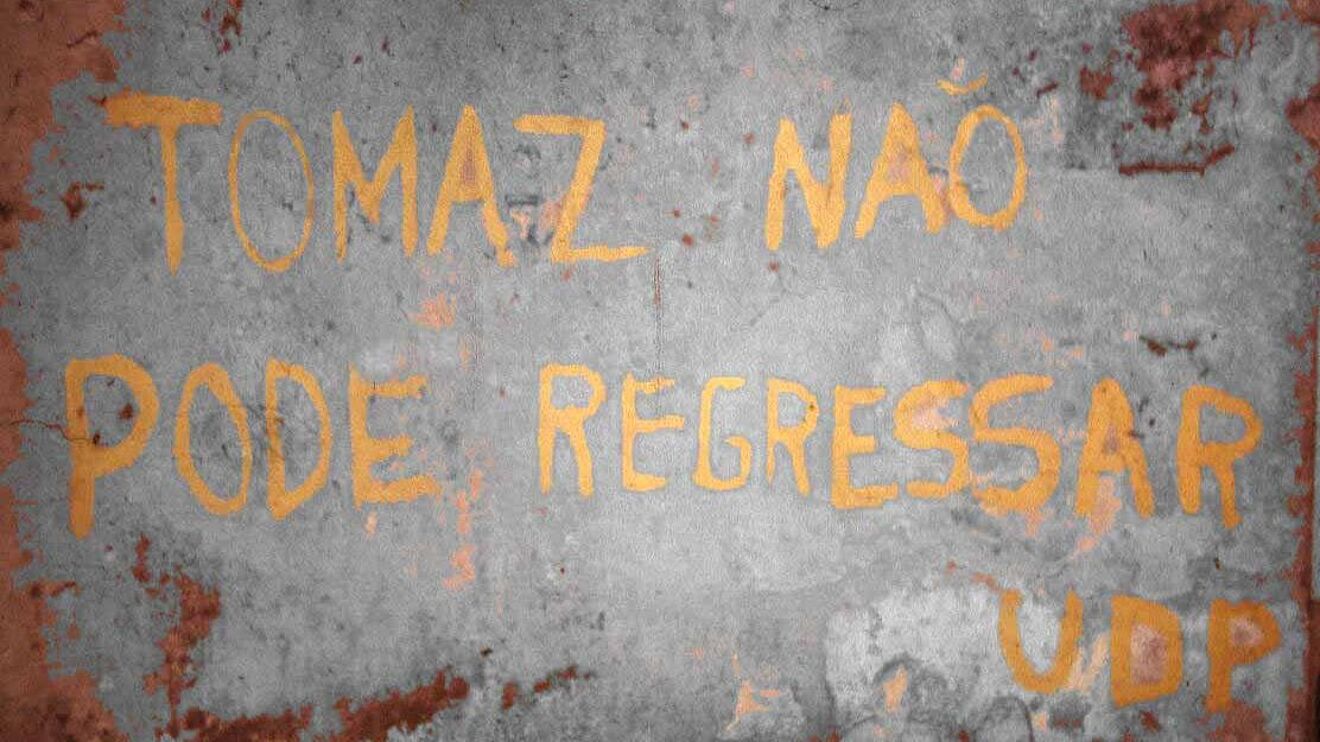

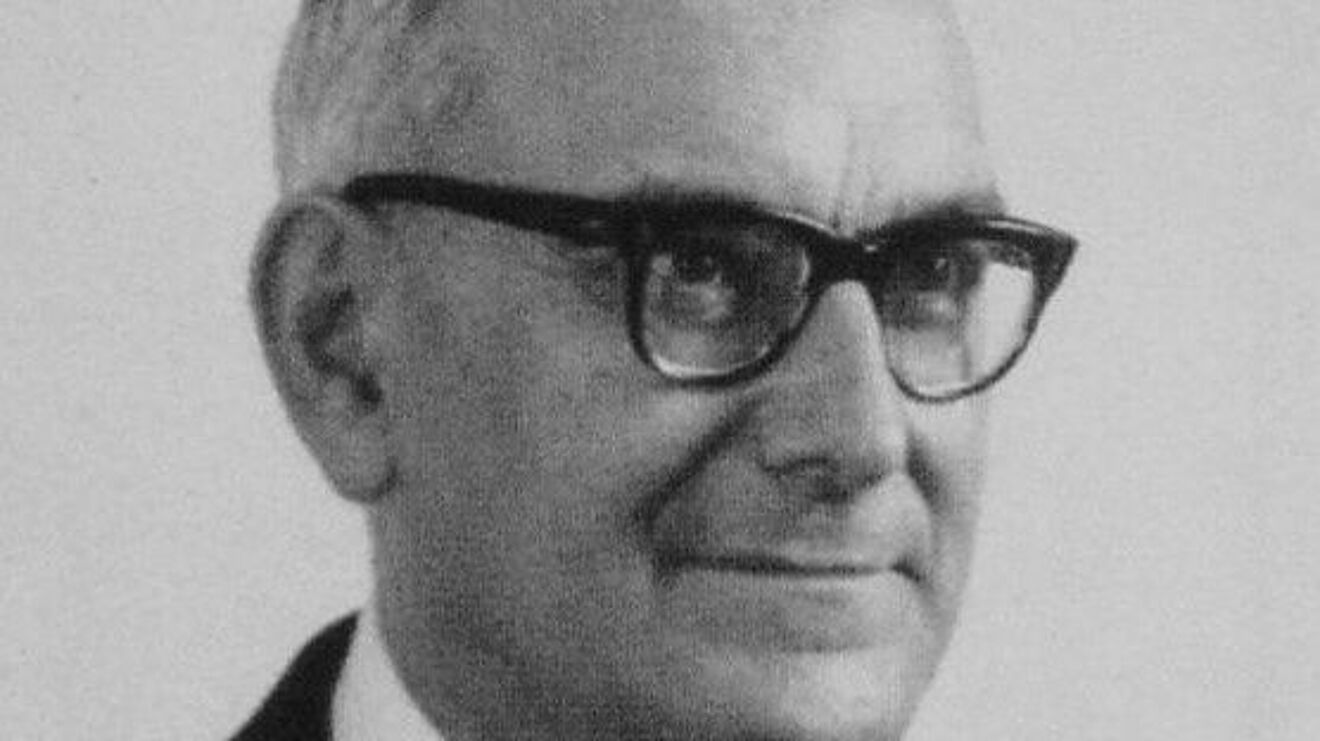

Even before Spínola was granted asylum, the Brazilian military dictatorship was already hosting two prominent exiles from the overthrown Portuguese dictatorship – the former prime minister, Marcello Caetano, and the former president, Américo Tomás. Caetano, in particular, quickly gained a foothold in Brazil. On 1st June 1974, he was appointed Professor of Comparative Law in Rio de Janeiro at the Gama de Filho University. In addition to his active professional life in exile, Caetano was keen to leave his mark on the memory of himself, Salazar and the Estado Novo. Most notably, his “Statement” (Depoimento) on the Carnation Revolution caused considerable tension in Luso-Brazilian relations in 1974, as Brasília did not comply with Portuguese demands to inhibit the publication of the book. The impact of other revisionist works by Caetano – A Verdade Sobre 25 de Abril (1976), Minhas Memórias de Salazar (1977) – as well as Thomáz’ Últimas Decadas de Portugal (1980) – on Portuguese memory culture also deserves scholarly attention.

That the 25th April is a widespread phenomenon in Portugal has already been discussed elsewhere. In fact, the celebrations transcend the national borders of Portugal and are also celebrated on a smaller scale in other European countries and especially in Brazil. The transnationalisation of this Portuguese commemorative practice can be demonstrated by the “Cultural Centre 25 April” in São Paulo. It was founded in 1982 by the Portuguese-born Ildefenso Octávio Severino Garcia, who emigrated to Brazil at the age of eighteen. In parallel with the celebrations in Portugal, the cultural centre holds meetings on 25th April to commemorate the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. Furthermore, the monument “The Gate of April” – an homage to 25th April – can be visited in São Paulo. It was created in 2001 by the Portuguese sculptor José Manuel Aurélio and donated to the Brazilian city.