The Technocratic Military Dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985)

The military ruled Brazil for a full 21 years (1964–1985). In the context of the Cold War, they proceeded with extreme brutality, especially against the communist opposition. In the climate of “order”, a technocratic elite was then supposed to ensure the country’s economic development.

On 31st March 1964, a large right-wing coalition drawn from conservative church circles, the business elite, leading military officers, some governors and the US ambassador joined forces in Brazil to stop the incipient socialist “land reforms” of the then president João Goulart and remove him from office. The military did not relinquish power in the aftermath of these events, but rather consolidated their position within the existing constitutional order through so-called Institutional Acts, whereby they could amend or suspend the constitution as they saw fit. By October 1969, the first Institutional Act had been followed by 16 others. For the next 21 years, a succession of five four-star generals held the position of head of state. These individuals can be divided into two main ideological currents: on the one hand, the “moderate line” – also called the Grupo Sorbonne or Castelistas – under Humberto Castelo Branco (1964–1967), Ernesto Geisel (1974–1979) and João Baptisto de Oliveira Figueiredo (1979–1985). On the other hand, the “hard line” under Artur da Costa e Silva (1967–1969) and Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969–1974).

The establishment of the military dictatorship was followed by the elimination of the political opposition. Thousands of politicians and civil servants lost their political rights in “Operation Purge”. In the name of the regime’s first ideological pillar, the “National Security Doctrine”, the repressive apparatus was rapidly built up, spearheaded by the SNI intelligence and security service. Both the first ideological pillar of the regime and the second pillar of “Economic Development” were pushed even harder from October 1967 under the hard-liner Artur da Costa e Silva. With the help of technocrats in economic policy, the regime achieved the “Brazilian Economic Miracle” between 1968 and 1973. Under the cover of the economic upturn, the hard-liners, especially during the presidency of Emílio Garrastazu Médici, were able to increase repression considerably. Political opponents were persecuted, tortured and in over 400 cases murdered. The presidency of Ernesto Geisel, who pursued a controlled opening of the regime, brought about a political change from 1974 onwards.

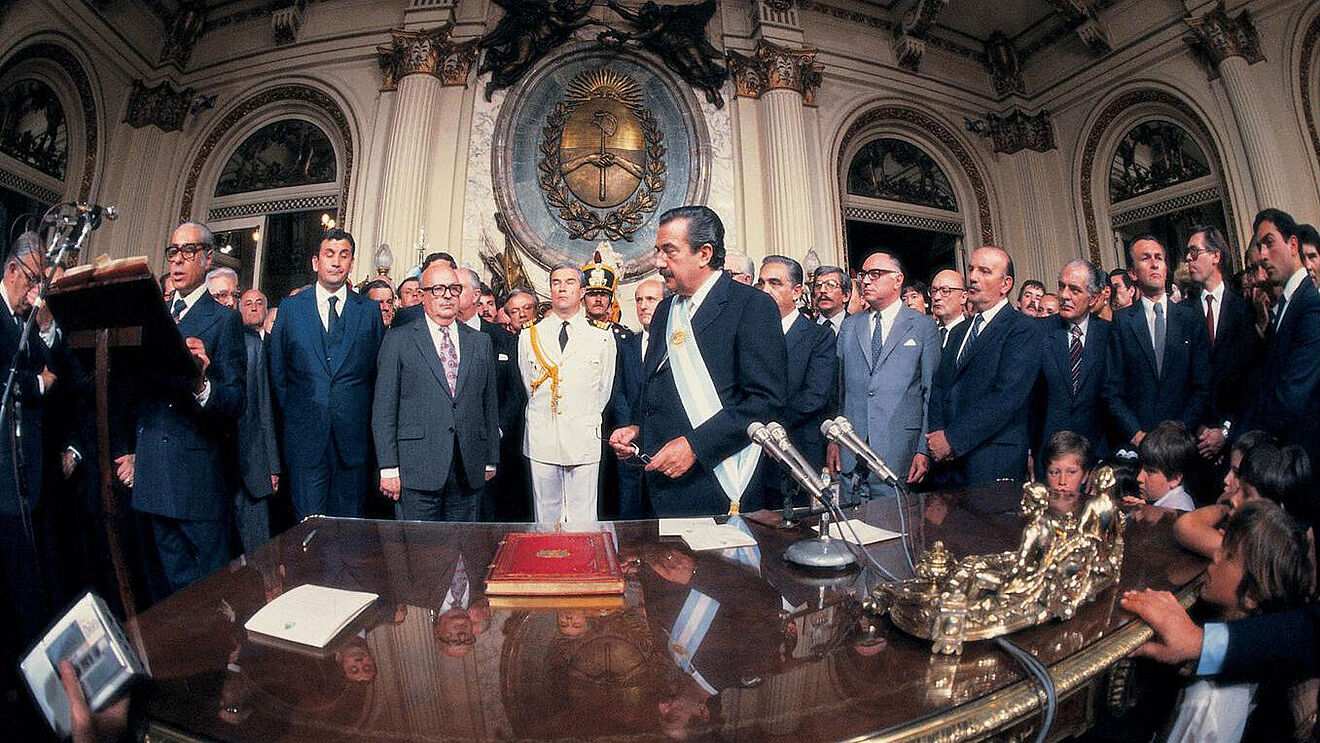

On 15th March 1979, João Baptista de Oliveira Figueiredo, the former head of the SNI and the preferred candidate of the moderate line, took over as president. He was to hand over power to a civilian president. One of the first steps towards democratisation was the return from a two-party system to a multi-party one. The Amnesty Law of 28th August 1979, originally intended as a concession to the left-wing opposition, not only granted amnesty for opposition crimes, but also decreed that all crimes committed under the military dictatorship would remain unpunished. The regime eventually lost popular support due to the failure of its economic policy and the continued absence of civil liberties. The growing discontent came to a head in 1984 in mass demonstrations (“Direct Elections Now!”). Even though the military did not allow direct presidential elections, the opposition candidate Tancredo Neves prevailed in Congress as the presidential candidate. However, he died before he could take office. José Sarney, a vice president loyal to the regime, became interim president in 1985. With the adoption of the 1988 constitution, the transition to the “New Republic” in Brazil was considered complete.

The Dictatorship of Pinochet in Chile (1973–1990) and the Military Junta in Argentina (1976–1983)

During the Spanish Transición, military juntas took power by means of coups in Chile and Argentina. After grave human rights violations and mass crimes, the military presidents ceded power in the 1980s – and amnestied themselves, following the Spanish model.

"In view of the terrible social and moral crisis that beleaguers the country [and] the government's inability to control the chaos [...], the armed and police forces stand united to begin their historic and responsible mission to liberate the fatherland." With these words, the military junta led by Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army Augusto Pinochet legitimized its coup against Chile's socialist President Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973. Three years earlier, Allende had been elected to office by a narrow majority. Fighting poverty with nationalizations and a generous social policy, he would at the same time plunge the country into a severe economic crisis via galloping inflation and estrange Chile from the United States. Washington thus immediately recognized Pinochet as legitimate president in 1973. Three years later, the military also seized power in Argentina. Here, it was the vacuum left by the death of President Juan Domingo Perón, a growing economic crisis, and increased assassinations by the leftist urban guerrillas Montoneros that prompted the military around General Jorge Videla to place Perón's wife, vice president and successor, Isabel Martínez de Perón, under house arrest.

Especially in the months immediately following the respective takeovers, the junta governments in Chile and Argentina committed grave human rights violations and mass crimes. Pinochet – an ardent admirer of Franco, who was one of the few state guests to attend the Spanish dictator's funeral in 1975 – primarily used the DINA secret police to kidnap, torture and execute disfavored opposition figures. In Argentina, President Videla declared as subversives all those who would undermine the country's Christian values with "ideas contrary to our civilization." Here, too, dissenters were kidnapped, tortured, and killed. In Chile, about 3,000 of 30,000 torture victims died. In Argentina, between 6,000 and 30,000 people disappeared. Determining an exact figure is made more difficult by the practice of "disappearing," which involved abductions without certainty regarding the whereabouts of those detained. While Pinochet based his legitimacy on a temporary improvement in Chile's economic situation through monetary structural reforms as well as on manipulated referendums, the Argentine military junta's situation remained precarious throughout due to the country’s unstable economic situation. Major publicity stunts such as the hosting of the 1978 World Cup could hardly distract from this fact.

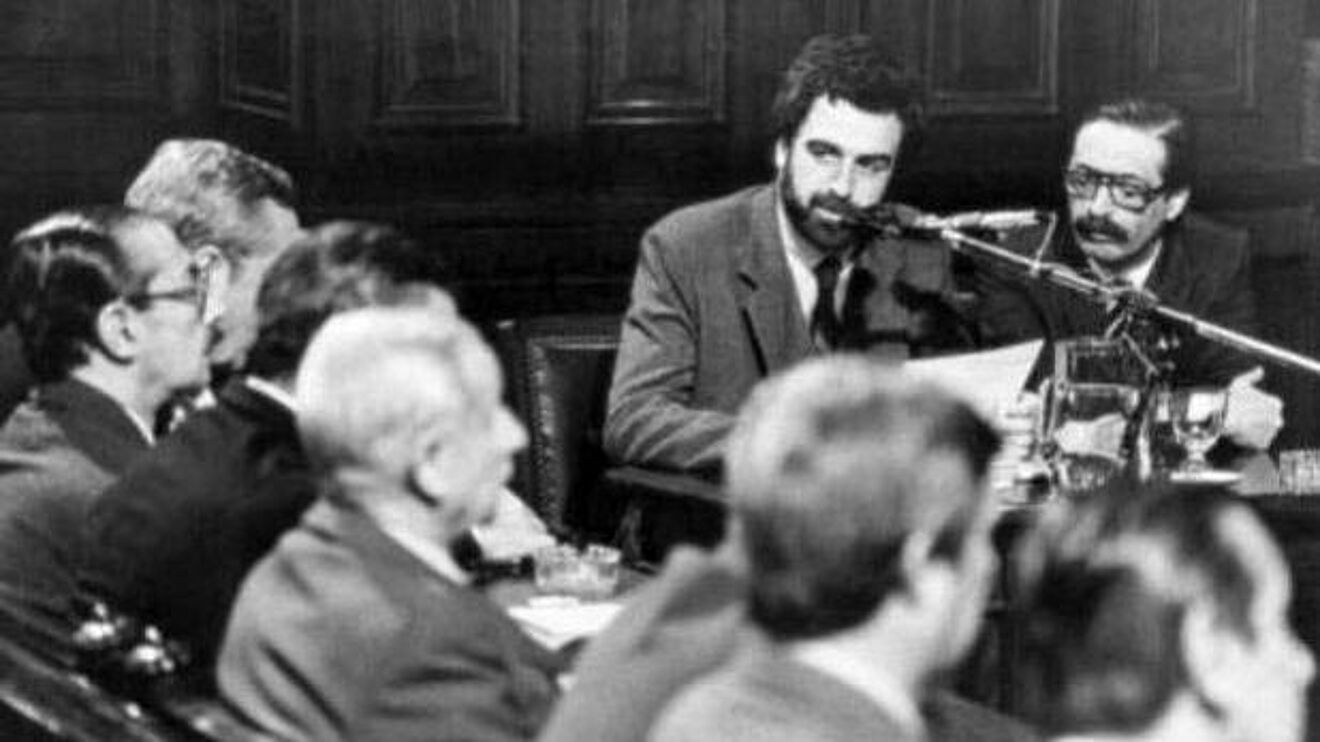

With the occupation of the Falkland Islands off the Argentine coast – a British colony since 1833 – the new Argentine president, General Leopoldo Galtieri, aimed at unleashing a wave of national euphoria in 1982. However, the successful British counter-operation dealt a death blow to the military junta. In 1983, Reynaldo Bignone, Argentina's last military president, called free elections. An amnesty law guaranteed the former rulers immunity from prosecution. In Chile, President Pinochet wanted to boost his legitimacy in 1988 by holding another referendum, which he surprisingly lost. Despite the free elections of 1989, Pinochet, who secured himself the offices of army chief and senator for life, remained an influential figure in Chilean politics. Although two truth commissions in 1991 and 2004 investigated the crimes of the Pinochet years, there were no legal consequences for the former ruler, who died in 2006, since a 1978 amnesty law protected him from prosecution. The situation was different in Argentina, where the CONADEP truth commission presented a dossier of human rights violations in 1984. Based on this report, the military junta’s decision-makers – including Videla, Galtieri and Bignone – were sentenced to lengthy prison terms in 1985.