Kooperation der SPD mit den portugiesischen Sozialisten

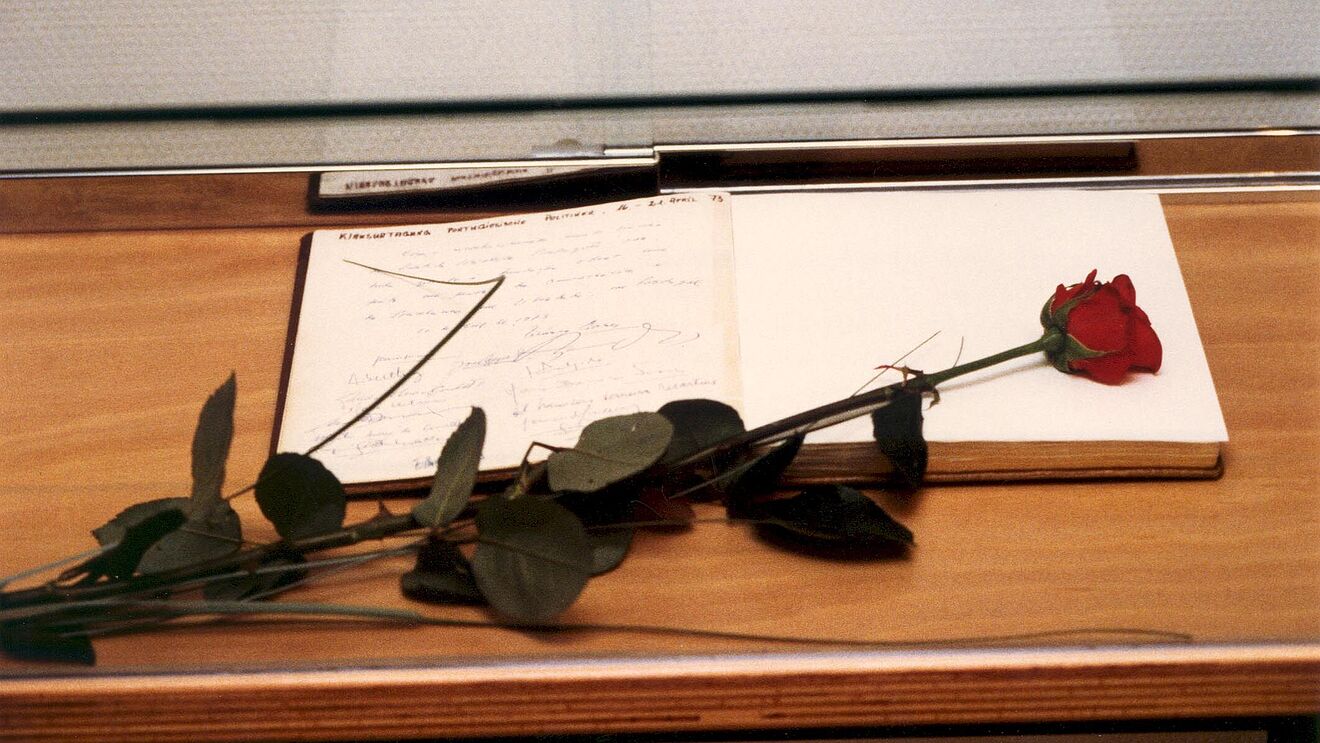

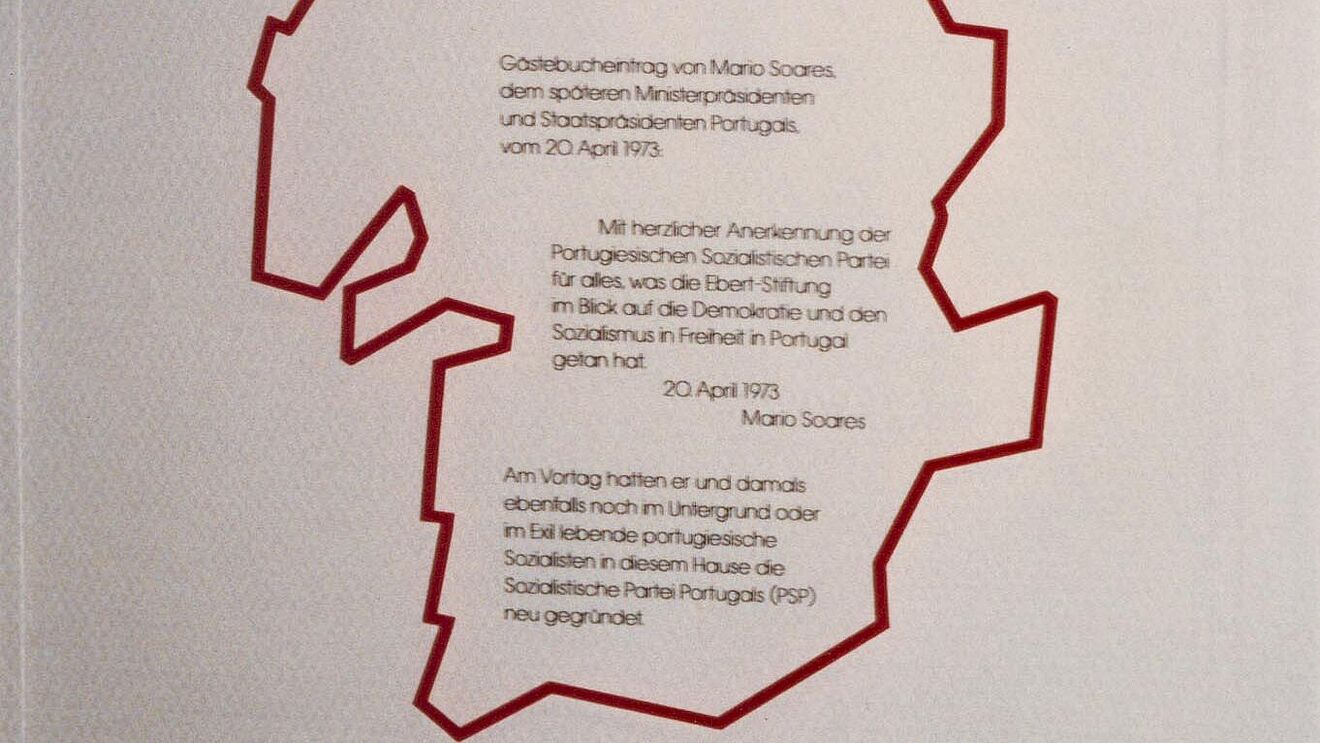

Als Mário Soares im September 1966 das erste Mal Kontakt mit der SPD aufnahm, konnte niemand damit rechnen, dass der wichtigste internationale Partner für die Demokratisierung Portugals gefunden war. Denn zunächst schien die Verbindung zwischen deutscher Sozialdemokratie und der sozialistischen Opposition im Estado Novo nicht gerade vielversprechend. Willy Brandt – seit 1966 als Vizekanzler und Außenminister selbst in Regierungsverantwortung – hielt es trotz des Wissens um eine aufkeimende sozialistische Opposition in Portugal nicht für gangbar, eine Kursänderung in den bilateralen Beziehungen zum „Neuen Staat“ einzuleiten. Vielmehr setzte man in der SPD auf eine Backchannel-Diplomatie: Während der offizielle außenpolitische Kurs bis zum Sturz des Estado Novo weitergeführt wurde, sollte die parteinahe FES den Kontakt zur Gruppe um Soares aufnehmen, um die portugiesischen Genossen der Sozialistischen Aktion (ASP) zu unterstützen - so zum Beispiel 1970 bei der Neugründung der Zeitung República. Der augenfällige Höhepunkt dieses Vorgehens war die Gründung der Sozialistischen Partei (PS) am 19. April 1973 bei einer Klausurtagung in Bad Münstereifel in der Nähe von Bonn.

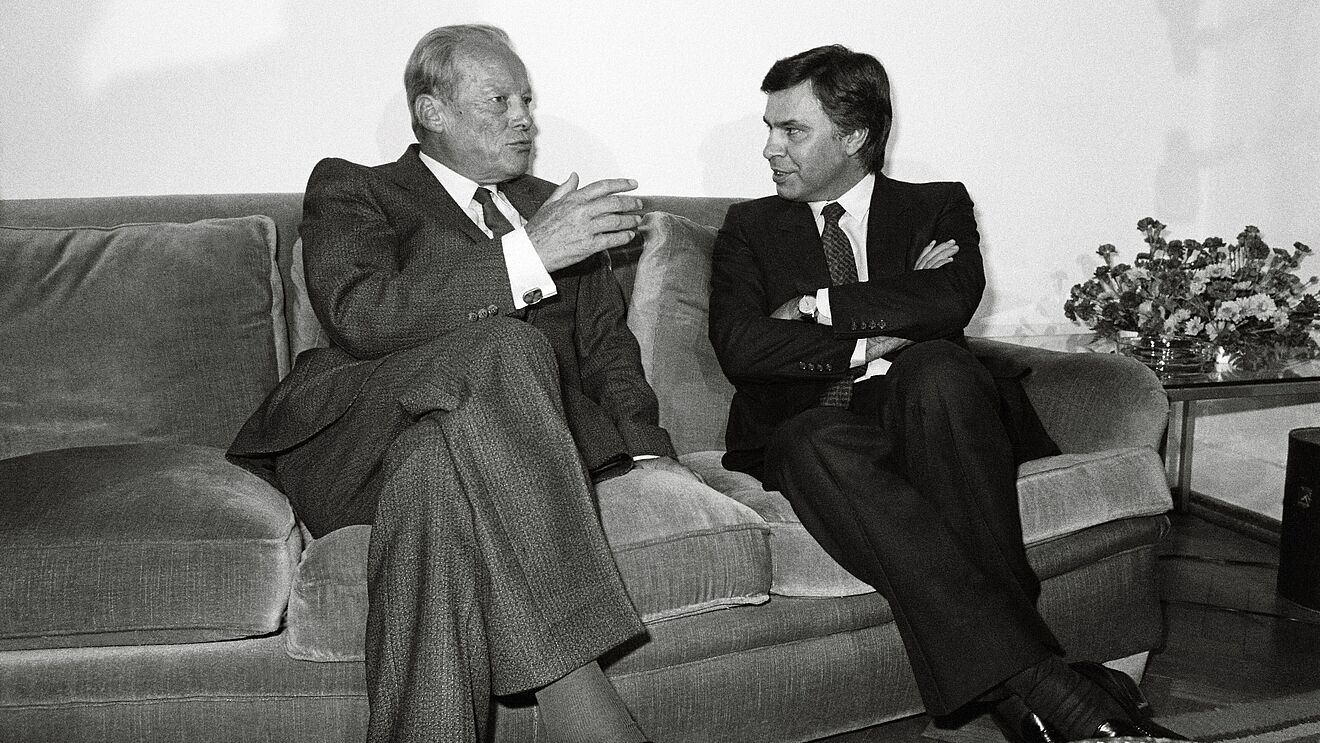

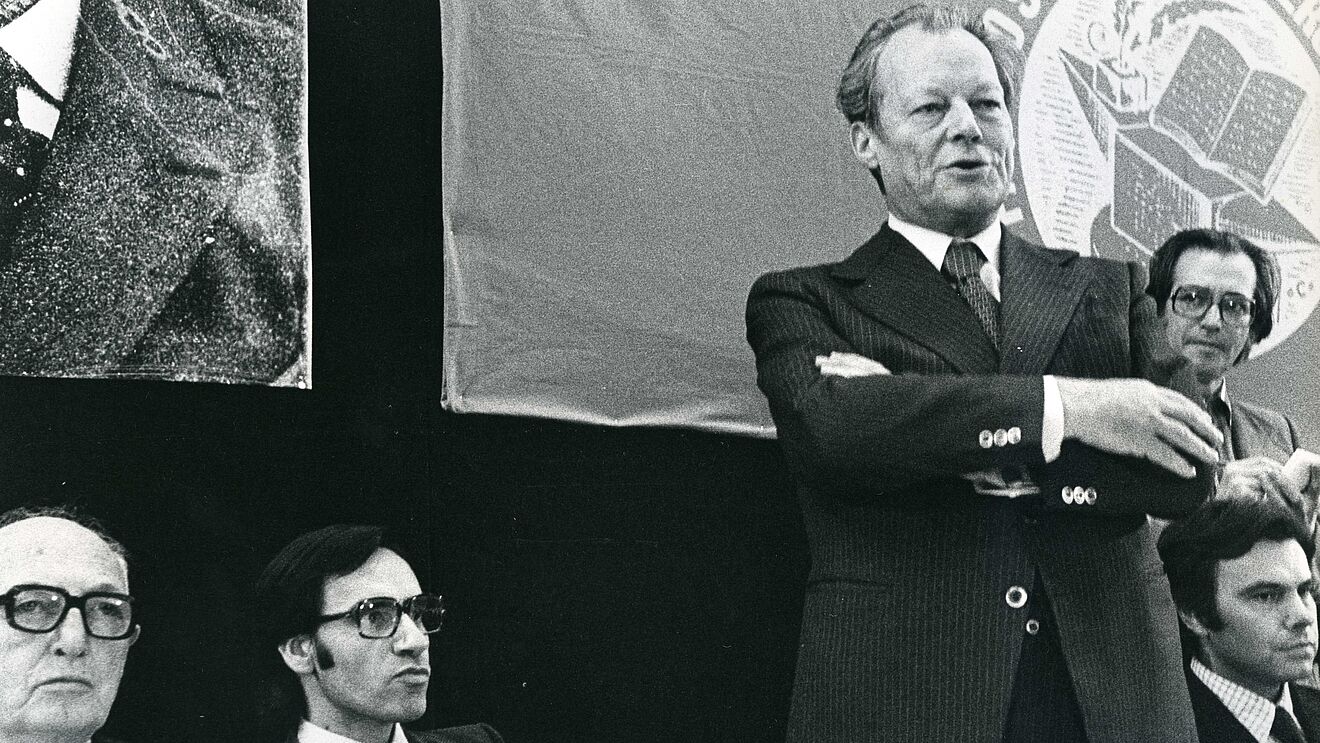

Die Nelkenrevolution leitete die intensivste Phase der Kooperationen zwischen SPD und PS ein. Die Partnerschaft lässt sich in zwei Hauptlinien aufteilen: Zum einen mussten die evidenten strukturellen Schwächen der PS in Portugal behoben werden. Hierfür leistete die FES finanzielle Direkthilfe beim Aufbau der politischen Infrastruktur und der Einrichtung von Parteibüros. Ebenso transferierte die FES wichtiges Know-how für die politische Kaderschmiede der PS und trug somit zur Schärfung des parteipolitischen Profils bei, das insbesondere in Abgrenzung zur Kommunistischen Partei (PCP) formuliert werden sollte. Zum anderen demonstrierte die SPD-Parteispitze ihre Solidarität mit den portugiesischen Genossen. Allen voran warf Willy Brandt durch offizielle Besuche in Portugal und den Vorsitz des „Komitees für Freundschaft und Solidarität mit Demokratie und Sozialismus in Portugal“ sein symbolisches Kapital als einer der führenden Vertreter der europäischen Sozialdemokratie in die Waagschale.

Die Aprilwahlen von 1975 und 1976 ließen die PS beide Male mit über 30% als stärkste Partei in Portugal hervorgehen. Angesichts des Wahlerfolges und der allmählichen demokratischen Konsolidierung in Portugal führten SPD und FES ihre Bemühungen fort. Ziel war es zunächst, der PCP das Monopol über die Gewerkschaften abzuringen. Für diesen Zweck wurde 1977 mit der José-Fontana-Stiftung ein Think-Tank gegründet, der über die FES reichlich vom BMZ bezuschusst wurde. 1979 errang die PS in einem Schulterschluss mit der Sozialdemokratischen Partei (PSD) schließlich auch die Hegemonie über die Gewerkschaften. Eine Anschubfinanzierung von zwei Million DM lieferte das BMZ – selbstverständlich durch Vermittlung der FES - auch für das wichtigste kommunalpolitische Projekt der PS, das Zentrum für Kommunalstudien und Regionale Aktion (CEMAR). In einem zentralistisch regierten Land wie Portugal mussten vor allem in der abgehängten ländlichen Peripherie politische Infrastrukturen aufgebaut werden.

Cooperaciones entre socialdemócratas alemanes y socialistas españoles

El SPD de Alemania (SPD) desempeñó un papel decisivo ayudando a los socialistas españoles del PSOE, debilitados por 40 años de dictadura franquista, a convertirse dentro de pocos años en un partido de gobierno fiable.

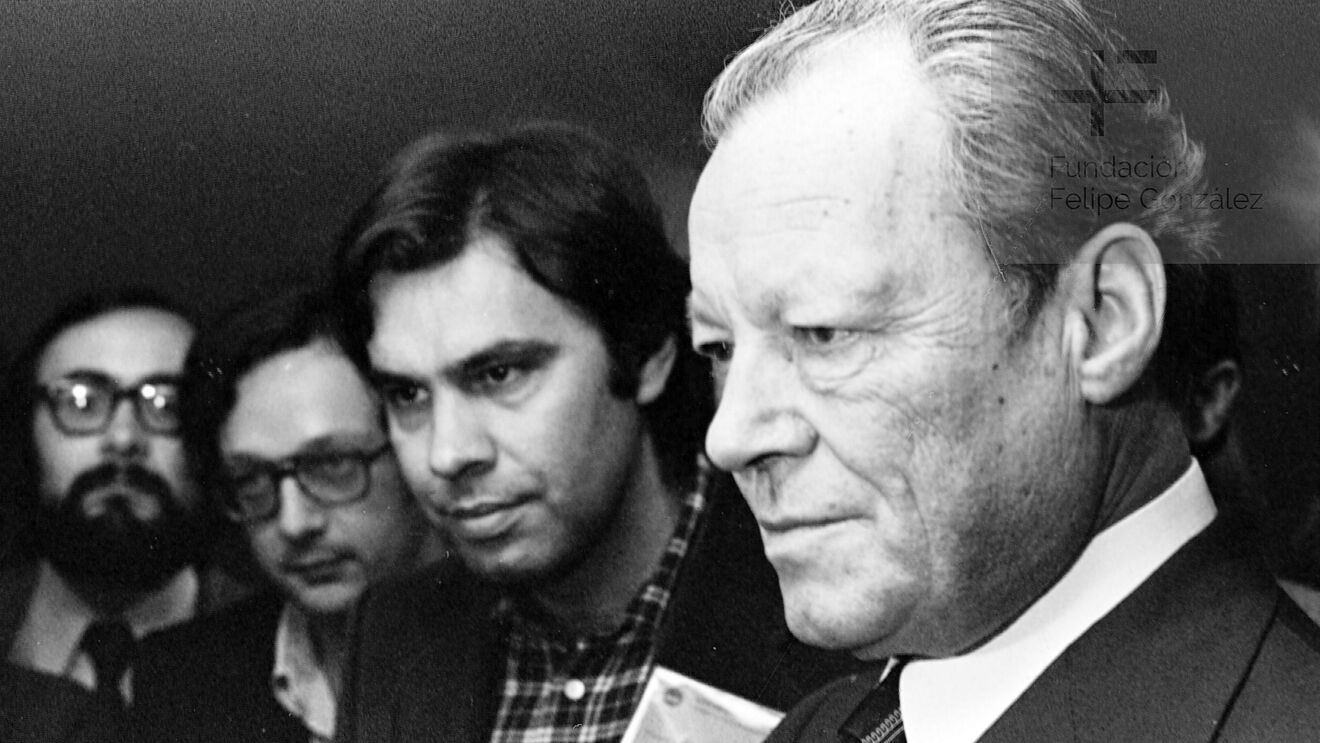

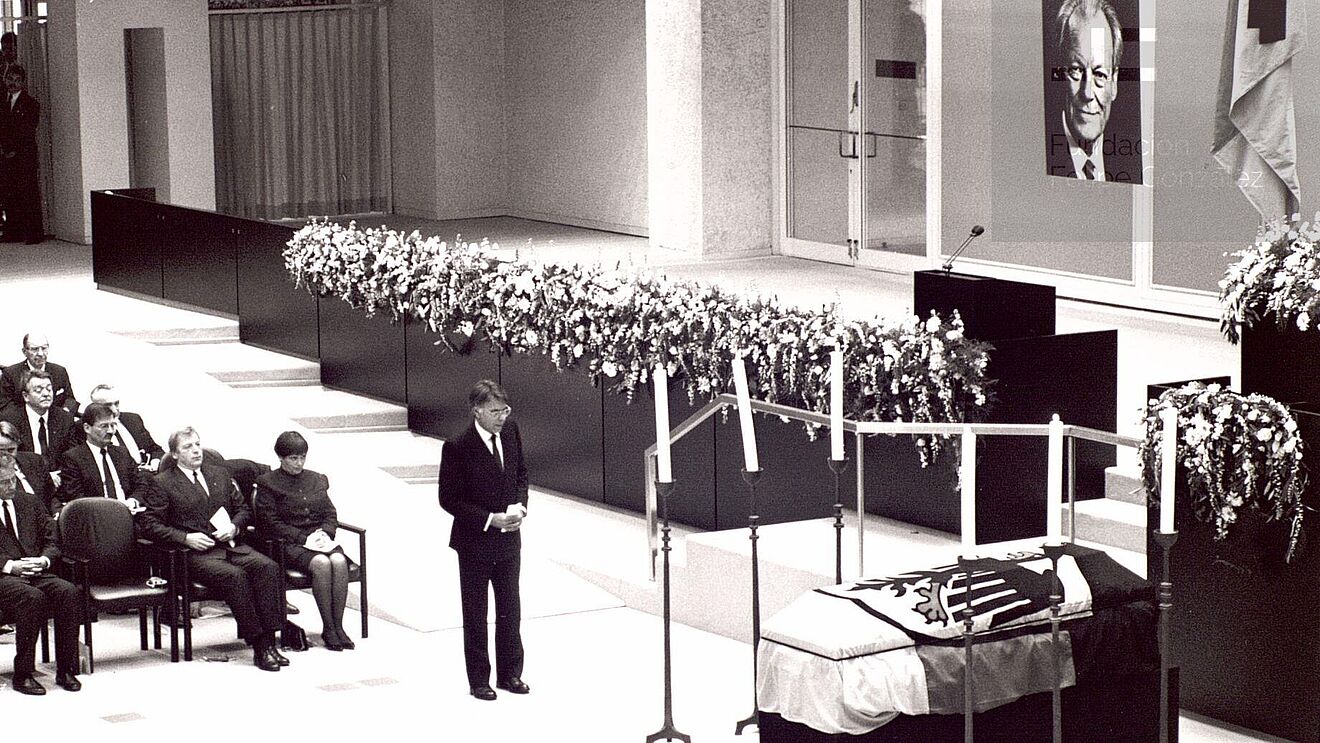

Con un "Adiós, amigo Willy" se despidió el presidente del gobierno español, Felipe González, del ex canciller alemán, que también había desempeñado el papel de presidente de la Internacional Socialista (IS) desde 1976 hasta su muerte, en el acto funerario por el fallecimiento de Willy Brandt en 1992. En efecto, los socialistas españoles debían mucho a sus amigos del SPD alemán. La derrota en la guerra civil había expulsado la izquierda al exilio. El partido obrero más antiguo de España, el Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), fundado en 1879, fue entonces dirigido desde Toulouse por el Secretario General Rodolfo Llopis tras la conclusión de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Tras la fundación de la República Federal de Alemania, el SPD adoptó inicialmente una postura radicalmente antifranquista y apoyaba al PSOE en el exilio. La política de los socialdemócratas alemanes hacia España cambió en el transcurso de los años sesenta. Tras un viaje a España de Fritz Erler en abril de 1965, el SPD se acercó a la resistencia interna española, encarnada sobre todo por el profesor universitario suspendido Enrique Tierno Galván y su Partido Socialista del Interior (PSI), fundado en 1968.

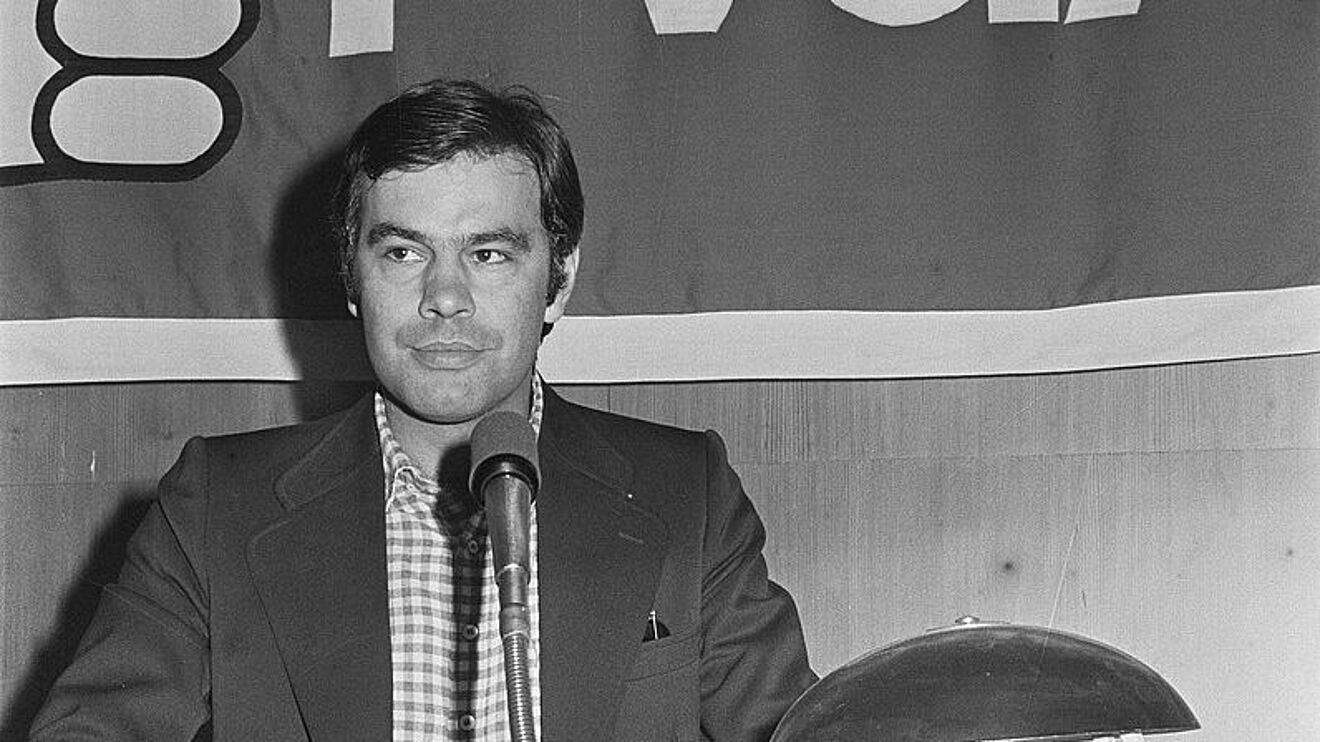

Sin embargo, tras un cambio generacional en el congreso del PSOE celebrado en 1974 en Suresnes (Francia), que eligió como nuevo secretario general al joven abogado Felipe González, de mentalidad reformista, el SPD volvió a apoyar al recauchutado PSOE. Tras la muerte de Franco, éste se convertiría en una fuerte contraoferta a la Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD) del presidente de gobierno Adolfo Suárez, que había ganado las primeras elecciones libres en diciembre de 1977. La estrecha amistad entre Felipe González y Willy Brandt, que de joven había participado en la Guerra Civil española como corresponsal de guerra, fortaleció al PSOE. La cooperación entre el SPD y el PSOE en forma de programas de enseñanza y apoyo financiero permitió construir estructuras de partido a nivel local y estatal. El centro de coordinación más importante fue la oficina de Madrid de la Fundación Friedrich Ebert (FES), inaugurada en 1976 bajo la dirección de Dieter Koniecki. Tras los decepcionantes resultados de los socialistas en las elecciones de 1979, el PSOE obtuvo la mayoría absoluta tres años después.

El año 1982 marcó un cambio en el equilibrio de poder del socialismo hispano-alemán. Mientras los socialistas triunfaban en España y Felipe González era elegido presidente del gobierno, en Alemania se quebró la coalición social-liberal del canciller Helmut Schmidt. La relación amistosa entre González y su nuevo homólogo alemán, Helmut Kohl, de la Unión Demócrata Cristiana (CDU), debilitó la posición del SPD en España. Cuando en 1984 surgieron sospechas de que la FES había canalizado fondos de la corporación Flick hacia el gobierno del PSOE en España para favores políticos, éste se vio obligado a distanciarse del SPD. No obstante, los socialistas españoles siguieron con gran atención la labor de oposición de los camaradas alemanes – por ejemplo, el borrador de Irsee para la elaboración de un nuevo programa básico del SPD en 1986. Tras la reunificación alemana, los socialistas españoles se mantuvieron fieles a su línea moderada, que había sido moldeada por el SPD. Así el PSOE rechazó cualquier avance de los sucesores del partido comunista estatal de Alemania Oriental, el Partido del Socialismo Democrático (PDS).