Bilateral Cooperation between Germany and Spain

In terms of Spain’s EEC or NATO membership, Germany presented itself as an honest broker for Madrid’s interests and a door-opener to Europe in the 1980s. In addition to common interests at bilateral and European levels, collaboration also focused on the politics of memory at local level.

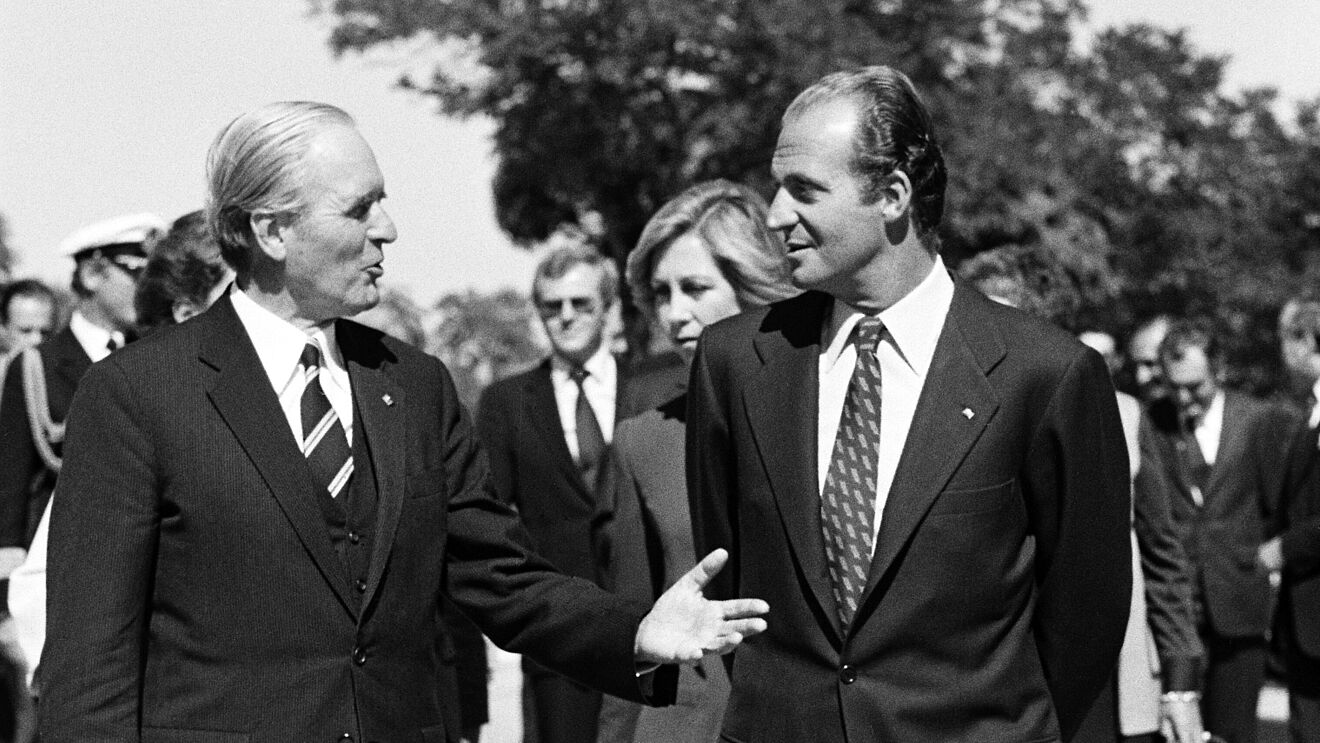

"2022 is a kind of German-Spanish year," noted German Chancellor Olaf Scholz at the joint governmental consultations in A Coruña, Galicia, in October 2022. Two months earlier, his counterpart Pedro Sánchez had already been a guest at the German cabinet retreat in Merseburg. The joint governmental consultations between both countries date back to the 1980s. While there had already been annual meetings between German Foreign Minister Walter Scheel and his Spanish counterparts between 1970 and 1973, the informal state visit by German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt at the turn of the year 1976/77, which he combined with a private family vacation in Marbella, represented a breakthrough. In 1977, both King Juan Carlos and Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez would reciprocate the visit. During the inaugural visit of his Socialist successor Felipe González to the German capital in 1983, Spanish Foreign Minister Fernando Morán initiated continuous governmental consultations, which were held annually from 1984 onward; in 1986 in Madrid, 1987 in Bonn, 1989 in Seville and 1990 in Constance.

There was much to talk about. While the German embassy in Spain kept the German Foreign Office informed about the most important political developments of the transition period, they were concerned about the increasing political violence. Terrorist attacks by ETA at the tourist sites of Marbella, Benidorm and Torremolinos, as well as extortion attempts by a Canarian separatist guerrilla against the German tourist agencies TUI and Neckermann, also touched upon German interests. At the European level, Bonn advocated Spain's admission to the EEC, which Madrid had applied for in 1977 and which finally took place at the turn of the year 1985/86. Spain, on the other hand, was skeptical about NATO, partly because of divergent positions on the Middle East, Latin American policy, and the Gibraltar issue. While German President Karl Carstens’ promotional visit to Madrid in 1981 paved the way for Spain's accession to NATO, the PSOE government, originally hostile the military alliance, changed its stance in 1985, also at the instigation of the Federal Republic. In 1988, Spain's reluctance to participate in the European joint project, the "Jäger 90" fighter aircraft, caused political rifts between Bonn and Madrid.

At the local level, a lively exchange between Germany and Spain took place, especially in the 1980s, and in terms of commemorative politics. Numerous town twinning agreements were concluded, for example between the university cities of Würzburg and Salamanca (1980), the heavy industry centers Duisburg and Bilbao (1985) and the historic imperial residence cities Aachen and Toledo (1985). The partnership between Pforzheim and Guernica (1989) was particularly symbolic, as both cities had been devastated by large-scale aerial bombardments. Ambassador Henning Wegener apologized on behalf of German President Roman Herzog for the Legion Condor’s bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War on April 26, 1997, the 60th anniversary of the Basque town’s destruction. While German Ambassador Lothar Lahn ‘s initiative to propose King Juan Carlos for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980 failed, the monarch was awarded the Charlemagne Prize for "Unity and Human Dignity" by the city of Aachen in 1982. Three years later, German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher received an honorary doctorate from the University of Salamanca.

Bilateral Cooperation between Germany and Portugal

In the logic of the Cold War, the Federal Republic of Germany maintained a good relationship with its NATO ally Portugal, despite it being a dictatorial regime. At the same time, however, the FRG also supported the emergence of democracy in Portugal.

The “best-governed state in Europe” – this is how the Portuguese dictatorship was described by the right-wing intellectual Emil Franzel in 1952. Although this was by no means a majority opinion in the early Federal Republic of Germany, it nevertheless points to the flaw that Germany rarely maintained the necessary critical distance to its dictatorial partner in Portugal. Particularly controversial was the support of the Portuguese Colonial Wars via deliveries of arms, which were only reduced in scope in the mid-1960s due to international pressure. The initial course taken by the CDU and CSU in bilateral relations hardly ever changed, even with the replacement of the CDU by the social-liberal coalition in 1969 under Willy Brandt. The officials in Bonn were optimistic that the liberalisation of the “New State” would come about as soon as Marcello Caetano took office. In order not to endanger the good bilateral relations between the two nations, the Foreign Office refrained from officially supporting opposition forces, as this would have comprised the regime. Instead, in the style of the “Neue Ostpolitik” and with Egon Bahr’s concept of “change through rapprochement”, the Foreign Office tried to persuade the reformist and Europe-oriented forces in Portugal to initiate a regime change.

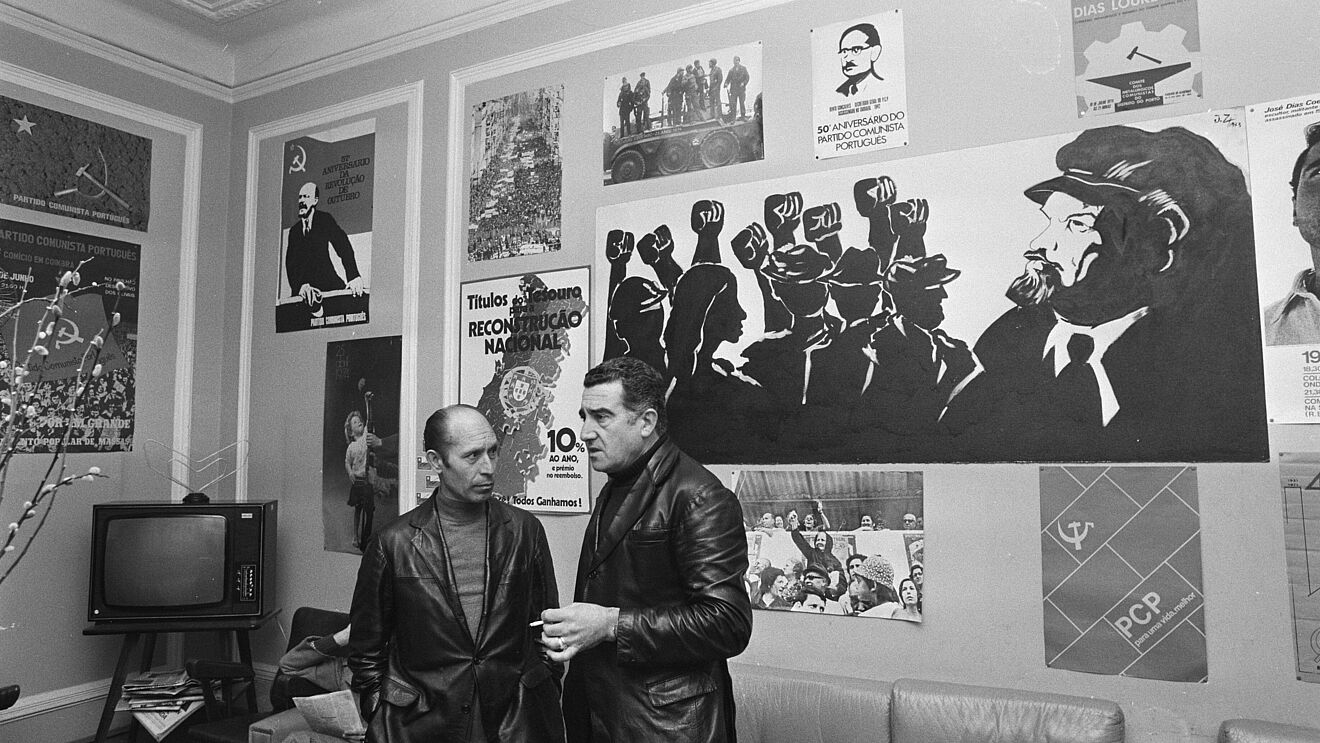

Against all expectations, the Portuguese dictatorship was overthrown before the neighbouring Franco regime. News of the events of April 1974 was greeted with joy in the Foreign Office. Soon, however, this great enthusiasm gave way to even greater concern. In the early power struggle which raged in revolutionary Portugal, the moderate political forces (PS and PPD) were clearly outnumbered by the communist ones. Consequently, the efforts of the Foreign Office and the Chancellery focused primarily on mobilising European social democracy in support of the moderate parties. Likewise, requests for economic aid were met, but only on the condition that free elections would be held in Portugal in March or April 1975. In retrospect, this was a courageous move on the part of the German government, since US foreign policy under Kissinger already considered the Portuguese transition a failure due to communist dominance and was thus discussing the expulsion of Portugal from NATO. In 1976, Schmidt could consequently claim with self-confidence that, in this chapter of world politics, even the Americans had followed German advice.

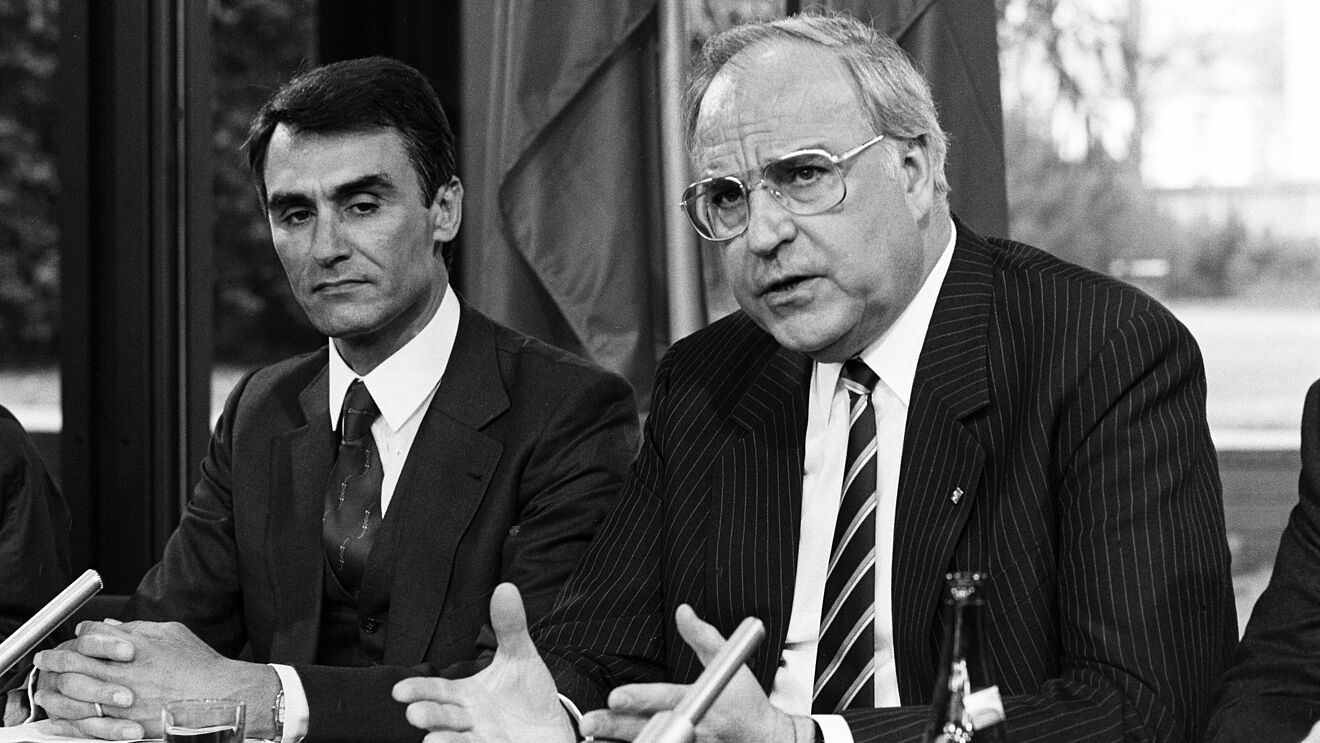

After the election of the first constitutional government in April 1976, bilateral relations between Portugal and the Federal Republic can be divided into three main lines. First, both the young Portuguese democracy and the Federal Republic were keen to quickly integrate Portugal into the EC. Although the process was marked by hitches, the extremely positive bilateral relationship between Germany and Portugal must be emphasised as a factor conducive to EC accession. Secondly, the economic relationship between the two countries deepened. However, the economic aid already mentioned was also flanked by incentives for German investment, from which sustainable cooperation developed. Thirdly, the development of democratic structures in Portugal remained an important pillar of bilateral relations, which were also largely provided by party-affiliated foundations. Finally, the successful integration of 100,000 Portuguese guest workers within Germany was acknowledged in bilateral talks under the Kohl government.