Die technokratische Militärdiktatur in Brasilien (1964-1985)

Ganze 21 Jahre (1964-1985) herrschten die Militärs über Brasilien. Im Kontext des Kalten Krieges gingen sie mit äußerster Brutalität insbesondere gegen die kommunistische Opposition vor. Im Klima der „Ordnung“ sollte dann eine technokratische Elite die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung des Landes sicherstellen.

Am 31. März 1964 schloss sich in Brasilien eine große Koalition der Rechten aus konservativ-kirchlichen Kreisen, der Wirtschaftselite, führender Militärs, einiger Gouverneure und des Botschafters der USA zusammen, um die sozialistischen „Basisreformen“ des damaligen Präsidenten João Goulart zu unterbinden und ihn des Amtes zu entheben. Die Militärs gaben in der Nachfolge nicht die Macht zurück, sondern konsolidierten vielmehr ihre Position innerhalb der bestehenden Verfassungsordnung durch sogenannte Institutionelle Akte, wodurch sie nach eigenem Gutdünken die Verfassung ergänzen oder außer Kraft setzen konnten. Bis Oktober 1969 waren auf den ersten Institutionellen Akt 16 weitere gefolgt. Staatsoberhaupt waren über 21 Jahre hinweg fünf Vier-Sterne-Generale, die in zwei ideologische Hauptlinien aufgeteilt werden können: einerseits die „moderate Linie“ – auch Grupo Sorbonne oder Castelistas genannt – unter Humberto Castelo Branco (1964-1967), Ernesto Geisel (1974-1979) und João Baptisto de Oliveira Figueiredo (1979-1985). Anderseits die „harte Linie“ unter Artur da Costa e Silva (1967-1969) und Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969-1974).

Auf die Etablierung der Militärdiktatur folgte die Eliminierung der politischen Opposition auf dem Fuße. Tausende Politiker und Beamte verloren in der „Operation Säuberung“ ihre politischen Rechte. Im Namen der ersten ideologischen Säule des Regimes, der „nationalen Sicherheitsdoktrin“, wurde der Repressionsapparat rasch aufgebaut, als dessen Speerspitze der Nachrichten- und Sicherheitsdienst SNI fungierte. Sowohl die erste ideologische Säule des Regimes als auch die zweite Säule der „wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung“ wurden ab Oktober 1967 unter dem Hardliner Artur da Costa e Silva stärker forciert. Mit Hilfe des Einsatzes von Technokraten in der Wirtschaftspolitik gelang dem Regime zwischen 1968 und 1973 das „brasilianische Wirtschaftswunder“. Im Windschatten dieser Entwicklung konnten die Hardliner insbesondere unter Präsident Emílio Garrastazu Médici die Repression erheblich anziehen: Politische Gegner wurden verfolgt, gefoltert und in über 400 Fällen auch ermordet. Für eine politische Wende sorgte ab 1974 die Präsidentschaft Ernesto Geisels, der eine kontrollierte Öffnung des Regimes betrieb.

Am 15. März 1979 übernahm João Baptista de Oliveira Figueiredo, der ehemalige Chef des SNI und bevorzugter Kandidat der moderaten Linie, das Präsidentenamt. Er sollte die Macht an einen zivilen Präsidenten übergeben. Als einer der erste Schritte zur Demokratisierung galt die Rückkehr vom Zwei- zum Mehrparteiensystem. In diese Zeit fällt auch das Amnestiegesetz vom 28. August 1979. Ursprünglich als Konzession an die linke Opposition gedacht, gewährte es nicht nur eine Amnestierung oppositioneller Straftaten, sondern dekretierte ebenso die Strafffreiheit aller Verbrechen der Militärdiktatur. Den Rückhalt der Bevölkerung verlor das Regime schließlich durch das Scheitern der Wirtschaftspolitik und die fortdauerende Absenz ziviler Freiheiten. Die steigende Unzufriedenheit spitzte sich 1984 in Massendemonstrationen („Direktwahlen jetzt!“) zu. Auch wenn die Militärs die Direktwahlen nicht zuließen, setzte sich im Kongress der Oppositionskandidat Tancredo Neves als Präsidentschaftskandidat durch - er verstarb jedoch bereits vor seinem Amtsantritt. Übergangspräsident wurde 1985 der regimetreue Vize José Sarney. Mit der Verabschiedung der Verfassung von 1988 galt die Transition zur „Neuen Republik“ in Brasilien als abgeschlossen.

La dictadura de Pinochet en Chile (1973–1990) y de la junta militar en Argentina (1976–1983)

Durante la transición democrática española, juntas militares asumieron el poder en Chile y Argentina. Tras crímenes masivos y graves violaciones de los derechos humanos, los militares cedieron el poder en la década de 1980 y se amnistiaron, siguiendo el modelo español.

"Teniendo presente la gravísima crisis social y moral por la que atraviesa el país [y] la incapacidad del gobierno para controlar el caos [...], las fuerzas armadas y carabineros están unidos para iniciar su histórica y responsable misión de luchar por la liberación de la Patria." Con estas palabras, la junta militar dirigida por el Comandante en Jefe Augusto Pinochet legitimaba su golpe contra Salvador Allende, presidente socialista de Chile, el 11 de septiembre de 1973. Tres años antes, Allende había sido elegido con una estrecha mayoría, combatiendo la pobreza del país con nacionalizaciones y una generosa política social, que al mismo tiempo sumió al país en una grave crisis económica por inflación galopante y lo distanció de Estados Unidos. Este último reconoció inmediatamente a Pinochet como presidente legítimo. Tres años más tarde, los militares también tomaron el poder en Argentina. El vacío dejado por la muerte del presidente Juan Domingo Perón, la creciente crisis económica y el aumento de los asesinatos cometidos por la guerrilla urbana de izquierdas Montoneros llevaron a los militares del general Jorge Videla someter bajo arresto domiciliario a la esposa, vicepresidenta y sucesora de Perón, Isabel Martínez de Perón.

Especialmente en los meses inmediatamente posteriores a la toma del poder, los gobiernos militares de Chile y Argentina cometieron crímenes masivos y graves violaciones de los derechos humanos. Pinochet – un ferviente admirador de Franco que fue uno de los pocos invitados de estado presente al acto funerario del dictador español en 1975 – utilizó principalmente a la policía secreta DINA para secuestrar, torturar y ejecutar a miembros de la oposición. En Argentina, el presidente Videla declaró subversivos a todos aquellos que socavaran los valores cristianos del país con "ideas contrarias a nuestra civilización." También en este país se secuestró, torturó y asesinó a disidentes. En Chile, de 30.000 torturados, murieron unos 3.000; en Argentina, desaparecieron entre 6.000 y 30.000 personas. Una cifra exacta se hace difícil por la práctica de las "desapariciones," es decir, secuestros sin certeza sobre el paradero de los detenidos. Mientras Pinochet basaba su legitimidad en una mejora temporal de la situación económica de Chile mediante reformas estructurales monetarias y referendos manipulados, la situación de la junta militar argentina siguió precaria en todo momento debido a la inestable economía del país. Grandes acontecimientos como la organización del Mundial de Fútbol de 1978 apenas pudieron distraer la atención de estos problemas.

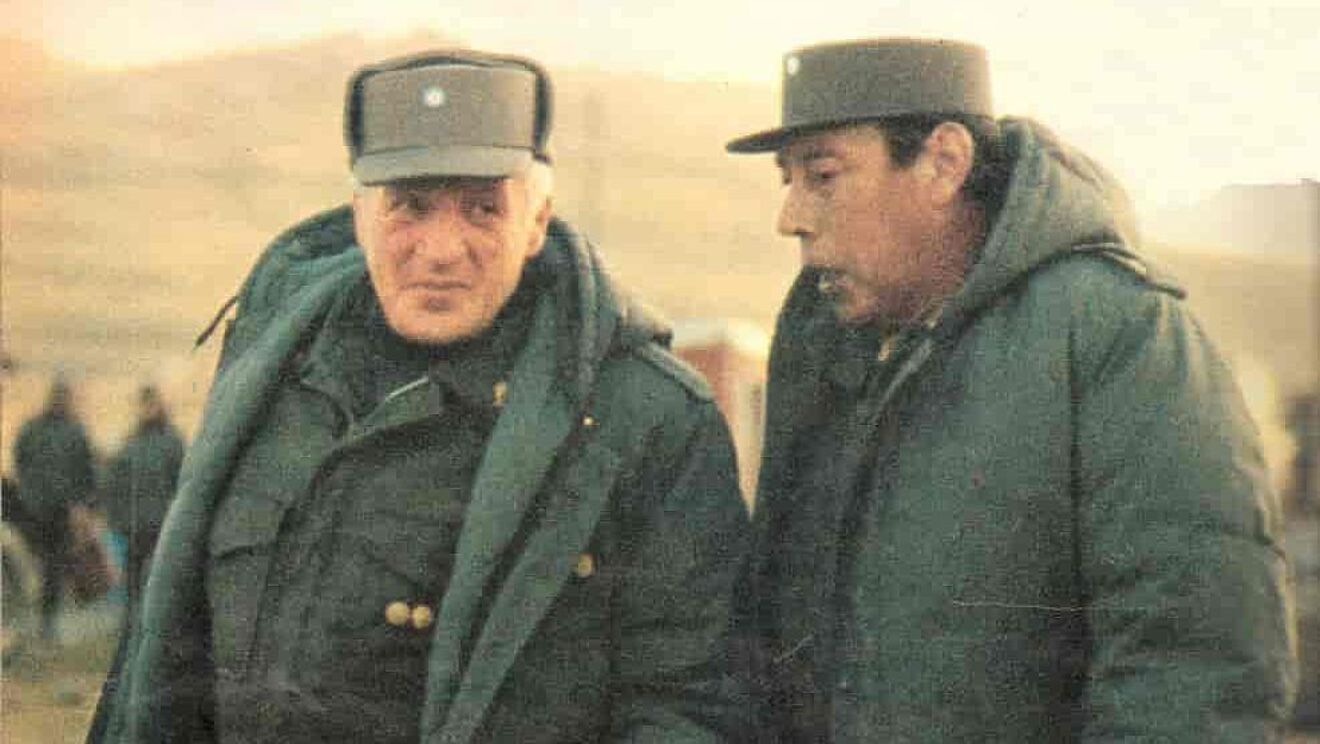

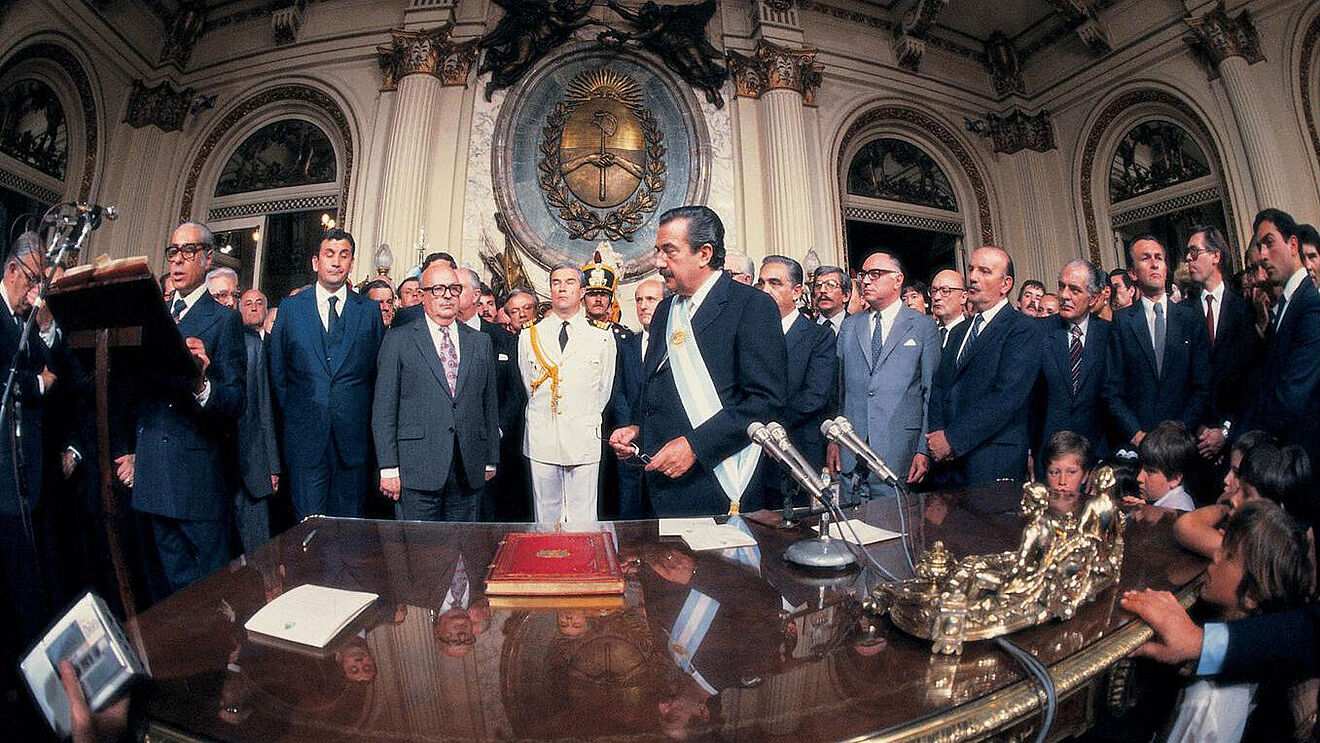

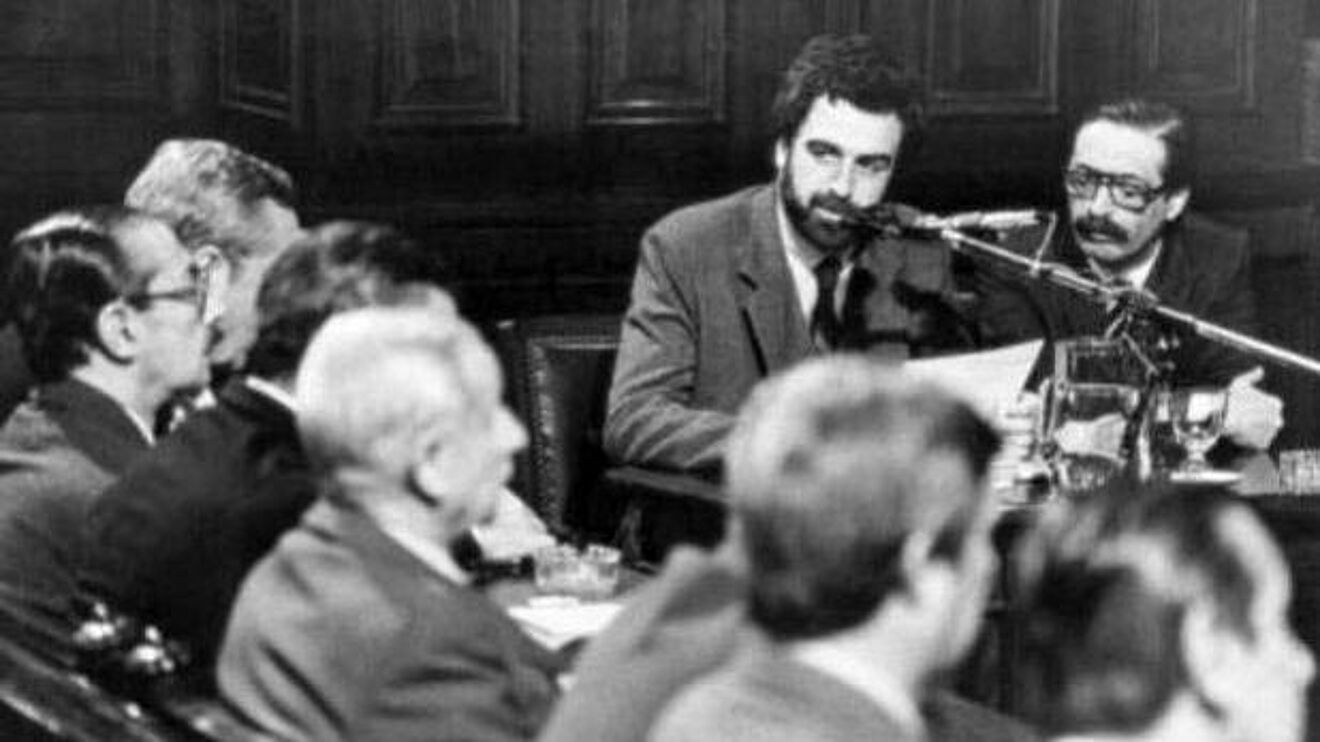

Con la ocupación de las Islas Malvinas frente a la costa argentina – colonia de Gran Bretaña desde 1833 –, el nuevo presidente argentino, el general Leopoldo Galtieri, intentó encender una ola de euforia nacional en 1982. Pero la exitosa contraoperación británica asestó un golpe mortal a la junta militar. En 1983, Reynaldo Bignone, el último presidente militar argentino, convocó elecciones libres. Al mismo tiempo, una ley de amnistía garantizó la impunidad de los antiguos gobernantes. En Chile, el presidente Pinochet intentó legitimarse en 1988 mediante la celebración de otro referéndum, que sorprendentemente perdió. A pesar de las elecciones libres de 1989, Pinochet, que se aseguró los cargos de comandante en jefe del ejército y senador vitalicio, siguió siendo una figura influyente en la política chilena. Aunque dos comisiones de la verdad, en 1991 y 2004, investigaron los crímenes de los años de Pinochet, esto no tuvo consecuencias legales para el ex gobernante, que murió en 2006, ya que una ley de amnistía de 1978 le protegía de ser procesado. La situación fue diferente en Argentina, donde la comisión de la verdad CONADEP presentó un informe de violaciones de los derechos humanos en 1984, en base al cual los responsables de la junta militar – incluidos Videla, Galtieri y Bignone – fueron condenados a largas penas de prisión en 1985.