Relaciones bilaterales entre Alemania y España

En los años ochenta, Alemania se presentó como un intermediario honesto para los intereses de España. Contribuyó al acceso del país ibérico a la CEE y a la OTAN. Además de los intereses comunes a nivel bilateral y europeo, las colaboraciones locales también enfocaron en la memoria.

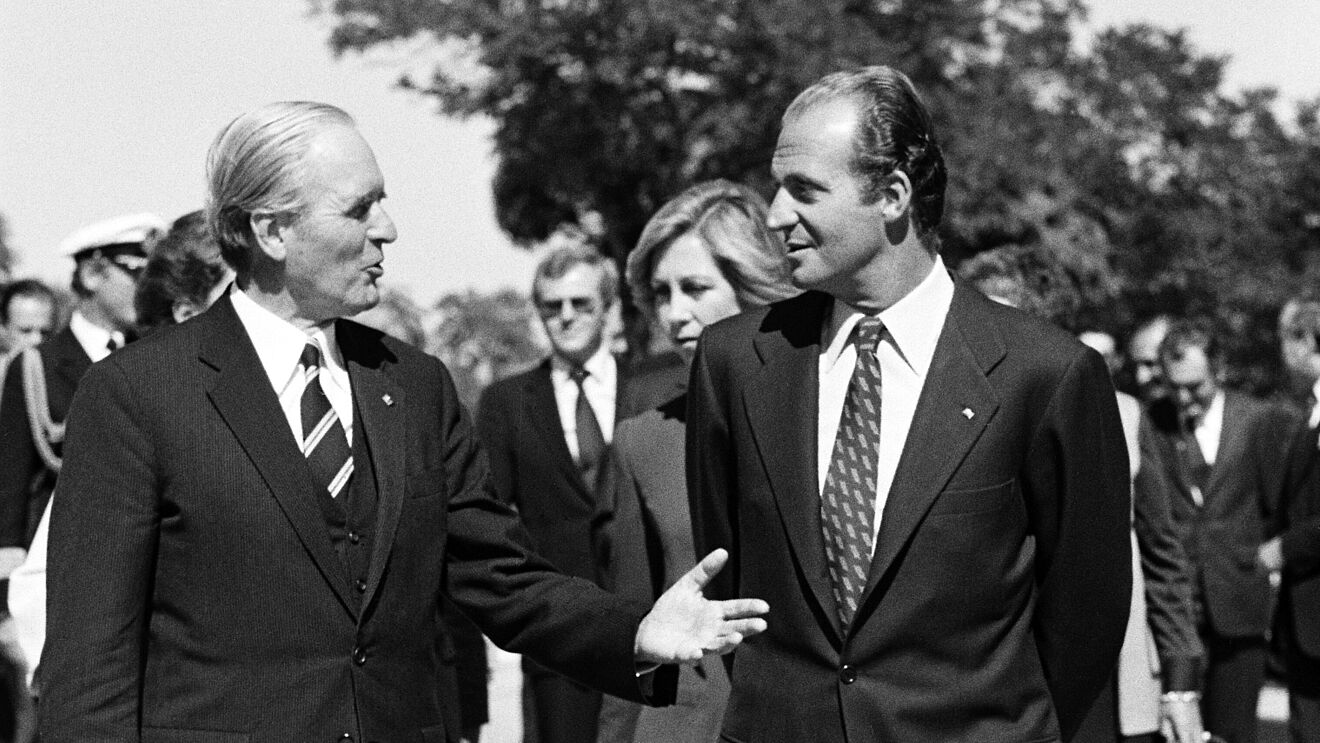

"2022 es, de un cierto modo, un año germano-español," señaló el canciller federal Olaf Scholz en las consultas gubernamentales conjuntas celebradas en A Coruña, Galicia, en octubre de 2022. Dos meses antes, su homólogo Pedro Sánchez ya había sido invitado a la reunión del gabinete alemán en el castillo de Merseburg. Las consultas gubernamentales conjuntas entre ambos países son una tradición que se remonta a los años ochenta. Aunque se habían celebrado reuniones anuales entre el ministro alemán de Asuntos Exteriores, Walter Scheel, y sus homólogos españoles entre 1970 y 1973, la visita de estado informal del canciller alemán Helmut Schmidt a principios del año 1976/77, combinado con unas vacaciones familiares privadas en Marbella, supuso un gran avance. En 1977, tanto el rey Juan Carlos como el presidente del gobierno Adolfo Suárez devolvieron la cortesía. Durante la visita inaugural de su sucesor socialista Felipe González a la capital alemana en 1983, el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores español Fernando Morán propuso consultas gubernamentales continuas, que se celebraron anualmente a partir de 1984: 1986 en Madrid, 1987 en Bonn, 1989 en Sevilla y 1990 en Constanza.

Había mucho que discutir: mientras las misiones diplomáticas alemanes en España mantenían informado al Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores sobre los acontecimientos políticos más importantes de la transición democrática, éste estaba preocupado por la creciente violencia política. Los atentados terroristas de ETA en los bastiones turísticos de Marbella, Benidorm y Torremolinos, así como los intentos de chantaje de una guerrilla separatista canaria contra los operadores turísticos TUI y Neckermann, también afectaron a los intereses alemanes. Al nivel europeo, Bonn hizo campaña a favor de la admisión de España en la CEE, que Madrid había solicitado en 1977 y que se produjo a finales del año 1985/86. Por otro lado, la parte española se mostraba escéptica con respecto a la OTAN, entre otras cosas debido a las posiciones divergentes en la política de Oriente Medio y América Latina, así como en la cuestión de Gibraltar. Durante su visita a Madrid en 1981 el presidente alemán Karl Carstens allanó el camino para la adhesión de España a la OTAN al año siguiente. El gobierno del PSOE, en un principio hostil a la OTAN, cambió su postura en 1985, también a instancias de la República Federal. Sin embargo, la reticencia de España a participar en el proyecto conjunto europeo del avión de combate "Jäger 90" provocó la irritación entre Bonn y Madrid en 1988.

Al nivel local, se produjo un animado intercambio entre Alemania y España en la década de 1980, también en materia de política conmemorativa. Se celebraron numerosos hermanamientos de ciudades, por ejemplo, entre las ciudades universitarias de Wurzburgo y Salamanca (1980), los centros de la industria pesada Duisburgo y Bilbao (1985) y las históricas residencias imperiales de Aquisgrán y Toledo (1985). La asociación entre Pforzheim y Gernika (1989) fue especialmente simbólica, ya que ambas ciudades habían sido bombardeadas casi en su totalidad durante la guerra. El embajador Henning Wegener pidió perdón por el bombardeo de la Legión Cóndor alemana durante la Guerra Civil española el 26 de abril de 1997, el 60º aniversario de la destrucción de Gernika, en nombre del presidente alemán Roman Herzog. Aunque el embajador alemán Lothar Lahn fracasó en 1980 con su iniciativa de proponer al rey Juan Carlos para el Premio Nobel de la Paz, el monarca fue galardonado con el Premio Carlomagno a la "Unidad y Dignidad Humana" por la ciudad de Aquisgrán en 1982. Tres años más tarde, el ministro federal de Asuntos Exteriores, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, fue investido doctor honoris causa por la Universidad de Salamanca.

Bilaterale Zusammenarbeit

zwischen Deutschland und Portugal

In der Logik des Kalten Kriegs pflegte die Bundesrepublik trotz des diktatorischen Charakters ein gutes Verhältnis zum NATO-Bündnispartner Portugal. Gleichermaßen unterstütze die Bundesrepublik aber auch die Demokratiewerdung Portugals.

Der „bestregierte Staat Europas“ – so wurde die portugiesische Diktatur vom rechtskonservativen Emil Franzel 1952 apostrophiert. Es handelt sich hierbei zwar keineswegs um eine mehrheitsfähige Meinung in der frühen bundesrepublikanischen Öffentlichkeit, dennoch weist sie auf den Makel hin, dass man im bilateralen Verhältnis zum autoritären Partner in Portugal selten die nötige kritische Distanz behielt. Besonders umstritten war die Unterstützung der portugiesischen Kolonialkriege mit Waffenlieferungen, die in ihrem Umfang erst zur Mitte der 1960er Jahre auf internationalen Druck reduziert wurden. Der von CDU und CSU eingeschlagene Kurs in den bilateralen Beziehungen änderte sich zunächst auch kaum mit dem Wechsel zur sozialliberalen Koalition 1969 unter Willy Brandt. In Bonn war man optimistisch gestimmt, dass mit dem Antritt Marcello Caetanos die Liberalisierung des „Neuen Staats“ vollzogen werden würde. Um die guten bilateralen Beziehungen nicht zu gefährden, verzichtete man im Auswärtigen Amt darauf, dass Regime durch offizielle Unterstützung oppositioneller Kräfte zu kompromittieren. Vielmehr versuchte man im Stile der „neuen Ostpolitik“ und mit Egon Bahrs Konzept „Wandel durch Annäherung“ die reformerischen und europaorientierten Kräfte in Portugal für sich zu gewinnen.

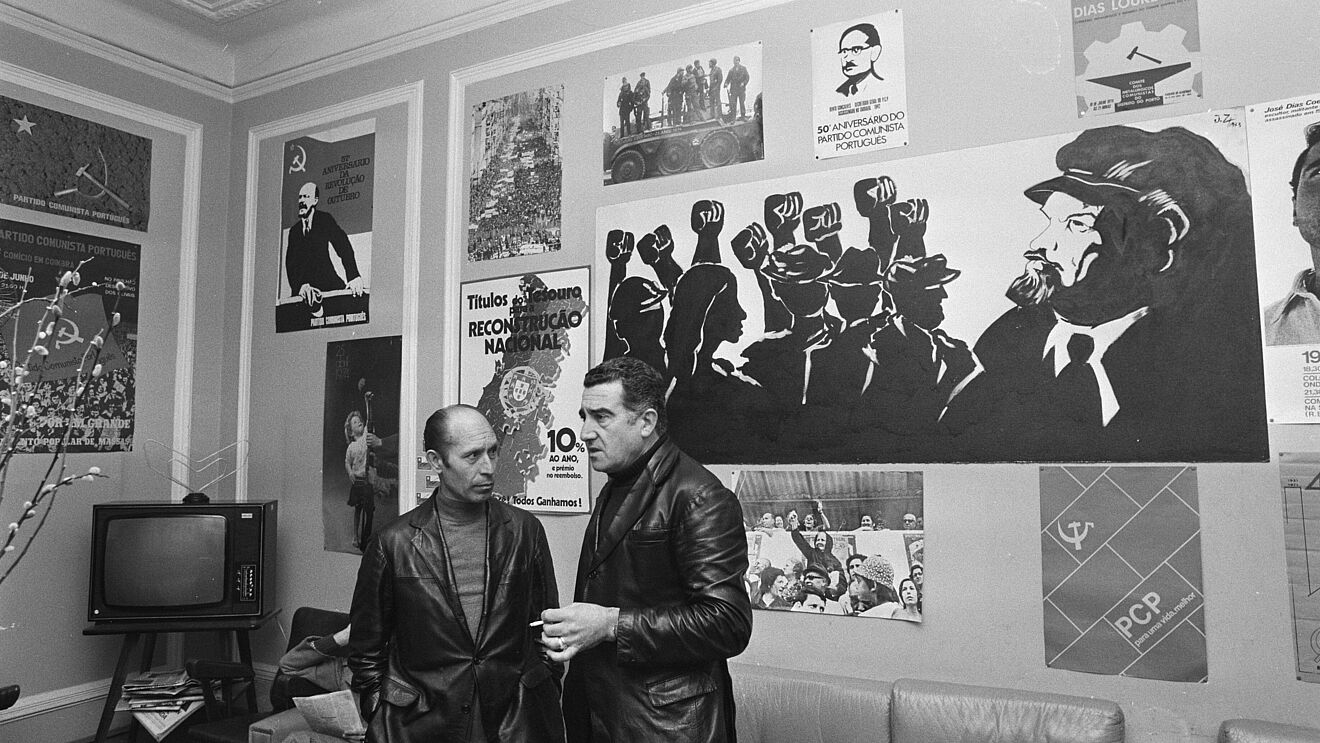

Wider Erwarten wurde die portugiesische Diktatur noch vor dem benachbarten Franco-Regime gestürzt. Die Neuigkeiten über die Aprilereignisse wurden im Auswärtigen Amt freudig aufgenommen. Bald jedoch wich der große Enthusiasmus einer noch größeren Besorgnis: Im frühen Machtkampf des revolutionären Portugals waren die moderaten politische Kräfte (PS und PPD) den kommunistischen klar unterlegen. Die Bemühungen des Auswärtigen Amtes und des Kanzleramtes konzentrierten sich folglich zuvörderst auf die Mobilisierung der europäischen Sozialdemokratie für die gemäßigten Parteien. Ebenso entsprach man den Wünschen nach wirtschaftlicher Hilfe, jedoch nur unter der Bedingung, dass in Portugal freie Wahlen im März oder April 1975 stattfinden würden. In der Retrospektive handelte es sich um ein mutiges Vorgehen der Bundesregierung, da die US-Amerikanische Außenpolitik unter Kissinger die portugiesische Transition aufgrund der kommunistischen Dominanz bereits für gescheitert hielt und über einen Ausschluss Portugals aus der NATO beriet. 1976 konnte Schmidt folglich mit Selbstbewusstsein behaupten, dass in diesem Kapitel der Weltpolitik selbst die Amerikaner dem deutschen Rat gefolgt seien.

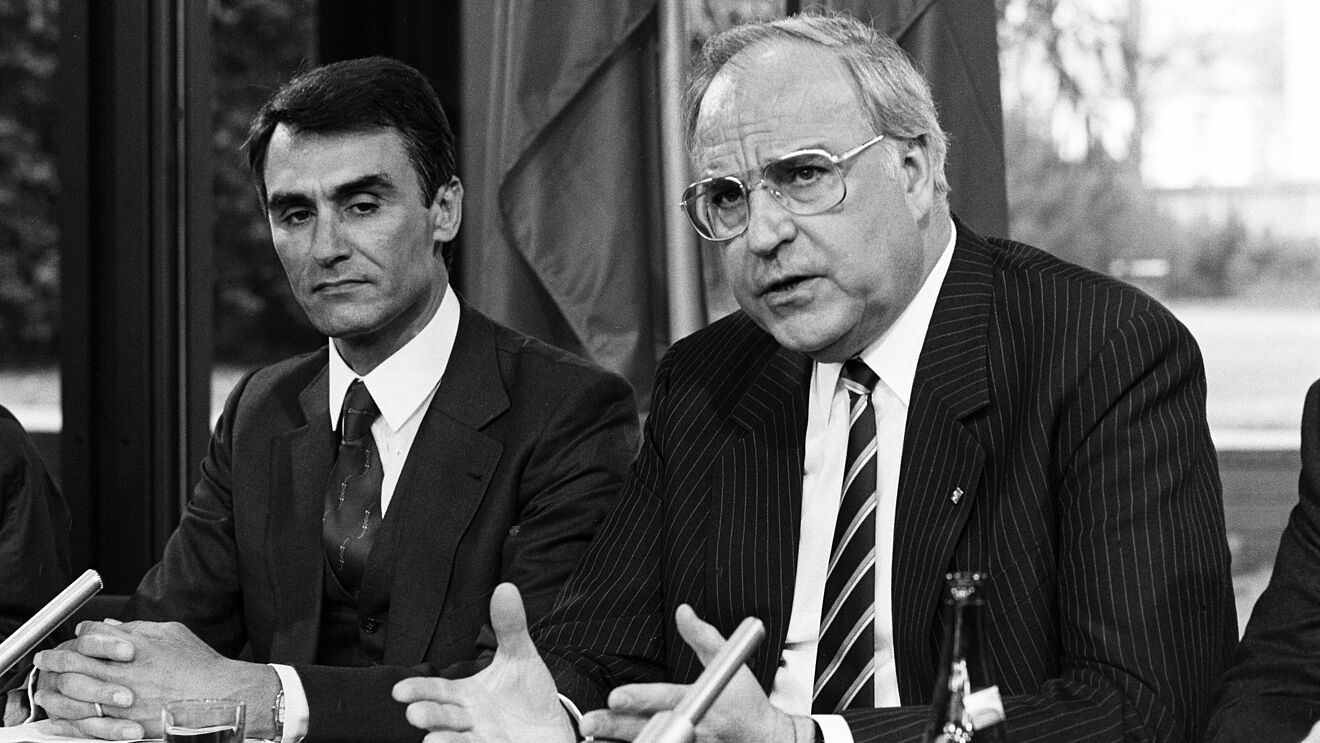

Nach den Wahlen im April 1976 zur ersten konstitutionellen Regierung lassen sich die bilateralen Beziehungen zwischen Portugal und der Bundesrepublik in drei Hauptlinien aufteilen: Erstens war sowohl der jungen portugiesischen Demokratie als auch der Bundesrepublik daran gelegen, Portugal rasch in die EG zu integrieren. Obwohl der Prozess von Peripetien geprägt war, muss man das äußerst positive bilaterale Verhältnis zwischen Deutschland und Portugal als förderlichen Faktor für den EG-Beitritt herausstellen. Zweitens vertiefte sich das wirtschaftliche Verhältnis zwischen den beiden Ländern. Die bereits angesprochene Wirtschaftshilfe wurde aber auch durch Anreize für deutsche Investitionen flankiert, aus denen nachhaltige Kooperationen entstanden. Drittens blieb der Ausbau demokratischer Strukturen in Portugal eine wichtige Säule der bilateralen Beziehungen, die auch zu einem großen Teil durch die Parteienstiftungen erbracht wurden. Von deutscher Seiter wurde schließlich unter der Regierung Kohl die erfolgreiche Integration von 100.000 portugiesischen Gastarbeitern in bilateralen Gesprächen gewürdigt.