Statuen und Topographie in Portugal

Auch Demokratien verewigen ihre Helden in Statuen und Monumenten. Diese Aussage trifft zunehmend für Portugal zu. Das diktatorische Erbe ist durch seine Widersacher und die Symbole der Nelkenrevolution ersetzt worden. Kontrovers bleibt die Glorifizierung des kolonialen Erbes.

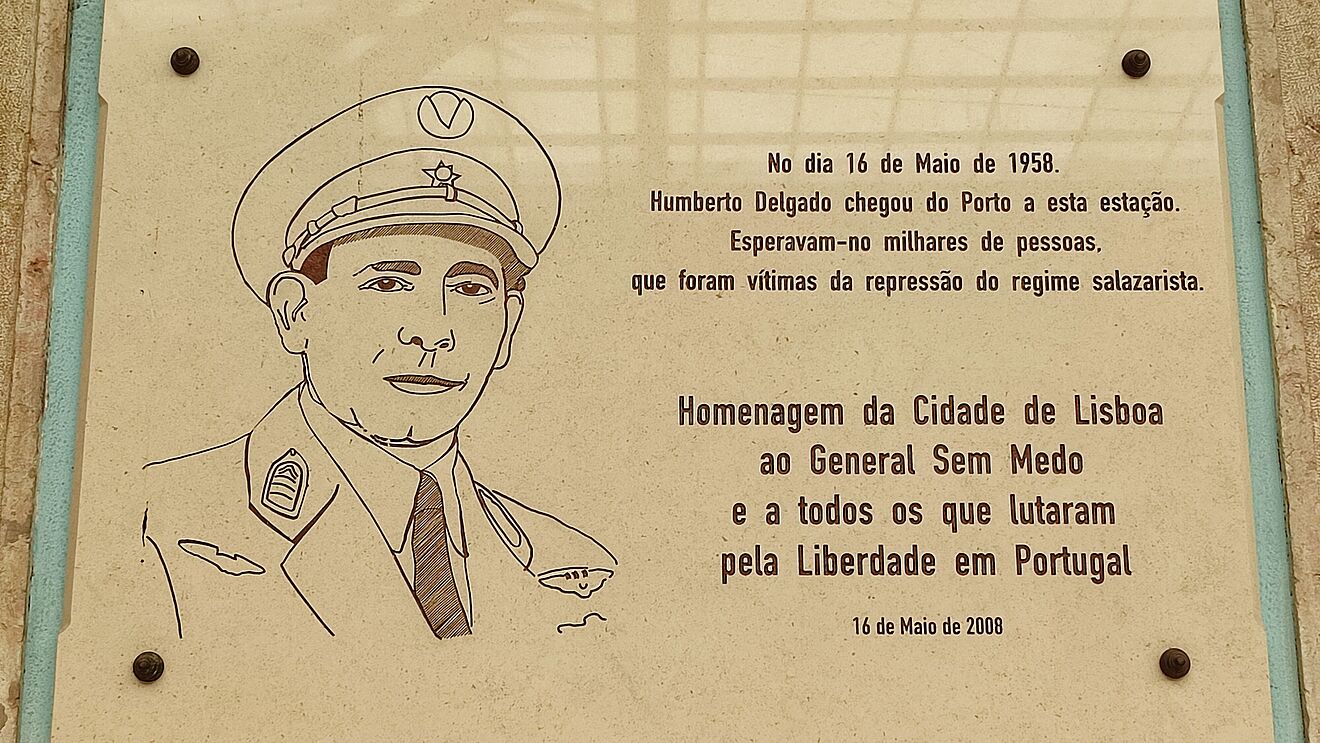

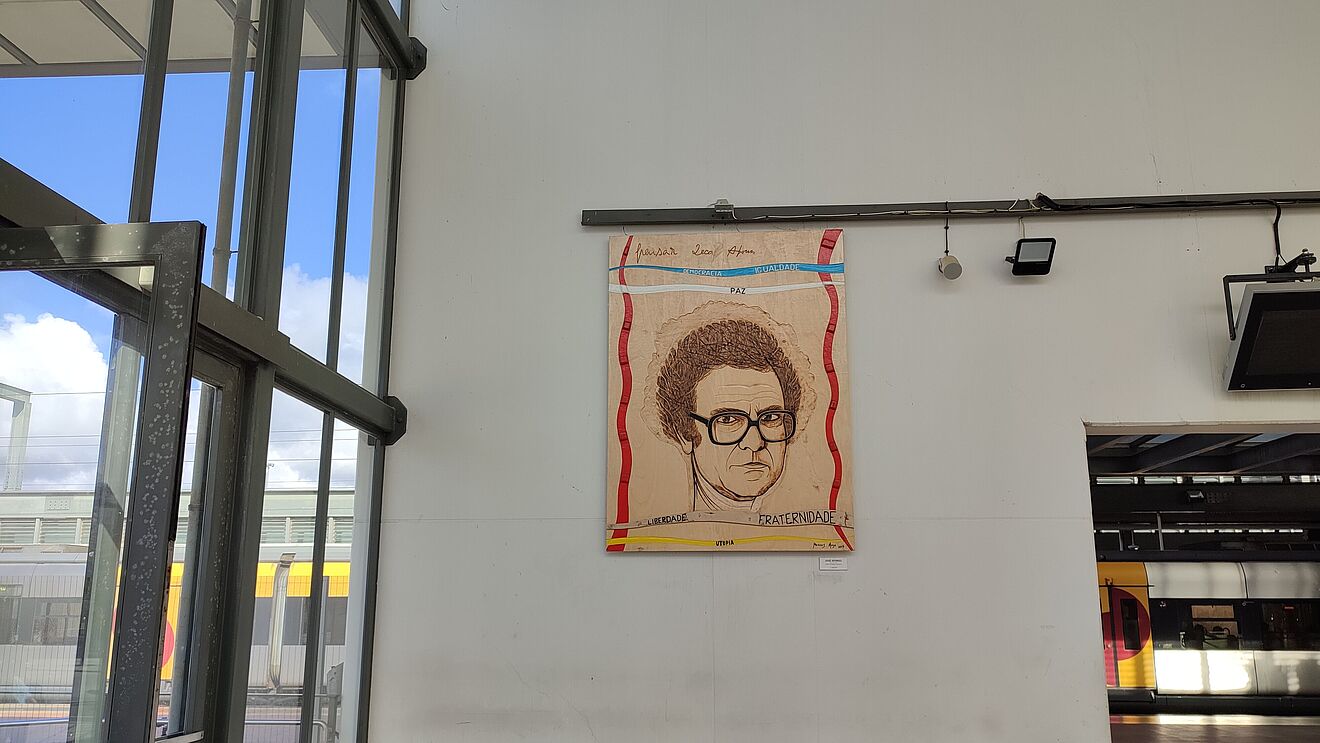

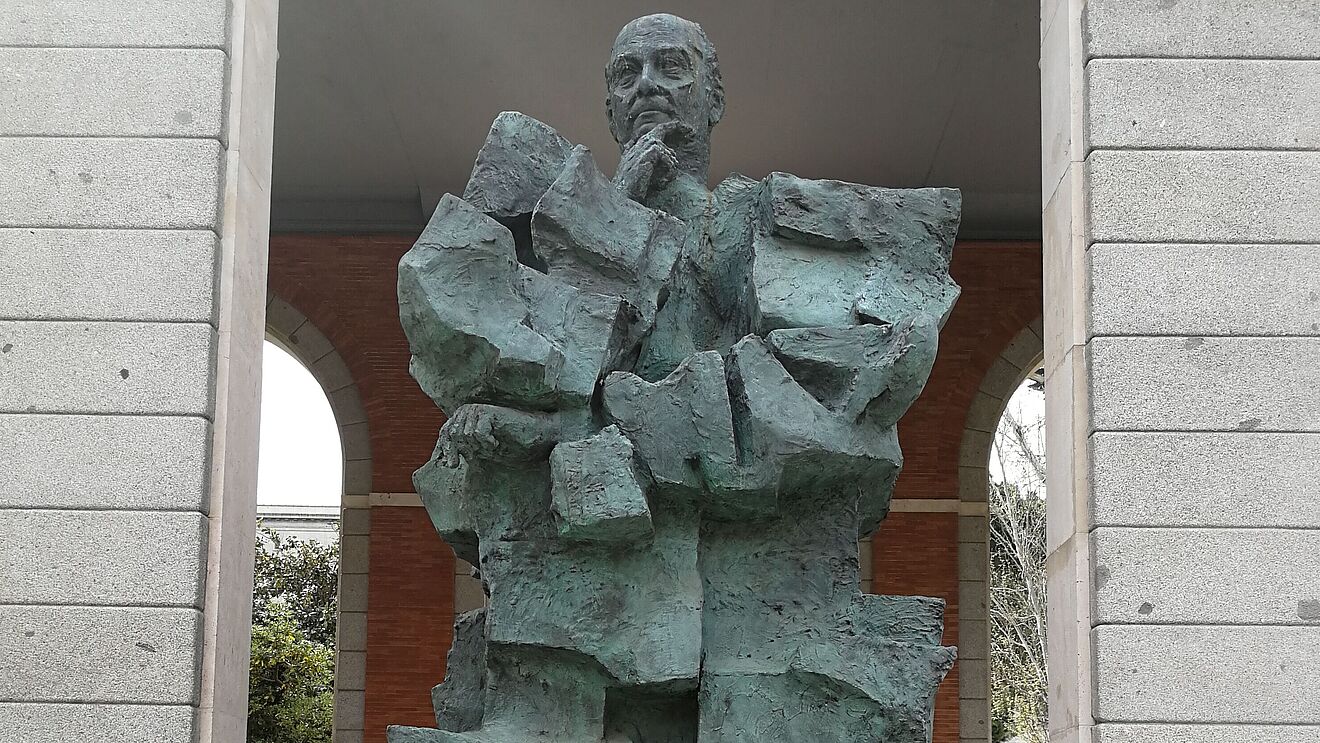

Die Helden des demokratischen Portugals sind heute vor allem jene, die gegen die Diktatur des „Neuen Staats“ opponierten. Die herausragendste Gestalt des militärischen Widerstands war sicherlich der im Volksmund bekannte „General ohne Furcht“ (general sem medo), Humberto Delgado. In den Präsidentschaftswahlen von 1958 sorgte er für eine ernsthafte Krise des Regimes. Seine Kandidatur konnte nur durch Wahlmanipulation gestoppt werden. In Delgados Geburtshaus im kleinen Dorf Boquilobo wurde ihm zu Ehren eine Museumsausstellung eingerichtet und daneben eine Statue errichtet. Die Hauptstraße, die durch das Dorf führt, sowie der Flughafen von Lissabon tragen heute seinen Namen. Im Nachgang des bereits angesprochenen Präsidentschaftswahlkampf 1958 richtete der damalige Bischof von Porto, António Ferreira Gomes, eine Kritik an Salazar – er bezahlte seinen Widerstand mit dem Exil. In Porto wurde auch ihm vor dem imposanten Turm der Kleriker eine Statue von Arlindo Rocha im Jahr 1979 errichtet. Ein prominentes Monument der Würdigung oppositioneller Schriftsteller wie José Saramago und Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen wurde 2001 in Coimbra – unweit vom ehemaligen PIDE-Hauptquartier – eingeweiht.

Kein historisches Ereignis hat die Topographie der portugiesischen Städte in den letzten Jahrzehnten so nachhaltig geprägt wie die Nelkenrevolution vom 25. April 1974. Die erinnerungskulturellen Bezüge fallen dabei vielseitig aus: Zum einen die schon seit der Revolution bekannten Graffiti, die mit ihrer typisch sozialistisch-revolutionären Ikonographie langstreckig Betonmauern in Lissabon verzieren. Zu den beliebten Motiven zählen die rote Nelke, die Zahl 25 oder Hauptmann Salgueiro Maia, der Pars pro Toto für die Bewegung der Streitkräfte steht. Zum anderen gibt es zahlreiche Statuen und Monumente mit vergleichbarer Ikonographie zum Gedenken an den 25. April, die zumeist an den Jahrestagen der Revolution eingeweiht wurden. Abschließend ist auf die erhebliche Wirkung zu verweisen, die der 25. April auf die Toponymie der Großstädte gezeitigt hat. Nicht nur Straßennamen weisen klare Bezüge auf die Aprilereignisse auf, sondern auch große Bauten wie die Hängebrücke über den Tejo in Lissabon, die von ihrem ursprünglichen Namen Salazar-Brücke zu Brücke des 25. April umbenannt wurde.

Im Zuge des revolutionären Umbruchs in Portugal ging man rasch daran, die Überreste der vormaligen Diktatur aus der Topographie des Landes zu entfernen. In erster Linie betraf dies die Statuen und Monumente des Diktators Salazar selbst. Besondere Beachtung verdient die 1965 von Leopoldo de Almeida gegossene Statue in Salazars Heimatgemeinde Santa Comba Dão. Umgehend nach der Revolution wurde sie beschmiert, zeitweise mit schwarzen Decken eingehüllt, bis sie im November 1975 schließlich geköpft wurde. Beim Versuch den Kopf wieder aufzusetzen, kam es zu massiven Unruhen, die sogar ein Todesopfer einforderten. Im Februar 1978 wurde die Statue gesprengt. Ersetzt wurden die Überreste 2010 durch ein Monument für die „Kämpfer in Übersee“ im Portugiesischen Kolonialkrieg – und damit erneut durch eine hochsensible Erinnerung, die zunehmend in die Kritik gerät.

Links

Estatuas y topografía en España

Incluso en la España democrática posterior a 1975, las estatuas del dictador Francisco Franco y sus generales militares permanecieron en sus pedestales. Sólo después del cambio de milenio comenzó en España la era del derribo de monumentos.

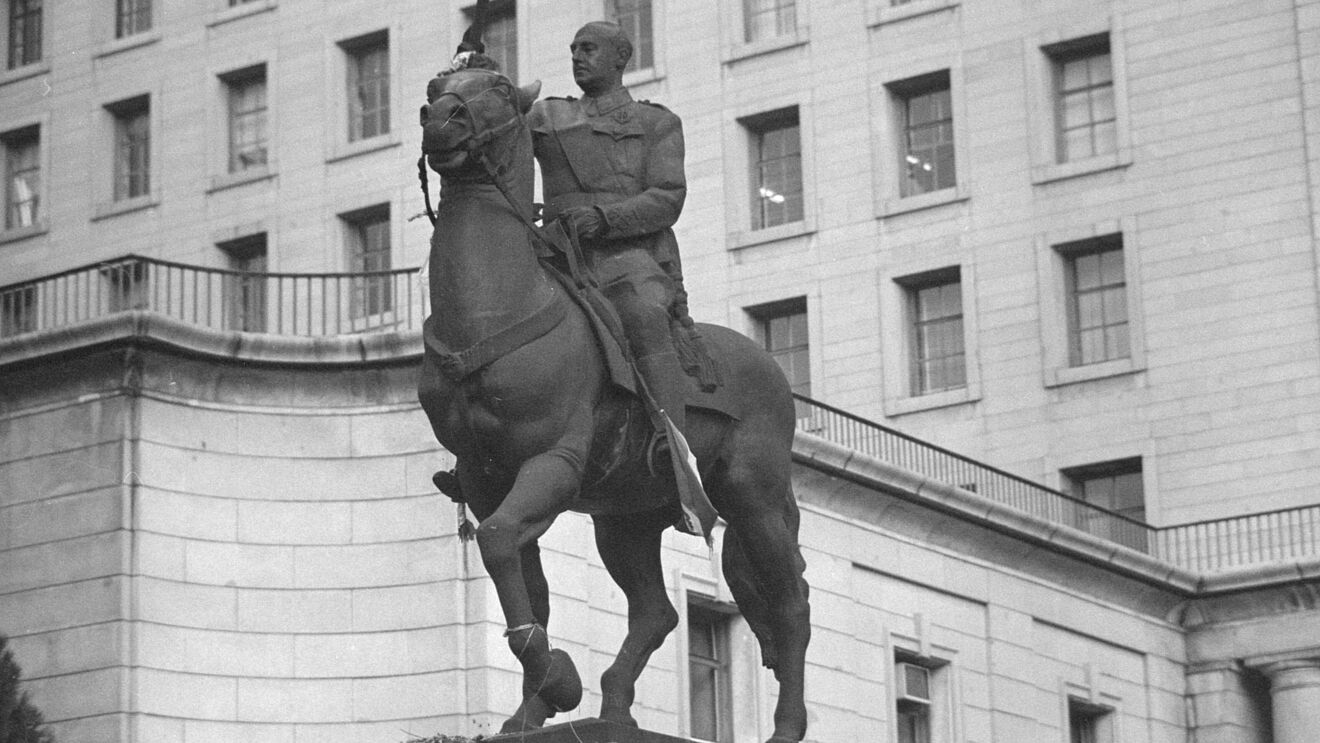

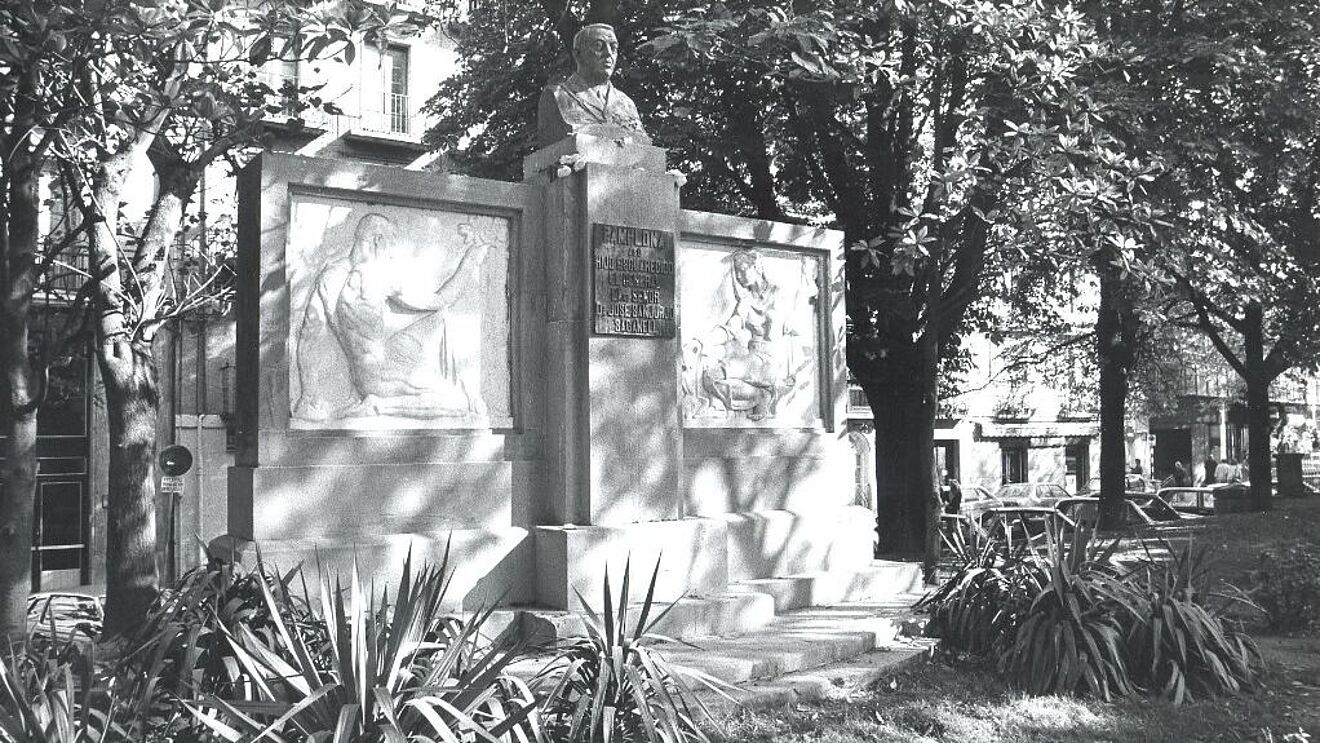

Una cesura que duró 11 horas enteras. Aunque planeada como operación nocturna, los activistas de izquierdas enmascarados tardaron hasta el mediodía del 10 de septiembre de 1983 en levantar la estatua ecuestre del dictador Francisco Franco de su pedestal en la Plaza del Ayuntamiento de Valencia con la ayuda de una grúa. La retirada a instancias del ayuntamiento, acompañada de protestas por ardientes partidarios de Franco, marcó un punto de inflexión. Durante mucho tiempo, el pasado de la dictadura franquista dominó el paisaje urbano, incluso en la España democrática. Las estatuas ecuestres del dictador, erigidas principalmente en los años sesenta, adornaban las plazas centrales de Madrid, Valencia, Santander, Barcelona y Zaragoza. Al mismo tiempo, los monumentos a los generales y militares nacionalistas que habían planeado el golpe se erigieron en sus respectivas ciudades de origen, y permanecieron allí mucho tiempo después de la transición democrática.

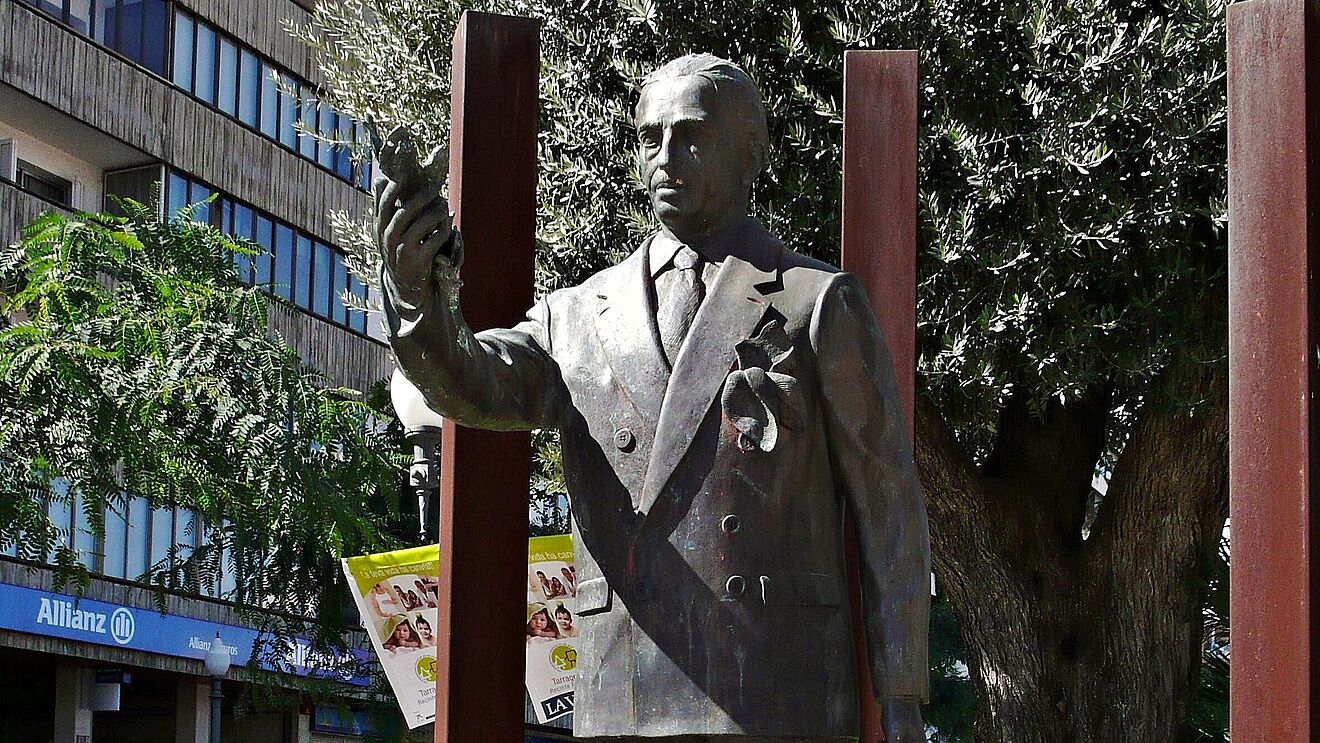

En oposición a estas continuidades, el gobierno PSOE de Felipe González (1982–1996) ya trabajaba a mediados de los ochenta en la construcción de una decidida contramemoria en forma de nuevas estatuas. Así, se erigieron cuatro monumentos en el área metropolitana de Madrid representando a líderes políticos de la Segunda República: los ministros socialistas Indalecio Prieto y Francisco Largo Caballero, el presidente del parlamento Julián Besteiro y el presidente de la República Manuel Azaña, de Izquierda Republicana. Los renombrados escultores españoles Pablo Serrano Aguilar y José Noja Ortega, que habían pasado largos periodos de la dictadura franquista en el exilio americano y regresaron a su patria tras la muerte del dictador, fueron los responsables del aspecto brutalista de las estatuas. Además, el último presidente del gobierno regional catalán, Lluis Companys, ejecutado por los nacionalistas franquistas en 1940, fue honrado con un mausoleo en Barcelona en 1985.

Con el cambio de milenio se inició una importante oleada de demoliciones de monumentos, principalmente como consecuencia de la Ley de Memoria Histórica de 2007. Así, las estatuas ecuestres franquistas de Madrid, Zaragoza, Barcelona y Santander fueron desmanteladas entre 2005 y 2008. Los monumentos franquistas de la periferia española permanecieron. Una estatua en el exclave español de Melilla en Marruecos, que representa al combatiente africano Franco con uniforme colonial, no se retiró definitivamente hasta principios de 2021. La estatua de Franco en Santa Cruz de Tenerife, sigue en pie. Muestra al longevo dictador con los rasgos faciales embellecidos, espada y capa, entronizado sobre un ángel de la victoria. En 2010, el ayuntamiento, dominado por fuerzas conservadores, rebautizó la estatua con el nombre de "Monumento al Ángel Caído" para protegerla de su inminente desmantelamiento.

Enlaces

Video del desmontaje de la estatua ecuestre de Franceo en Valencia, 1983 (español)

Estatuas de Francisco Largo Caballero y Indalecio Prieto en Madrid (Google Streetview)

Estatua de Manuel Azaña en Alcalá de Henares (Google Streetview)

„Monumento al Ángel Caído” en Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Google Streetview)

La hispanista Aleksandra Hadzelek sobre el desmontaje de las estatuas de Franco (inglés)